On the day President Dmitry Medvedev fired Yury Luzhkov, reporters asked Prime Minister Vladimir Putin to comment on the reason. “The Moscow mayor didn’t get along with the president,” Putin said.

Medvedev’s own explanation wasn’t any more substantial. “As the president of Russia, I have lost my trust in Yury Mikhailovich Luzhkov as the mayor of Moscow,” he told journalists in Shanghai on Sept. 28, the day he signed the dismissal order.

Since then, Medvedev hasn’t explained any further. Although the law apparently allows Medvedev to get away with this vagueness, the president has an obligation to explain the exact reasons why he sacked the Moscow mayor, who held one of the most powerful positions in the country.

Backing the ruling tandem’s silence, one of United Russia’s top leaders, Vyacheslav Volodin, commented the day Luzhkov was sacked: “The president’s decision shouldn’t be discussed. It should be carried out.”

The tandem missed a golden opportunity to make an example of Luzhkov and show that they are serious about tackling corruption. A crackdown on the nation’s top corrupt officials could have a trickle-down effect on mid- and lower-level bureaucrats, as well as businessmen.

Considering their well-known dislike for opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, it wouldn’t be surprising if Putin and Medvedev hadn’t read his investigative report “Luzhkov. Results,” where he lays out in detail several dozen corruption allegations — gathered from open sources — against Luzhkov. Baturina made most of her multibillion-dollar fortune, Nemtsov wrote, by receiving prime Moscow land on an exclusive basis — by Luzhkov’s mayoral decrees — to develop huge commercial real estate projects. Only one of Nemtsov’s allegations would be more than enough to open a criminal investigation into Luzhkov and Baturina.

Even if Putin and Medvedev didn’t read “Luzhkov. Results,” they could have easily watched the “Delo v Kepke” and “Dorogaya Yelena Nikolavna” programs on NTV television last month, which mentioned several corruption allegations against Luzhkov and Baturina. As a last resort, there was always the Federal Security Service, which surely has a thick dossier on Luzhkov’s and Baturina’s activities.

The ruling tandem’s response looks ridiculous and amateurish: The whole country is aware of the corruption allegations, while Putin and Medvedev act as if they know nothing about them.

There are three main reasons why Putin and Medvedev can’t — and won’t — touch the corruption allegations. First, if corruption were included as one of the reasons why Medvedev “lost confidence” in Luzhkov, then both members of the tandem would have to explain why they kept silent about the former mayor’s purported abuses during Putin’s 10 years in power and why the Prosecutor General’s Office never opened a criminal investigation into his activities. Who was protecting Luzhkov all of those years?

Second, trying Luzhkov in court could open up a Pandora’s box of accusations and counteraccusations — including against Putin’s closest allies and perhaps Putin himself. The last thing they want is for Luzhkov to reveal the extent of corruption at the highest levels of government. Luzhkov understood that the tandem was backed into a corner on the issue, which helps explains his intransigence and hubris in the month-long public showdown with Medvedev before his firing.

Corruption by no means started on Putin’s watch, but it has increased sixfold — from roughly $50 billion a year at its peak in the 1990s to more than $300 billion a year in 2009, according to Indem. One reason for this is that the number of state employees sharply increased under Putin — from 485,566 in 1999 to 846,307 in 2008, according to the State Statistics Service. The link is clear and direct: The more bureaucrats, the more corruption.

