Yegor Gaidar, who led post-Soviet Russia’s first government reforms from 1991 to 1992, will be buried in Moscow on Saturday. People will remember Gaidar most of all for the economic reforms that he designed and implemented.

One of the biggest myths surrounding Gaidar was that his reforms bankrupted the country. Many Russians still believe that it was Gaidar who turned Russians’ hard-earned savings into useless paper. His reforms are blamed for dismantling what was mistakenly believed to be an economically viable Soviet economy and for crippling the country’s industrial enterprises and military complex.

In reality, of course, the Soviet economy was already in ruins by the time that Gaidar was invited by President Boris Yeltsin to join the government in November 1991. Oil prices had dropped to record lows, and the economy had reached the end of its rope after decades of spending far beyond its means in an arms race in which it was clearly in no financial position to compete. Moreover, the West was generations above the Soviet Union in terms of computerization and high technology. Gold and foreign currency reserves had dwindled to a paltry $30 million (compared with more than $450 billion today). In short, the Soviet Union was bankrupt.

At a time when Gaidar was trying to reform the economy, the country was unable to pay its foreign debt, while other countries and foreign banks, fearing imminent bankruptcy, cut off loans. Instead, the only thing that was being sent to Russia from abroad was humanitarian aid, as if it were a starving African country. Cabinet meetings were dominating by desperate discussions about how to save the country from famine. It is difficult for young Muscovites, who only know the capital as a modern, wealthy city, to imagine that Moscow was once a squalid, poverty-stricken city. When Gaidar was put in charge of the economy, people were scavenging the city looking for basic food items, while market shelves were empty in virtually every store. The most-prized thing you could bring to your friends and relatives from a business trip abroad was food — a piece of cheese, cooking oil, sausage or some fruits and vegetables.

This is the crippled Russia that Gaidar inherited when he set out to reform the collapsed economy. Nonetheless, most Russians are convinced that Gaidar was responsible for the country’s economic problems. Perhaps it was designed that way. Yeltsin put Gaidar in a position that nobody could have come out of unscathed. He was a convenient scapegoat for all of the country’s accumulated social and economic problems. Strangely enough, Gaidar understood this better than anyone, and he should be given full credit for taking on these onerous and thankless responsibilities.

Another fact that few Russians understand is that the foundation for Russia’s economic growth during the period from 2000 to 2008 was laid during Gaidar’s reforms. I remember how in the beginning of the 1990s Gaidar was fond of saying that future Russian economic growth was inevitable, just like in any other country making the transition to a modern market economy. And this is exactly what happened. Unfortunately, Gaidar’s contributions are rarely acknowledged, while most Russians are generous in their praise of Vladimir Putin for his supposed role in producing the economic boom during his two presidential terms.

During the 1990s, Gaidar tried to stay loyal to the Kremlin, consistently avoiding crossing over to the opposition. Sometimes, however, he wasn’t able to hold back, such as when he resigned from Yeltsin’s presidential council at the beginning of the first Chechen war as a sign of protest again the bloodbath. He even participated in several anti-war protests and demonstrations. Yet this was an exception that underlined Gaidar’s loyalty to a lifetime rule that he explained in an interview shortly before his death: “Over time, I decided that our country has gone through enough revolutions and it’s better to reform from the inside. If you want to reform from the inside, you should at least belong to the select group of economic and political advisers that is connected with the ruling elite. Only then is there a chance to get something done.”

Gaidar was correct. There has never been a case in Russian history where economic, political or social reforms have been carried out from the bottom-up. Reforms in Russia have always been implemented from the top-down and only once the ruling elite realized that the country might collapse if drastic measures weren’t taken.

