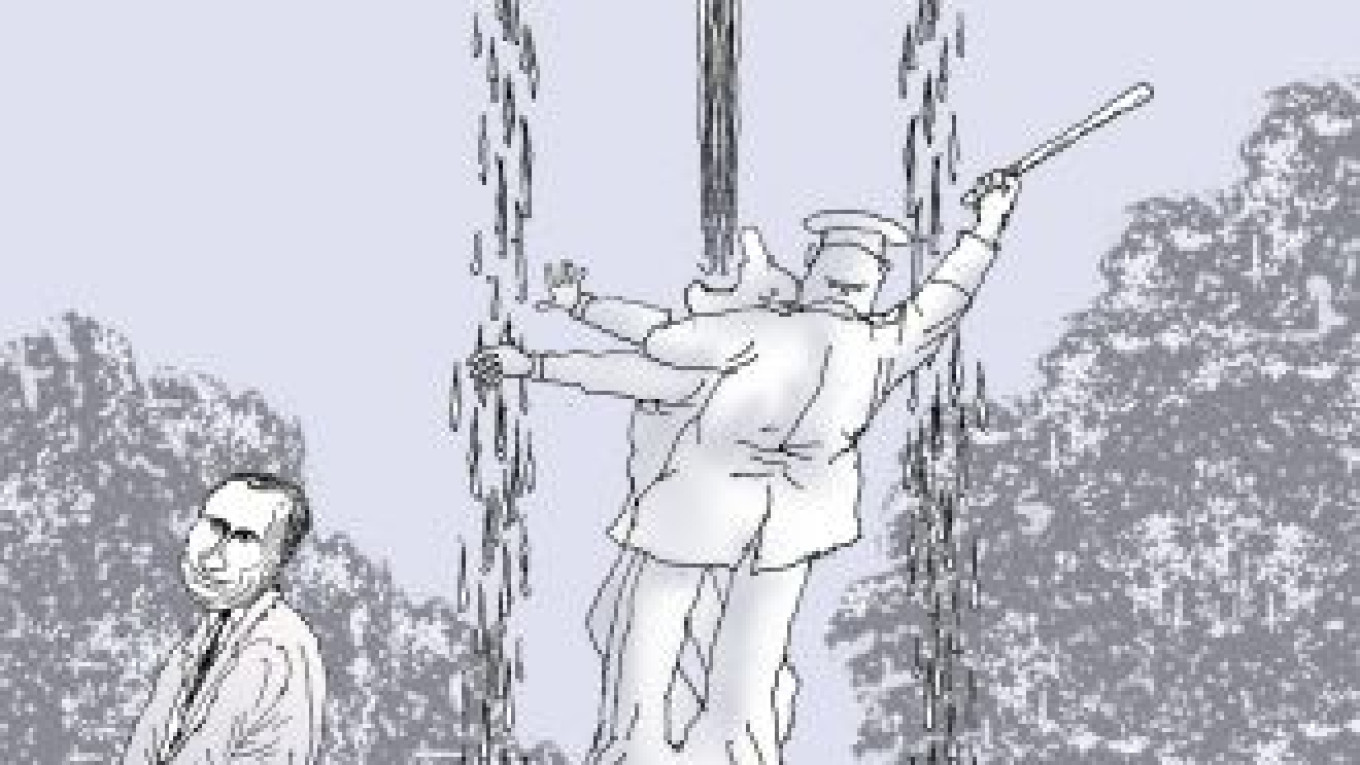

When Yury Shevchuk, a rock musician and outspoken Kremlin critic, met with Prime Minister Vladimir Putin two weeks ago, it was truly a historic event. After all, we have waited 10 years for this precious moment — when Putin would finally go one-on-one with a real critic of his regime.

Indeed, most Putin-watchers — including many of his loyal supporters — have grown bored with the soft, self-censored questions from journalists or Putin’s highly staged call-in shows in which some of the more probing questions in years past have included:

1. “It is well-known that great people suffer from depression. Do you have depression?”

2. “Do you like going to the banya?”

3. “Do you use a cellular phone?”

4. “Is it true you promised to hang [Georgian President Mikheil] Saakashvili by one of his body parts?”

5. “Why does Russia’s national soccer team perform so poorly?”

6. “Why don’t the national television channels show gymnastics in the morning anymore?”

7. “How will you celebrate New Year’s Eve?”

