April 14 was a sad anniversary for me. That day marked 10 years since the demise of the old NTV, where I served as director until it was taken over in a Kremlin-backed campaign in 2001. Any objective journalism expert or even simple television viewer will attest to the fact that NTV set a new standard for the country’s television journalism. Year after year, NTV reporters and anchors earned more awards for journalistic excellence than any other channel.

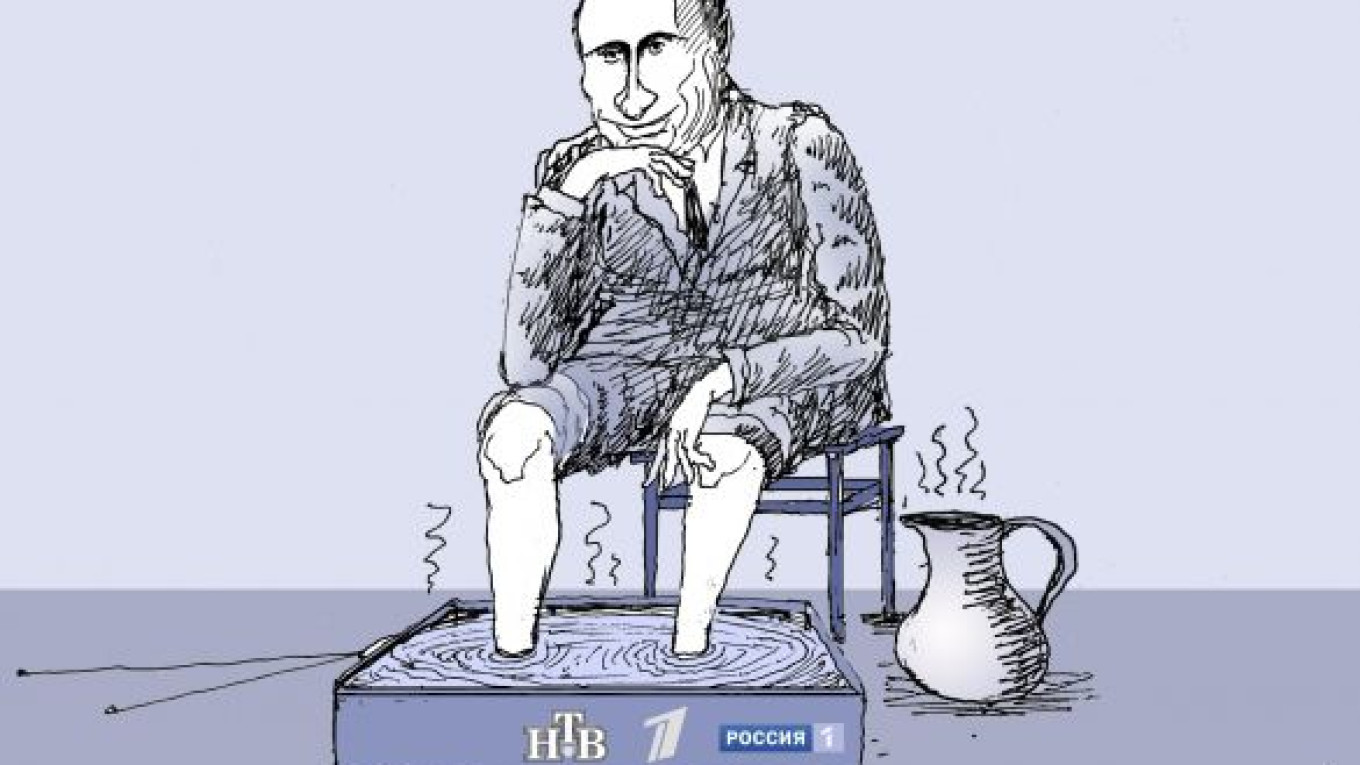

Although the past decade has passed quickly, it is a long period of time. How can I explain to today’s journalism students that Russia once had independent television? Accustomed to watching today’s NTV and the other government-controlled channels, how can those students even begin to imagine that Russia really had a private television network that didn’t maintain a “blacklist” to keep opposition members off the air; didn’t take orders from the Kremlin on what to show or not to show; engaged in real investigative journalism to expose corruption and other abuses among high-ranking officials, including members of the president’s inner circle; and produced numerous satire programs that lampooned the shortcomings and mistakes of top officials.

