Immediately after taking part in an Independence Day parade in Kiev on Sunday, Ukrainian military units returned to the war zone in the country's south and east. The historical precedence will be obvious to anyone who grew up in Soviet society. In 1941, Soviet troops took part in the Nov. 7 parade in Moscow commemorating the 1917 Revolution before immediately mobilizing to defend Moscow from the German offensive.

In another parallel from Russian history, on Sunday, pro-Russian rebels in Donetsk paraded several dozen Ukrainian prisoners of war down the main streets of the city. In 1944, Soviet troops led tens of thousands of German prisoners of war through the streets of the capital.

Both sides, it appears, are fiercely clinging to their positions, displaying their resolve in eerie evocations of World War II.

That is important to keep in mind as the Customs Union summit between the presidents of Russia and Ukraine is being held today in Minsk. Many observers, including German Chancellor Angela Merkel, hold low expectations for the outcome of that meeting.

For now, the only progress has been in the form of tactical victories by those who have assumed the role of mediators in this conflict — namely, Belarussian President Alexander Lukashenko.

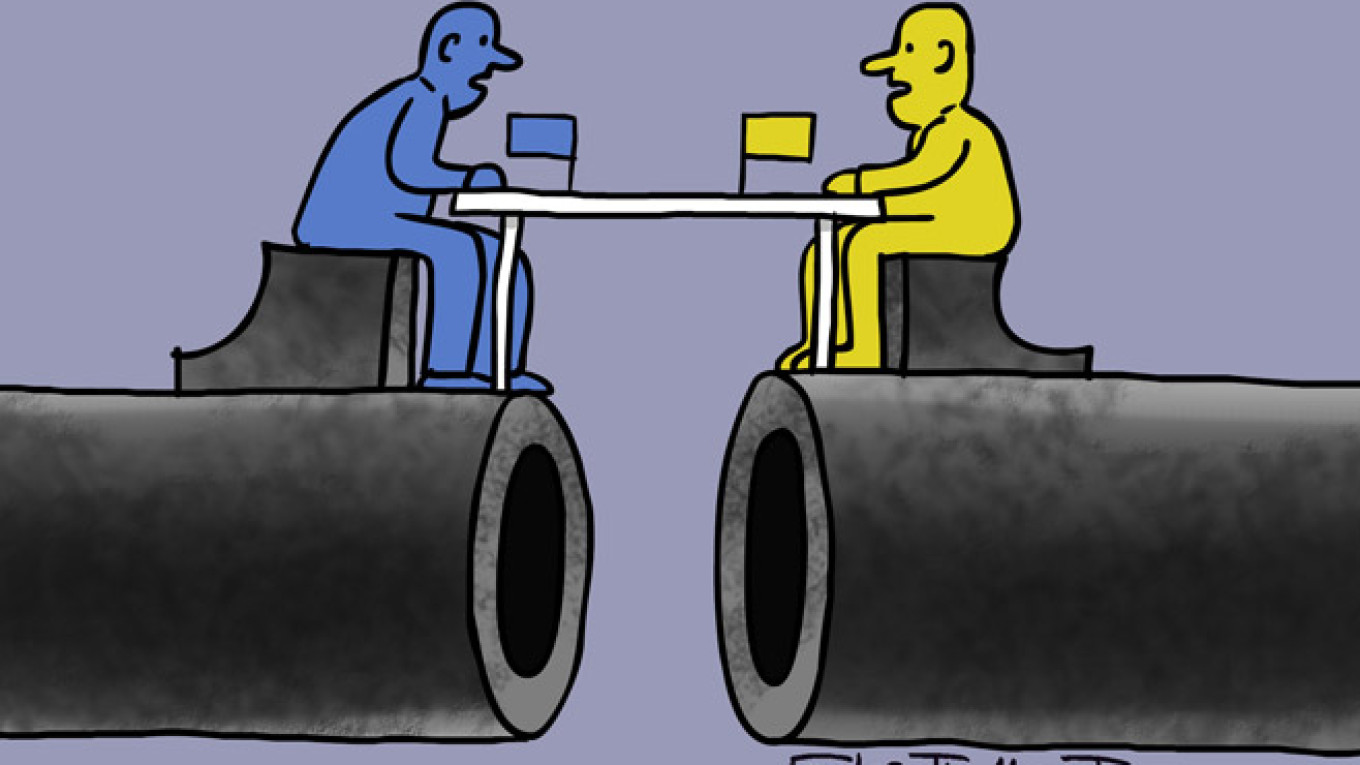

The Kremlin insists that the turmoil in eastern and southern Ukraine is an internal conflict not involving Russia, and that Kiev should therefore negotiate with the separatists themselves. (Perhaps that is why the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic has replaced its former Russian leaders with "native" residents of the Donbass.) However, the Ukrainian government maintains that Russia instigated the aggression and that Kiev should negotiate directly with Moscow.

In order to bring the two leaders together, mediators had to invent a previously unplanned summit at which Putin and Poroshenko would ostensibly participate in general negotiations on how Ukraine's Association Agreement with the EU will affect the economies of the Customs Union member states. Considering the serious losses the Russian economy has already suffered as a result of Western sanctions, it is almost funny to recall that Moscow first sought to thwart that agreement with the argument that it could have damaged Russia's economy.

Credit is certainly due to Lukashenko, who took the opportunity to place himself at the center of world politics. It was he who proposed holding negotiations in this format, claiming that leaders of the "Eurasian Three" [Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan] and Ukraine should "sit down and talk," that they should "discuss what is actually happening" because nobody could have "imagined that such a mess could arise between such close and fraternal peoples."

Lukashenko was also the one who invited EU representatives to the meeting in Minsk, including EU foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton, European Trade Commissioner Karel de Gucht and European Energy Commissioner Guenther Oettinger.

