Russia's state-controlled media has been hailing the anniversary of Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu's first year in office almost as if he were the president. Such fanfare never greeted the first anniversary of any of his predecessors. Obviously, the general consensus among his colleagues is that Shoigu is headed for bigger and better things and so every move he makes attracts a great deal of attention. Shoigu has also broken the stubborn stereotype that all post-Soviet defense ministers experience a sharp drop in popularity, just as Soviet-era agriculture ministers often met with political disaster after taking office. Shoigu has achieved the impossible: even after 365 days as defense minister, he remains the most popular figure in the government.

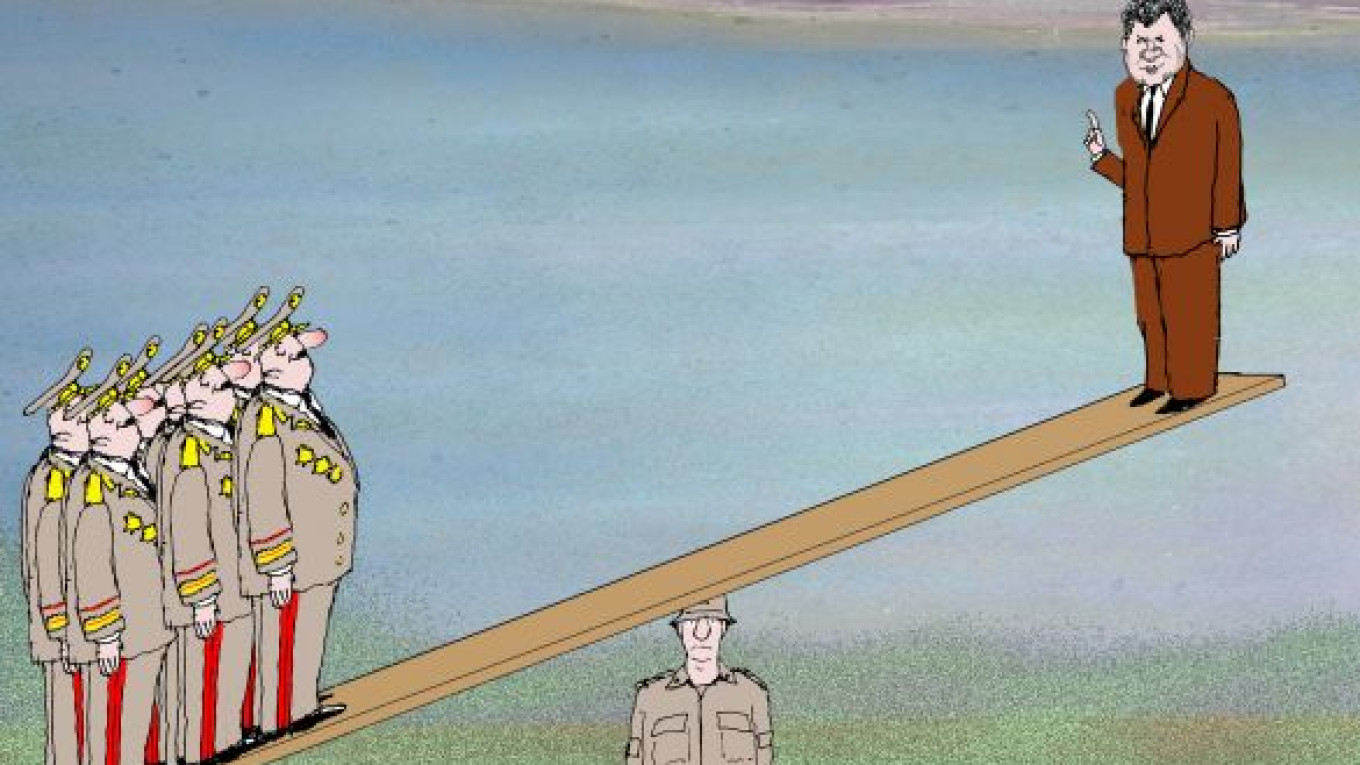

The reports of Shoigu's actions have been almost universally positive. They point to his relaxed and respectful leadership style with subordinates and his refusal to try to "break the army's back" as the top brass claims former Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov had done. The only problem is that when journalists attempt to illustrate his accomplishments, they can only cite absurd trivialities such as decisions to let cadets once again march in military parades or prohibit civilian chefs from preparing food for military exercises. At the same time, they conveniently overlook the fact that Shoigu bowed to pressure from the military lobby to reopen 15,000 places for cadets and students in military academies and training schools. This comes at a time when 40,000 officers have already been shunted out of the regular ranks and hold no paying positions, and when 10,000 lieutenants are serving in the inferior rank of sergeant. The only explanation for this move is that Shoigu decided not to fight with generals, each of whom defends the interests of the military academy from which he graduated. However, this decision threatens to undo one of the main accomplishments of Serdyukov's reforms — namely, the reduction in excess officers. When Serdyukov began his reforms, the Russian army had about one officer for every two privates.

Shoigu's "respectful" manner can be explained by one simple fact: as the new defense minister, he has had nothing that "needed breaking." Serdyukov — whom everyone now curses — had already done all the "dirty" work for him by dismissing more than 200,000 officers and warrant officers and transforming divisions into brigades. So far, Shoigu has not had to backtrack on Serdyukov's most important reform — the shift away from maintaining a million-man mass mobilization army. In effect, Shoigu has used his authority and strong popularity to "ennoble" Serdyukov's ruthless reforms. That is the typical approach for all Russian reforms. First, corrupt, inept or self-interested officials let the situation get almost completely out of hand. Then, a brutal reformer comes along who "makes the chips really fly." Finally, a more compassionate official "picks up the pieces" and continues on from there.

