On the evening of Nov. 3 in St. Petersburg, the staff of the LGBT organization La Sky, which provides assistance to people who are HIV-positive, were enjoying their traditional "Rainbow Tea" in the office. Suddenly two people in masks broke into the room. They were armed with pneumatic pistols and immediately opened fire. The first person hit was a young woman, who suffered a minor injuries. But then the attackers shot the activist and video blogger Dmitry Chizhevsky in the left eye. Right now he is in the hospital and doctors have said he will not regain sight in that eye.

On Nov. 4, also in St. Petersburg, three Central Asian migrants were killed in separate incidents. On that same day, a mob of nationalists broke into a metro train car and beat up migrant workers and people of non-Slavic appearance. The police ended up arresting more than 100 nationalists.

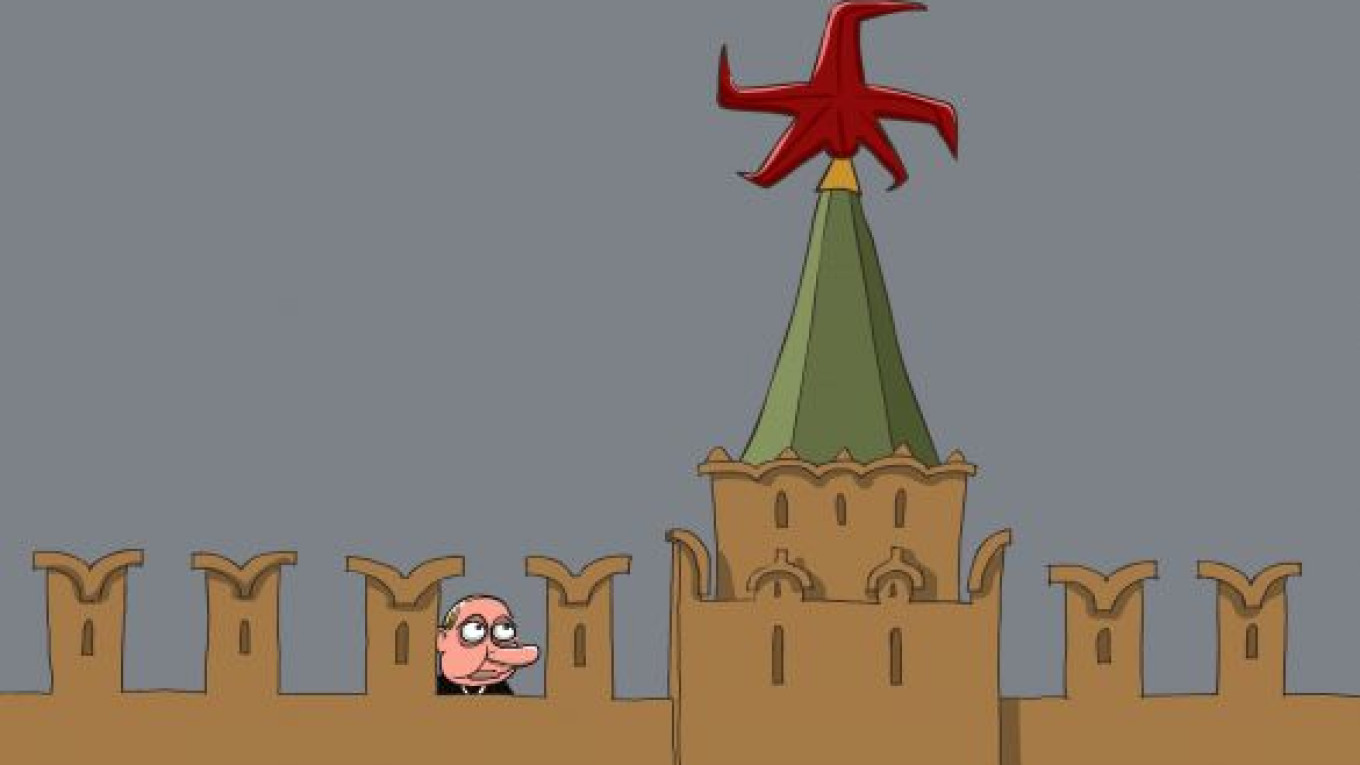

With the increase of violence against gays and migrants, Russia is becoming more like Germany in the 1930s, when storm troopers ruled the streets, beating up and killing Jews and other minorities with impunity.