But despite the fact that all the necessary conditions have been created, bilateral Russian-Ukrainian talks might not take place. "I would not like to talk of a final agreement," Putin's spokesman Dmitry Peskov said, casting doubt on any direct talks between Putin and Poroshenko.

"These are complex negotiations and might therefore be held in a variety of formats. Again, it is still too early to say when and how these negotiations will take place," he said.

The main problem is that it remains unclear exactly what might serve as the basis of a compromise between Russia and Ukraine.

With Ukrainian forces embroiled in street battles in Donetsk and Luhansk, Kiev apparently hopes to win by military means and is demanding that Moscow cease its support for the separatists. But Moscow, for its part, seems unwilling to stop supplying the separatists with weapons.

The Kremlin instead hopes to freeze the conflict in its current stage, essentially giving legitimacy to the self-proclaimed republics of Donetsk and Luhansk and creating a Bosnia scenario in which ethnic divisions are legitimized.

Moscow clearly has no intention of reducing its support for the separatists, and it is no coincidence that reports of the upcoming meeting between Putin and Poroshenko were almost immediately followed by media reports that a Russian tactical force of 1,200 armed men and about 100 pieces of military hardware had entered Luhansk. Several days later, Donetsk separatists announced that they had formed several military units, including two tank battalions and several artillery battalions.

And even if we are meant to believe the Kremlin's assertions that it has nothing to do with Ukraine, how are we to understand the enthusiastic reports on state-controlled Russian television that the militia forces have ever greater numbers of tanks, armored personnel carriers and rocket launchers? The reporters claim that the separatists have seized the weapons from Ukrainian forces, but they do not explain how the separatists are replenishing their ammunition or providing fuel for those vehicles amid very intense fighting.

Even if money does not grow on trees, it would seem that ammunition and fuel supplies do — at least in eastern and southern Ukraine.

However, it would obviously be impossible to implement the "Bosnian scenario" that Moscow officials have recently proposed. After all, the Bosnian settlement gave each of the parties in that conflict control over a specific territory, and it would spell political suicide for Poroshenko to agree to such an arrangement.

But Ukraine's only leverage against Russia is the threat of new Western sanctions, which Putin will not bow to because doing so would mean certain political humiliation.

In any case, one thing is clear: As long as each side is determined to achieve its goals on the battlefield, there is little chance of progress in negotiations.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.