Just the same, I think it was premature to report on Shoigu's accomplishments in office because it seems that he is only now reaching the turning point as defense minister. One month ago, Shoigu made a surprise announcement, indicating that he is aware of the main problem the armed forces face today. "The military is no longer chasing down potential recruits and attempting to 'nab' them at induction centers. Whether we like it or not, this must become a professional army or else conscripts must serve for at least five years. Today's weapons systems are so complex that conscripts cannot train adequately to operate them in just one or even two years," he said.

Moreover, Shoigu has said that the number of conscripts will be reduced by the thousands, and promised to release the exact figure in November. He already hinted at the number during an interview with Rossia television. "We must have resources for mobilization," he said. "A decision has been made to create four reserve armies. By 2020, conscripts will no longer take part in military operations." What the military calls a "combined-arms" army consists of 40,000 to 50,000 soldiers and officers. The Russian army currently has 10 such armies. If Shoigu is referring to this type of formation, then he is talking about preparing up to 300,000 reserve soldiers. Former chief of the General Staff Nikolai Makarov had called for 700,000 reservists. This raises the question: if anywhere from 300,000 to 700,000 soldiers could be called up in the event of war, what need is there to corral at least 350,000 young conscripts in addition to this every year?

Shoigu probably plans to make his announcement about conscripts during a meeting of the top brass that the country's senior leadership typically also attends. But here he will hit a snag: like it or not, Shoigu will have to explain to President Vladimir Putin that it is impossible to carry out his order to fully staff a million-man army by Jan. 1, 2015. If the army were reduced to a more reasonable 600,000 to 700,000 soldiers and the number of conscripts cut to 70,000 to 100,000, that would be a new and major step forward for military reforms. But if the total size of the army is not reduced, the number of conscripts will not be cut either. After all, only the semblance of a mass call-up enables military officials to juggle the numbers and make it look as if Russia can reach a million-man army.

The moment Shoigu makes a sensible reduction in the size of the armed forces, he will have difficulty maintaining his laid-back management style. This is because he will have to decide what to do with the excessive number of senior officers that will appear when the additional 15,000 students admitted to military academies graduate and begin serving as officers. At that point, a number of generals who are currently singing Shoigu's praises will probably change their tune.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.