This wave of persecution and violence initiated against two of society's most vulnerable groups — the LGBT community and migrants — was set in motion long ago. It could have been foreseen last year when the State Duma passed the notorious law banning "homosexual propaganda" and state-controlled television unleashed anti-gay hysteria, accusing the LGBT community of pedophilia and other mortal sins. The violence against migrants could be expected after they became one of the key election issues in various Russian regions.

As Chizhevsky stated in his interview to Slon.ru: "I blame deputies Yelena Mizulina, Vitaly Milonov and all the villains who whipped up this homophobia. It is their fault. They are the true criminals."

Milonov, the deputy of the St. Petersburg Legislative Assembly famous for initiating a number of homophobic laws and actions, said what happened at La Sky was "a planned provocation" done by the LGBT activists themselves. Although, in Milonov's view, everyone has the right to "give a beating" to anyone in a gay pride parade.

In an interview to the news website Fontanka.ru, Milonov said: "Who is preventing them from living their lives? They are the ones who are going out to march against normal society, going out and publicly showing children their perverted world view. That is not done here. We have to protect children from this. This is not a human right. It is the rights of the sick and perverted."

Since the rights of "perverts" are not protected by the law in Russia, gay people have no choice but to flee the country. The St. Petersburg LGBT organization Vykhod reported that in the past two years just a few people asked for help in getting political asylum abroad, but now two or three people approach them every week. Vykhod's coordinator for legal aid programs, Kseniya Kirichenko, told Radio Liberty: "Single-sex families have begun to approach us. They are afraid that their children might be taken from them. The Duma already has a draft law on this, which might be passed at any time."

Journalist Oleg Kashin, who now lives in Switzerland, thinks that emigration is the best bet for both the LGBT community and opposition activists. Three years ago, two masked men beat Kashin with a metal crowbar to avenge his political articles. It was a miracle he survived the brutal attack. The beating, which was caught on surveillance video, was highly publicized and supposedly taken under the "personal control" of then-president Dmitry Medvedev.

Since then, the investigation has not moved forward an inch. In an interview to Slon.ru, Kashin predicted that "nothing good will happen for the next 20 years in Russia" and proposed that people "pack their bags and move away — if only to Estonia."

But emigration is a way out only for the young, mobile and adaptable. It is not the answer for millions of other Russians. It is sad to admit that in the 21st century there are no mechanisms in the country or the international community to stop the country's rapid slide into the abyss of violence. In the recent past, it seemed that the country was heading "back to the U.S.S.R.," but now the situation is more reminiscent of Germany in the 1930s, when gangs of storm troopers ruled the streets, beating up and killing Jews and others with impunity.

The West has turned out to be helpless, unable even to protect the rights of its own citizens — for example, the crew of the Greenpeace ship Arctic Sunrise. For weeks, the entire crew, from captain to cook,has been held in pretrial detention in a frigid and decrepit prison that has changed little since the gulag.

Calls to boycott the Olympic Games in Sochi or impose economic sanctions are met with little support and do not appear to be realistic. But the international community does have a powerful weapon that may be used against those who violate human rights in Russia. This is the U.S. Magnitsky Act and similar laws in European countries. The refusal to issue visas to those who have committed rights violations or to permit them to hold assets and real estate in these countries might make them think about the consequences of their actions. These sanctions must be applied to everyone — from Duma deputies who vote for laws violating rights to the state and law enforcement officials who uphold and abuse them.

Paradoxically, this might help both the repressed and the repressors, since increased human rights violations leads the country's leaders down a slippery slope — right down to a tribunal in The Hague.

Victor Davidoff is a Moscow-based writer and journalist who follows the Russian blogosphere in his biweekly column.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.