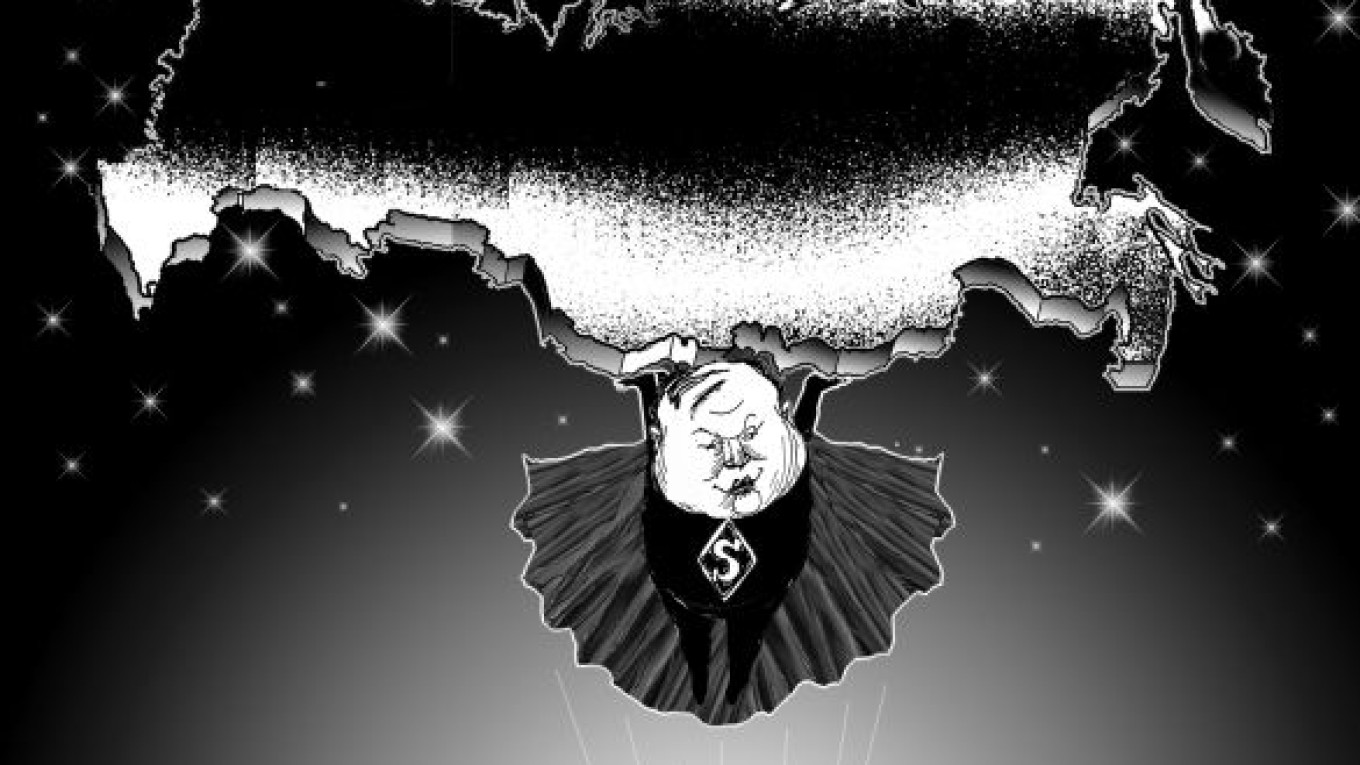

The problem today is that there are no more great reformers like Gaidar left in the ruling elite. There is nobody who is willing to take the risks and assume the huge responsibilities for reforming the country. Instead, our political leaders consist almost exclusively of power-hungry provincial bureaucrats — of which too many of them are former KGB officers — whose single concern is maintaining and increasing their hold on power, amassing personal fortunes and showing contempt for the opposition and public opinion.

After Gaidar left the government, he agonized over the economic difficulties that Russians incurred in the 1990s, although it is very difficult to imagine that he, or anyone else, could have done better given the circumstances. Although Gaidar, a quintessential member of the Moscow intelligentsia, tried to suppress his feelings of anguish, it seemed at times that he knew that his untimely end was near. This makes Gaidar an even more tragic figure in a country that has suffered so much from its tragic history.

Yevgeny Kiselyov is a political analyst and hosts a political talk show on Inter television in Ukraine.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.