Although NTV was seized on April 14, 2001, its fate was not decided in a single day. Only four days after Vladimir Putin became president on May 7, 2000, heavily armed Federal Security Service agents wearing camouflage and black masks to hide their identities raided NTV owner Vladimir Gusinsky’s office in central Moscow.

Shortly thereafter, the term “maski-show” became a standard phrase in the Russian vernacular, one that symbolized the criminal era under Putin’s rule — an era marked by arbitrary rule and abuse of power by the Kremlin and its loyal courts and law enforcement agencies.

Putin’s regime, having set out to build its notorious “power vertical,” could not afford the luxury of independent television station free from all state controls and broadcasting to the entire country. The government campaign to take over the network lasted almost two years, with the state bringing all of its resources and leverage to bear: courts, the Prosecutor General’s Office, the FSB, the Federal Tax Service, state-controlled media, propagandists and political consultants.

It is telling that thousands of Russians were outraged at the brazen attack on Russia’s freedom of speech, something that Boris Yeltsin worked so hard to achieve during the 1990s as the country’s first president. The government seizure of NTV prompted unprecedented street demonstrations. To this day, people argue about exactly how many took to the streets in protest — first on Pushkin Square and then at the Ostankino television center. Some say 10,000, others say 20,000, but whatever the case, since the NTV protest there have been very few opposition causes in Russia that have driven so many people to the streets.

In the end, the authorities finally had to take NTV by force, literally storming its offices like a violent gang of street thugs. In response, half of NTV’s reporters left the channel in protest, myself included. We did not believe that the promises that the editorial policy would not change under the management of Kremlin-linked Gazprom-Media.

From the very beginning, we warned Russians that placing NTV under state control was the first step toward building an authoritarian regime. There were those who laughed at us, saying we were exaggerating or simply being overly emotional. We were told that Putin, despite his KGB background, was really liberal and democratic at heart and would never destroy the country’s hard-won freedom-of-speech rights. Moreover, the Kremlin has nothing to do with the destruction of NTV, they said. It is simply an business dispute involving debt between NTV and Gazprom (although Gazprom held only a 30 percent minority stake in NTV).

But the truth of the matter was that Media-MOST? — not NTV — was in debt to foreign banks, not Gazprom. Its largest loan came from Credit Suisse First Boston, which was guaranteed by Gazprom. Then, the Russian authorities demanded the impossible — that Media-MOST return all the money at once. This was a clear attempt to sabotage and destroy the company. All attempts to defend Media-MOST’s legal rights in court were useless, proving that the courts started taking orders from the Kremlin long before the Yukos affair.

In a clear case of due justice, the people who were my most outspoken critics 10 years ago now admit that the government campaign to control NTV and other major television networks has made a complete mockery of freedom of speech and has helped build Putin’s authoritarian model, otherwise known as the vertical power structure.

For example, television journalist Leonid Parfyonov — who was my main opponent 10 years ago and headed the group of journalists who broke with me and stayed at NTV under the Gazprom ownership — used his acceptance speech for the Vladislav Listyev prize in late November to paint a grim but very accurate picture of television in today’s Russia. He said: “Television news has become an important tool of the government. … For television journalists and their managers, top public officials are not newsmakers, but their bosses to whom they report directly. … There is no information at all on news programs, only PR. … Reporters are not journalists, but government employees.”

In my cries against the government seizure of NTV a decade ago, I warned that Putin would destroy freedom of speech on television. Unfortunately, I was correct.

Yevgeny Kiselyov is a political analyst and hosts a political talk show on Inter television in Ukraine.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.