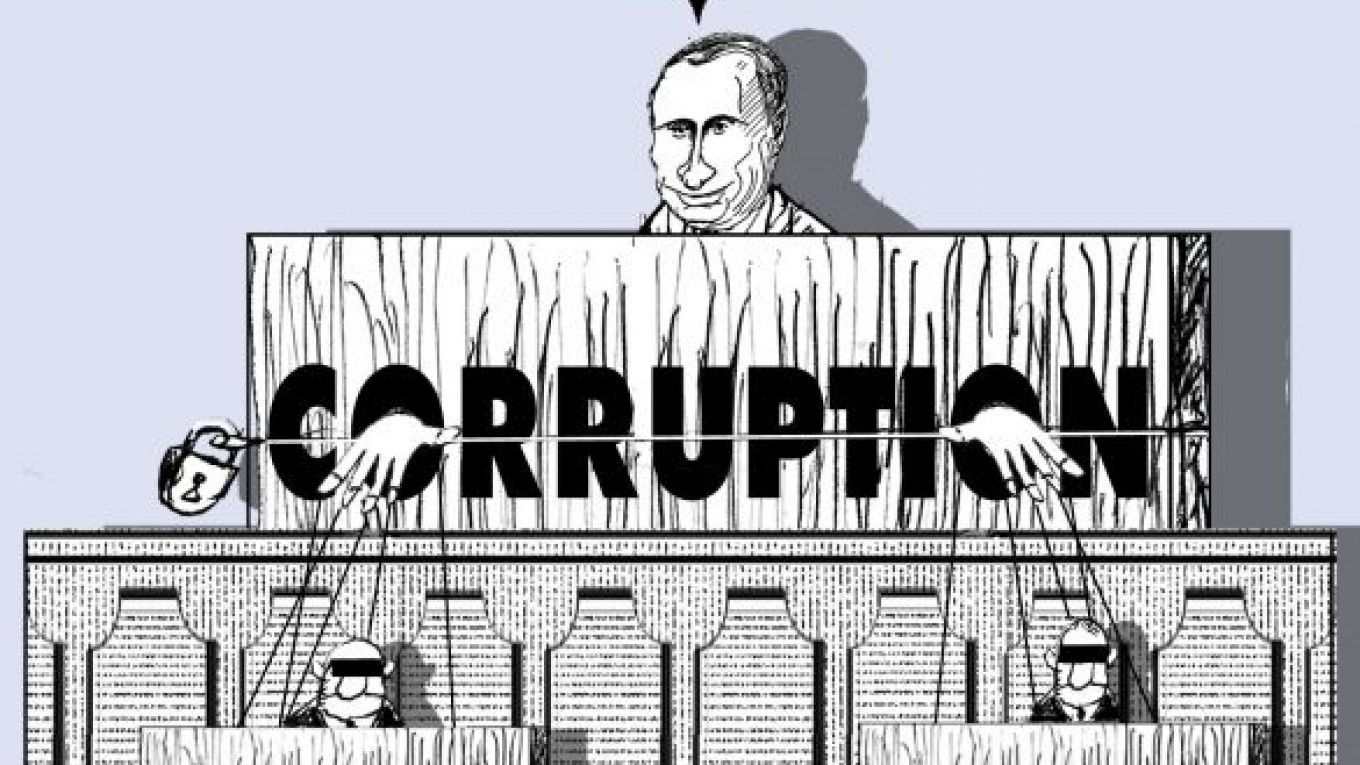

The third and most important reason why no investigation has been opened into Luzhkov is that corruption is one of the foundations on which Putin’s vertical power system is built. Far from fighting corruption, Putin allows it to flourish.

Putin’s system of loyalty is highly dependent on the ability of his army of bureaucrats to embezzle and take bribes. Those who became wealthy under Putin obviously want to keep the current system in place for as long as possible. This is one reason why they are happy to lobby voters to support United Russia and “Putin’s Plan.”

Luzhkov is not the only regional leader to avoid criminal charges. Former Bashkortostan President Murtaza Rakhimov fended off an Audit Chamber investigation into allegations of seizing a host of petrochemical companies and helping his son become the 54th richest Russian with a net worth of $1.2 billion according to Forbes Russia. What’s more, in July Rakhimov was awarded a pension of 750,000 rubles ($24,500) a month. Primorye Governor Sergei Darkin, former Tatarstan President Mintimer Shaimiyev, former Sverdlovsk Governor Eduard Rossel and Kalmykia leader Kirsan Ilyumzhinov are other examples of how deeply entrenched leaders are able to avoid the short arm of the law.

Under Putin, corruption has become a widespread government institution, and this explains why there are so few criminal charges brought against senior officials. Notable exceptions are the selective punishment of Kremlin opponents and the recent charges brought against former Deputy Mayor Alexander Ryabinin — part of a Luzhkov-era investigation that was widely seen as a Kremlin attempt to weaken Luzhkov.

The problem of not pursuing corruption charges, however, goes much deeper than regional leaders. The open secret to closing a criminal investigation — or making sure that one is not opened in the first place — is to pay bribes to prosecutors and investigators. This creates a self-perpetuating chain in which the person being investigated uses money acquired through corruption to bribe himself out of trouble. This begets even more corruption, and the vicious circle keeps going.

The exception is in political cases, where no amount of money can stop real or fabricated charges from being filed against an opponent whom the authorities want to punish. Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky is a case in point.

The Kremlin’s so-called battle against corruption is a farce. Putin’s system in which corruption is tolerated — and thus encouraged — needs to be fundamentally changed, starting at the very top. By filing charges against Luzhkov, Putin would set a high-profile example — something that is badly needed considering that Medvedev’s two-year anti-corruption campaign has brought few results.

In June 2009, Putin famously asked in connection with alleged corruption at Cherkizovsky Market, “Where are the prison terms?” Good question. A real battle against corruption must include jail sentences and the confiscation of illegally acquired property. In addition, State Duma deputies and Federation Council senators should be stripped of their immunity from criminal prosecution.

Since corruption permeates all of society, it would be impossible, of course, to try the hundreds of thousands of people implicated in corruption in one form or another. But at the very least, the battle should begin at the top. A fish rots from the head down.

In the 1970 Soviet classic film “The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed,” Vladimir Vysotsky, who played a police investigator, declared, “A thief should go to jail!” You would think that the bigger the thief, the more compelling it would be to bring criminal charges against him. Not in Russia.

With Khodorkovsky’s arrest in 2003, Putin showed that he has the political will to make a high-profile example as a deterrence to others. Now he should answer his own question, “Where are the prison terms?” by applying his self-declared “dictatorship of the law” to everyone.

Michael Bohm is the opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.