A wave of anger passed through Russia after Russian media widely broadcast Ukrainian Acting Foreign Minister Andriy Deshchytsia's obscene comment about President Vladimir Putin, made while attempting to calm a mob attacking the Russian Embassy in Kiev.

But Deshchytsia's comment raised an important question: Why do Russia's neighbors dislike this country so much that they throw stones at the windows of the Russian diplomatic mission?

Of course, such a breach of diplomatic etiquette and unprintable language from the mouth of a neighboring state's senior official is both unethical and unacceptable.

However, Russian politicians and media had already lowered the bar concerning permissible language in discussing key policy issues of the day. Just recall pro-Kremlin television anchor Dmitry Kiselyov's comment about turning the U.S. into atomic dust and his suggestion that the hearts of homosexuals be "buried or burned" if they were to die in an accident.

That is not Moscow's only style of discourse, but it is one of them, and the one that plays a central role in setting officialdom's current tone. And if senior Russian officials feel such forms of expression are appropriate, it is strange that they would take offense when others do the same. To the contrary, they should take pride in the fact that their opinions — and the manner in which they are expressed — obviously carry so much weight.

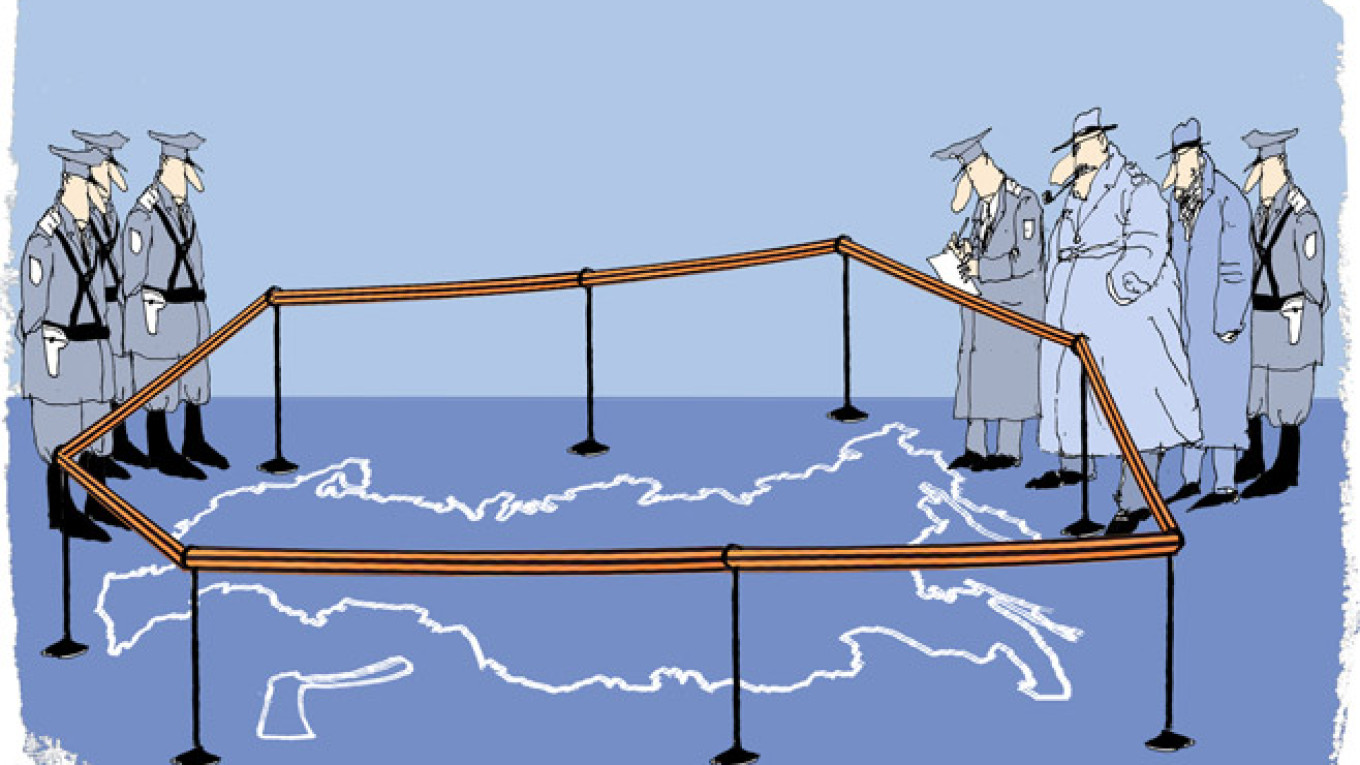

But seriously, the invective that has begun to dominate Russia's discourse with the rest of the world reflects the desperate inability of senior Moscow officials to make others like them.

In today's world, that "reserve of likeability" is no less important than gas and oil reserves or a large nuclear arsenal. Russian politicians have learned that it is called soft power, but they do not fully understand what it means.

I once had a confidential conversation with a Russian official responsible for contacts with the former Soviet republics. He was young, well-educated, thoroughly familiar with the political landscape in each of those countries and demonstrated a strong degree of professional competence.

We finally came to the main point: "Why is it," we pondered, "that those republics are turning away from Russia, one after the other — first Georgia, and now Ukraine?"

"Maybe because Russia does not provide an example that others would want to follow," I answered, with the first thought that came to mind. "We just do not know how to make others like us."

"And how could we get them to like us?" asked the official with the charming arrogance of a person sitting in a small office in the building that once housed the Communist Party's Central Committee.

He apparently thought the former Soviet republics should consider the fact of the great, powerful and wonderful Russia's existence in this world enough reason to continue the long-established tradition of aligning their every thought and move with Moscow's — and with the functionaries in the building of the former Communist Party's Central Committee.

But for others to like you, you must first like yourself — and honestly, Russia has a big problem in this regard. What does Russia have that its own people and others would like — that is, apart from the cheerful young beauties in Moscow's nightclubs for expats?

It seems that state-run television stations have never asked themselves this question either, and we see the results every day. Judging from their programs, the Russian people should like the fact that their grandfathers defeated Nazi Germany and their fathers lived in a country called the Soviet Union — a country that held half of the world in submission and the other half in fear.

That's not much of a choice, though, especially when considering that both values are focused on the past, not the future.

Nor is it so easy to apply those values gained from World War II in everyday life. Practice shows that the more St. George ribbons and other patriotic symbols displayed on an expensive foreign car, the more unpredictably and rudely that driver will behave.

And whereas the government originally intended for World War II veterans to enjoy certain privileges, such as the right to priority service] at medical clinics and other public facilities, self-seeking individuals now use that exception as the basis for corrupt dealings.

Only a true sense of community and well-functioning public institutions — not hysterical television commentators and miles of St. George ribbons — can produce the sense of inner well-being that people seek. When that inner peace exists, others always see it, and that is what makes a person — or a country — an attractive example to others.

It is surprising, of course, that a country that has spent the past 20 years transforming itself into a hydrocarbons trading company is only now starting to think about how to begin liking itself and getting others to like it as well. After all, large corporations always set corporate identity and image-building as key priorities.

Perhaps this is because Russia is less a corporation than a large-scale version of a little rustic kerosene shop whose grumpy vendor names a different price for every buyer, depending on whether he likes the fellow or not.

However, a country with a population of 145 million people cannot be reduced to a simple kerosene shop, and if it wants to survive, it will have to relearn to like itself, and to make itself genuinely attractive to others. It is clearly not enough to bring up memories of the World War II victory that next year will mark its 70th anniversary, or to invoke the Soviet Union, now almost 25 years behind us.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 20 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.