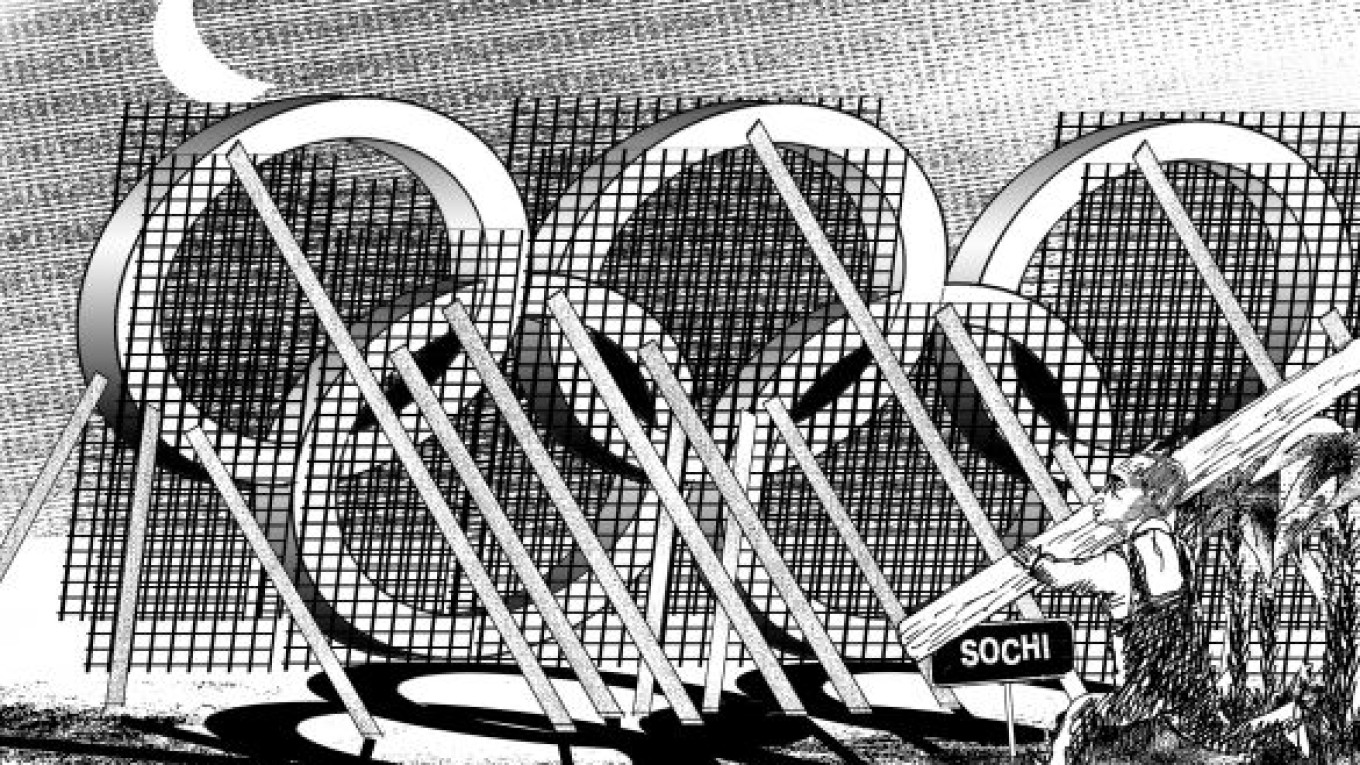

The Olympic flame in Vancouver has barely gone out and four years remain until the opening day of the next Winter Olympics in Sochi. But the first, most important race is already under way. From now until the closing ceremony on Feb. 23, 2014, the world will be on the edge of its seat, wondering whether Russia can pull it off.

The stakes for the Kremlin are huge. The Sochi Olympics are already different from most previous Winter Games, which were largely organized by local or regional authorities with only limited input from federal governments. Sochi, on the other hand, has always been a federal undertaking, driven by Vladimir Putin and controlled directly from Moscow. It is a national priority meant to showcase Russia’s accomplishments. In this respect, it is part of a long line of “propaganda Olympics,” which began in 1936 in Berlin and continued in Moscow in 1980, Seoul in 1988 and, most recently, Beijing two years ago.

