Back when he was still a head of state and not an occasional organizer of awkward press conferences in Rostov, former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych was renowned for many things.

He stood out for the poor quality of his spoken language, his background in petty criminality, his less than fulsome embrace of the rule of law, and his family's completely unbridled financial corruption.

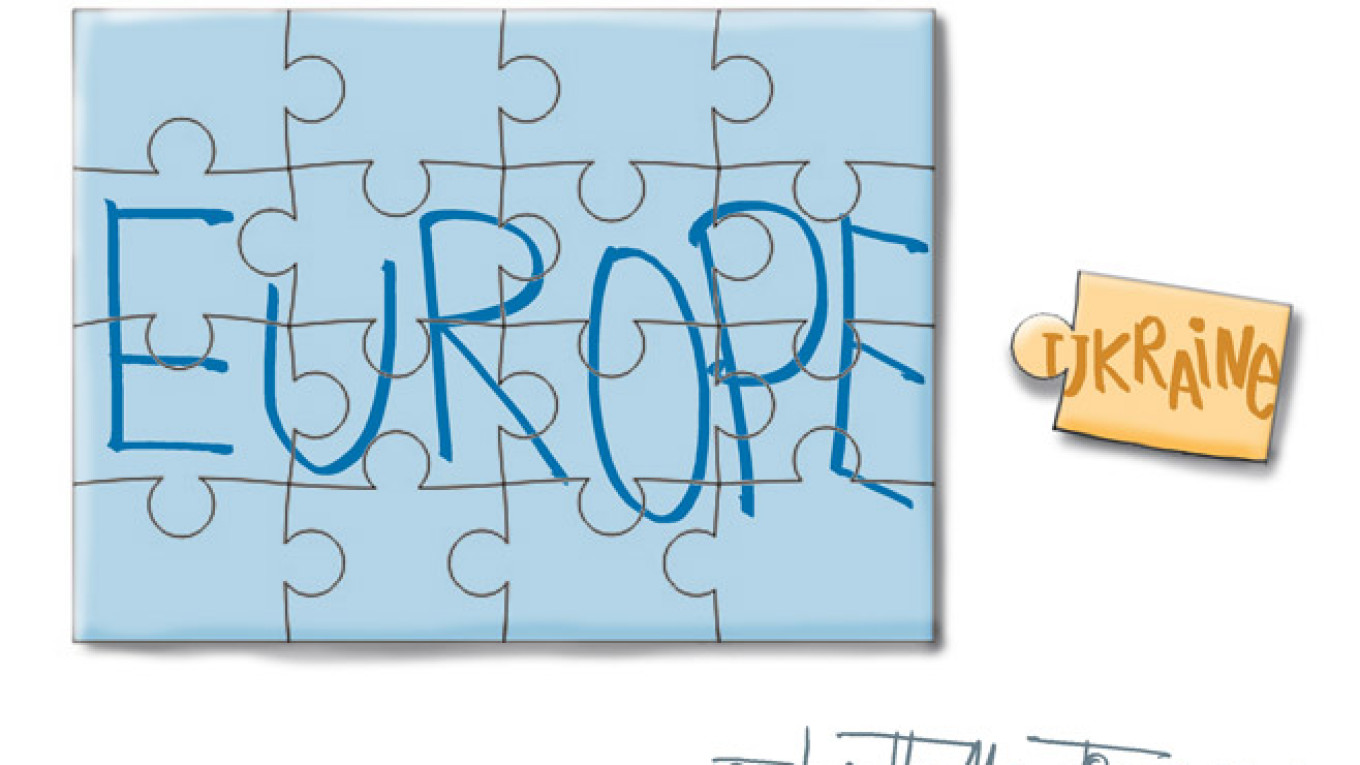

What Yanukovych was not particularly famous for was his enthusiasm for European integration. Why, then, did he go so far in his embrace of the Association Agreement with the European Union? Why did he repeatedly promise to sign a deal that posed such self-evident risks to Ukraine's relationship with Russia?

While there was certainly some simple miscalculation involved, Yanukovych's support was conditioned on a very simple fact: a lot of people in Ukraine are firmly convinced that integration with the European Union is the surest way for their country to get rich and for a "normal life" to be within reach. This conviction has outlived Yanukovych's time in office, and, barring some kind of bizarre or unforeseen occurrence, his successor Petro Poroshenko will sign the Association Agreement today.

The Ukrainian equation of "Europe" with normalcy and prosperity has noticeable domestic roots, but it very clearly did not arise out of a vacuum. In fact, some of the most active proponents of the exceedingly simplistic idea that joining Europe guarantees material prosperity are Europeans, particularly those who work in the enormous bureaucratic machine centered on Brussels.

These people expound at great length and monotonously about the "convergence machine" that they have created, and will tell anyone who wants to listen about the wonders of the EU's legal acquis communaitaire and other bits of obscure EU terminology.

Politicians from the newer and more successful member states, counties like Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, are even better advocates of a "European choice." These people can tell Ukrainians with great clarity, sincerity, and, even more importantly, direct personal experience about the economic and social benefits that EU accession has brought them. By any reckoning they have been by far the most effective advocates of Ukraine's initially cautious and now swiftly accelerating move towards Europe.

The problem is that when they describe the benefits of EU integration, and the "guaranteed" rapid growth that it brings, both the Brussels mandarins and the Eastern Europeans are describing a world that no longer exists.

Europe in 2014 is a much more austere place than it was when Poland, Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic started their long march towards membership. This is true not just in an existential sense, but in very basic questions about material and financial assistance. Put simply, the generous support that helped guide the first round of "new" EU entrants is now politically impossible. If Ukraine wants to become part of Europe, it's going to have to do something that none of the other EU entrants did: it's going to have to pay its own way.

Consider the experience of Poland, the East European country that everyone insists Ukraine can imitate. Poland, as everyone knows, managed to weather the great recession in better health than any other country in Europe. To a large extent this reflected the dynamism of Polish industry and the astute economic management of the Polish government.

However, there is another part of the story that people do not often mention: over the past decade, Poland has received more than $154 billion dollars in direct assistance as a result of being in the EU.

Known as "structural adjustment funds," the money has helped Poland build new roads, repair old ones and generally overcome its baleful socialist inheritance. $154 billion dollars is a lot of money, and that eye-popping figure does not include any of the assistance that Poland received during its initial transition from communism, or any of the funds it received while it was still a candidate for EU membership.

Poland's successes have been genuine, but they have to a large extent been underwritten by a degree of support that Ukraine will never receive. The amount currently on offer by the EU is precisely $0.

It does not take a very active imagination to see how the Kremlin could exploit this situation to its advantage. In order to pursue its "European choice" the Ukrainian government is going to have to embark on an extended and quite severe campaign of austerity: it is going to have to raise gas prices, cut subsidies to industry, raise taxes and cut welfare payments.

In other words, Ukraine is going to have to simultaneously confront all of its own most significant political interest groups and it is going to have to do so on a shoestring budget. The Russians, meanwhile, will be able to offer financial and political support to whatever populist political figure arises to confront the new austerity campaign and they can do so confident that the pro-European groups are going to have to pay their own way.

If Ukrainians want to be in Europe that is entirely their choice to make. But no one should underestimate the difficulty of the path that the country is now embarking on: it is fraught with political and economic difficulty and with an endless series of opportunities for the Russians to play the spoiler.

Mark Adomanis is a MA/MBA candidate at the Lauder Institute at the University of Pennsylvania.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.