In an old, Soviet-era joke, a resident tells his apartment building manager, “Voice of America just reported that the roof of our building has been leaking for the last year.” To which the manager answers, “Yeah, the same old U.S. lies and slander.”

Nowadays, that same manager would probably say that such reports are an attempt by the treacherous U.S. to contain Russia, now that it has risen from its knees during President Vladimir Putin’s 15 years in power. In a recent meeting with representatives of the Public Council for the Preparation of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Putin gave his own, peculiar interpretation of the theory of deterrence. “A theory took shape in Cold War times: It was called the deterrence theory,” Putin said. “This theory and its policies were aimed at hindering the development of the Soviet Union. Unfortunately, now we are seeing the same thing. The remains of this outdated deterrence theory are still alive and well [in the U.S.]. Whenever Russia demonstrates positive development and when it shows itself to be a new, strong player and a new source of competition, this is bound to cause concern [in the U.S.] in terms of its economic, political and security interests.”

But the traditional interpretation of deterrence has always carried a primarily military connotation — namely, deterring a potential aggressor from using nuclear weapons against the other side. Nobody doubts that this question was urgent during the Cold War, when the possibility of a military confrontation was real and serious.

The first was the attempt to stop the spread of Soviet influence throughout the world, leading to bloody wars in Vietnam, Nicaragua, Afghanistan and many other places.

The second and most important thrust of deterrence was the desire to prevent the Soviet Union from launching an attack. U.S. theorists argued that an attack could be deterred if the potential aggressor knew that the other side was capable of inflicting unacceptable damage on his own country. The main deterrence theorist of the 1950s was the professor and future U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. He believed that to deter a potential aggressor, a country must possess the guaranteed ability to destroy, even after sustaining a first strike, one-fourth of the aggressor country’s population and one-half of its economic potential.

But only Russia tries to use nuclear deterrence to project its foreign policy agenda. In particular, Moscow points to concerns that the U.S. will gain the ability to launch a first strike with impunity if it deploys a global missile defense system. But the U.S. has for decades stated officially that even a single nuclear warhead breaking through defenses and detonating on its territory would be unacceptable, a fact that eliminates any chance of Washington attacking Russia. No missile defense system could ever guarantee to protect 100 percent against a Russian nuclear missile from breaking through and striking U.S. territory.

In reality, the theory of deterrence lost its relevance with the end of the Cold War and the advent of globalization. How could Russia strike the U.S. when a major portion of its foreign exchange reserves are held in U.S. government securities, when the children of top officials study in U.S. universities and their families live in U.S. cities?

Still, this parody of nuclear deterrence remains an essential element of Russia’s foreign policy because nuclear parity with the U.S. offers comforting proof that Russia is capable of destroying the most powerful country in the world. For the Kremlin, that fact alone automatically makes Russia a major player on the global stage.

What’s more, the theory of “expanded deterrence” was very popular with Moscow leaders in the late 1990s. The idea was that Russia could leverage the threat of its enormous nuclear potential to influence military or political conflicts completely unconnected with strategic nuclear weapons. But this theory did not work out in reality. Perhaps the best illustration of this is when former Russian President Boris Yeltsin reportedly asked his advisers, “Why aren’t they afraid of us?” when he learned that NATO had launched military operations against its ally, former Yugoslavian President Slobodan Milosevic. It turned out that the West understood that Russian leaders would never unleash a nuclear war to defend Milosevic’s regime.

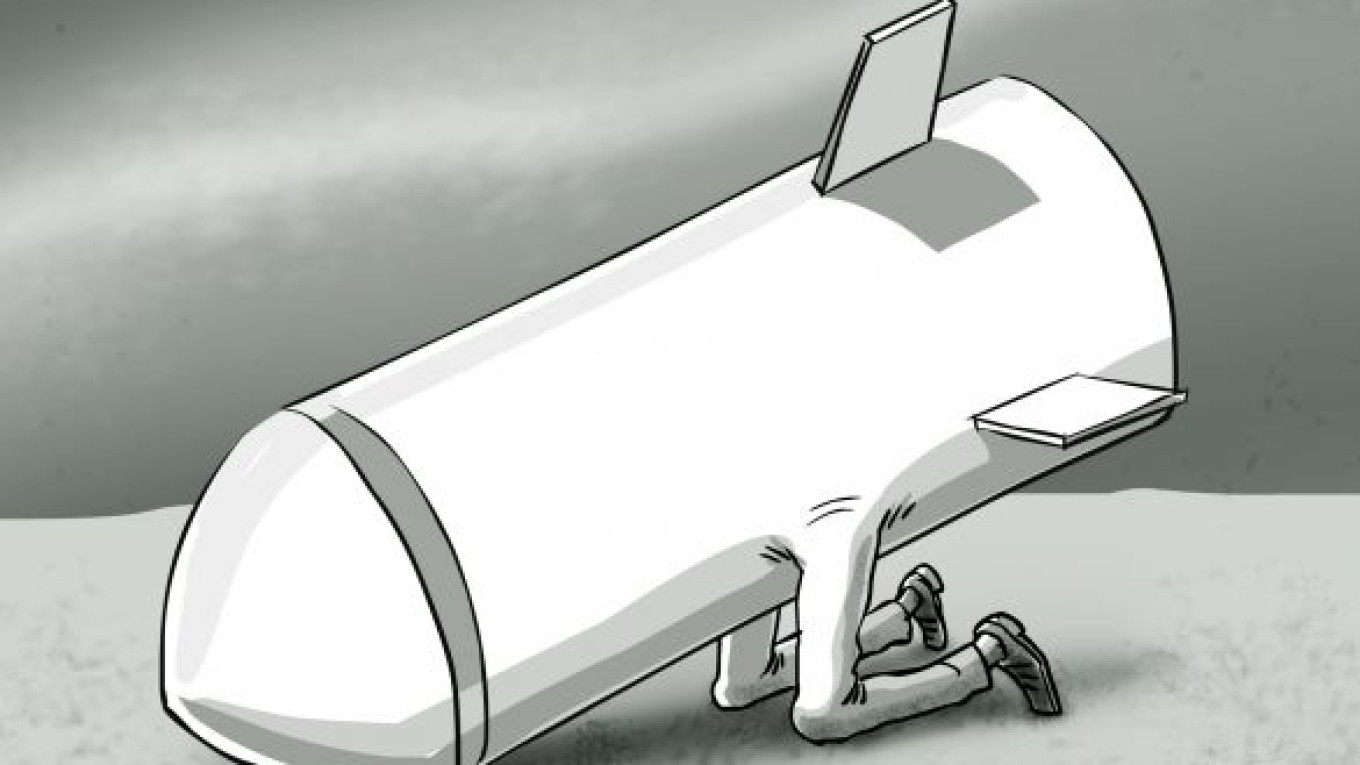

Putin has taken the deterrence game to new absurd heights. The Kremlin has used disputes over strategic nuclear weapons, intermediate-range missiles and missile defense systems as a means for expressing its grievances with Washington and to cast those relations in terms of a military confrontation. Now, Putin has pulled another political sleight of hand by applying the exclusively military doctrine of deterrence to Russia’s entire foreign policy.

This means that any criticism of the Kremlin is now portrayed as part of a larger confrontation that resembles the one that existed during the Cold War. Putin can even claim that the U.S. still adheres to the Cold War theory of deterrence as proof that little has changed since the decades-long U.S.-Soviet confrontation — and that the West still wants to destroy Russia.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.