If everything goes as planned, by 2014 Putin would already have reclaimed the presidency for a new, six-year term, which would mark his 15th year in power. Just like China’s authorities introduced “New China” to the world in 2008, Putin’s Olympics will put on display the system he has built — which is why I have so many doubts about the outcome.

Putin surely couldn’t have chosen a more challenging test for his system. Not only will all the athletic and tourist facilities and communications and transportation infrastructure be built from scratch, but it will be a winter event on a summer beach. There are many things that could go wrong — and knowing Russia’s history, most of them will.

It is also a major global event that will be held in direct proximity to a restive, lawless region where terrorism is a near-daily occurrence. Even though Canada is one of the world’s safest countries, the security tab in Vancouver still ran at more than one-third of the games’ initial budget.

Finally, it took a lot of chutzpah for the International Olympic Committee to pick Sochi. Heretofore, it had been an exclusive preserve of rich nations. Russia will be the poorest Winter Olympic host — even coming in below Yugoslavia, which hosted the 1984 games in Sarajevo.

Questions might arise about the structural soundness of a roof here and there, but the main facilities in Sochi are likely to be finished on time. Building large on an unlimited budget in an over-the-top, Dubai style has been a particular forte of the Putin system. Politically connected oligarchs working in Sochi, including Oleg Deripaska and Vladimir Potanin, have proven organizational skills. The money is also there, provided by Russian Railways, Sberbank, Rosneft and other state conglomerates. Even though Gazprom has reportedly balked at paying its $2 billion sponsorship, the budget is already estimated to be about $14 billion. Putin and other top officials make regular personal visits to Sochi to make sure that everything is on schedule.

But a successful Olympics is so much more than facilities and equipment. For many visitors the fun is not only attending the events but also seeing the host city, straying from the beaten path, discovering quaint local restaurants and driving around the countryside.

That is where problems will arise. Putin’s Russia functions relatively well for the wealthy who inhabit gated communities along Moscow’s elite Rublyovskoye Shosse, get chauffeured around pot holes and traffic jams in luxury limousines, eat at expensive restaurants and vacation abroad. For everyone else, the infrastructure of daily life is a lot sparser and tougher — and exponentially worse outside Moscow.

It will be interesting to see where the organizers find the kind of cheerful, multilingual volunteers who steered crowds to Olympic venues in Turin and Vancouver. They are probably not going to find them in Sochi. Sochi authorities already complained to Putin last year that locals don’t speak much English. But this is only part of the problem. More to the point, the Olympics have already disrupted and dismayed Sochi residents. Many have been displaced to make room for Olympic sites. The rest will have to live for the next four years on a construction site.

In most countries, Winter Olympics are staged to boost tourism and provide revenues for local businesses and services. But because there are so few small businesses, local restaurants, nice boutiques selling regional products and private hotels, Sochi residents will benefit very little from the Olympics. The lion’s share of visitors’ money will end up at large hotel and restaurant chains.

The Olympics is also about organization, and this could become the ultimate undoing of the Sochi games. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the bureaucratic infrastructure in Russia has disintegrated. Or rather, it has been privatized. Officials at every level have stopped doing their jobs and have become more like feudal lords, using their position either to siphon money from the budget or get kickbacks from the people they are supposed to serve. In the Soviet Union, the bureaucracy was unwieldy and inefficient. Today, bureaucrats simply refuse to do anything unless they see an opportunity to make some money on the side.

The results are plain. Police don’t protect citizens but rob and harass them. Sports officials don’t generate Olympic victories but live high on the hog at international competitions. Sochi 2014 may very well earn the dishonorable distinction of being the costliest and most unsuccessful Olympic Games in history.

In 2008, the Beijing Olympics showed that China’s post-communist system, for all its problems and shortcomings, definitely works. Four years from now, the Sochi Olympics may reveal that the post-Soviet Russia, for all its pretensions, doesn’t.

Alexei Bayer, a native Muscovite, is a New York-based economist.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.