8. “Are you romantic?”

9. “When will we see the first snowfall?”

10. “Do you let stupid questions get through on your program?”

Opposition leader Boris Nemtsov has been begging for years to have the chance to debate Putin live on television. When he was a State Duma deputy in 2003, Nemtsov tried to introduce a law to force presidential candidates, including incumbents, to participate in debates on live television.

Nemtsov understands, as the Russian saying goes, that the truth comes out during an argument. Unfortunately, there have been far too few real arguments and little truth during Putin’s reign. Over the past 10 years, Putin and top United Russia members have flatly refused to participate in debates. In addition, leading opposition figures such as Nemtsov, Vladimir Ryzhkov, Mikhail Kasyanov and Garry Kasparov say they have been kept on a Kremlin “black list” that prevents them from appearing on government-

controlled television.

Therefore, it was highly unusual that Putin agreed to answer questions from one of his most vocal opponents in an uncontrolled environment and with cameras rolling — all the more since Shevchuk is a legendary rock musician who wields enormous influence over many Russians.

Why did Putin take the risk? Maybe he thought that Shevchuk would heed the advice of the phone caller who rang him up beforehand and advised him not to ask the prime minister any tough questions. (Shevchuk suggested that the caller was a Putin aide; Putin denied it.) Alternatively, perhaps Putin was trying to rebrand himself by presenting a new, “liberal” face as he considers a 2012 presidential campaign.

In any case, it was clear that Putin overestimated his ability to field tough questions from a genuine opponent. But, then again, he has had little experience doing this, so it is perfectly understandable why he appeared uncomfortable, irritated and a bit rough. He was not the cool and confident Putin we have come to know so well from his daily, choreographed television appearances.

Putin relied mostly on smokescreen tactics in responding to Shevchuk. For example, when asked about the lack of freedom of the press in the country, Putin’s only answer was: “Without the normal development of democracy, there is no future for our country.”

When asked why opposition rallies are regularly broken up by OMON forces, Putin said protesters shouldn’t block the people’s access to hospitals — something that has never happened in the country. What’s more, Putin said, “If I see that people … are calling attention to crucial issues that the authorities should pay attention to, what can be wrong with that? We should say, ‘thank you.’” Two days later, during an opposition rally on Moscow’s Triumfalnaya Ploshchad, the 150 people who were detained and roughly two dozen who claimed that they were attacked by law enforcement officials got a good taste of Putin’s “thank you.”

Finally, when asked about poor conditions for coal miners, Putin gave a lecture about the difference between coke coal and power-generating coal. “I know about this,” Shevchuk said despondently, drooping his head in apparent realization that he wasn’t going to get a straight answer.

One of Putin’s replies caught some by surprise. In answer to Shevchuk’s question about police abuse of power, Putin said: “According to our cultural tradition, as soon as someone gets an official position … he tries to use it to make money. … This is characteristic of every sphere in which someone obtains authority and the opportunity to make enormous money from administrative economic rent.”

Who was Putin referring to? Perhaps he meant the top management of Rosneft, which received the lion’s share of Yukos after the government effectively expropriated the company. Maybe he was referring to Gunvor, the energy trading company with $53 billion in revenues and headed by Gennady Timchenko, an old Putin colleague from his days in the St. Petersburg mayor’s office. Perhaps it was even a veiled confession on Putin’s part?

Despite his best intentions, Putin failed in his attempt to play the role of a democratic politician who respects the opposition’s rights and is tolerant of their opinions. He gave himself away when Shevchuk stood up and offered a toast, wishing that the country’s children will grow up not in a “corrupt, totalitarian, authoritarian [country] with one political party … but in an enlightened, democratic country in which everyone is equal before the law.”

As Shevchuk ended his toast while everyone’s glasses were still raised, someone at the table said, “We are raising glasses of water! No one toasts with water.”

Grinning like a Cheshire cat, Putin retorted, “The beverage fits the toast!” (One colloquial meaning of “water” in Russian is meaningless, empty words or padding.)

Kudos to Putin for his quick and sharp wit. But in those five words, he instantly threw off his liberal mask and revealed his true disdain toward political opponents, democracy and pluralism.

Shevchuk, clearly hoping for a breakthrough dialogue with the prime minister, prefaced his questions to Putin by saying, “This may be the beginning of a genuine civil society.” But judging by Putin’s responses, it may very well have marked the end.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.