The terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo, a French satirical magazine that very few had heard of before last week but that at this point might well be the most recognizable periodical in existence, unexpectedly highlighted some of the constraints that Russia's increasingly anti-Western rhetoric has placed on its approach to foreign policy.

As is customary after such atrocities, Russian President Vladimir Putin rushed to offer sympathy to the French government and people. The similarity to 9/11, when Putin was famously the very first foreign dignitary to call on U.S. President George W. Bush, is not accidental.

Islamist terrorism is the most significant entry on an ever-shorter list of issues on which Russia and the West are in general agreement. Given the depth to which relations have plunged, it was perfectly understandable that the Kremlin would do its best to remind the West that, whatever its own faults, when it comes to fighting al-Qaida it is in the same foxhole. "Say what you want about us," the argument goes, "at least we're not chopping people's heads off."

It was noteworthy that RT editor-in-chief Margarita Simonyan echoed almost identical sentiments. On Twitter she said that not only would a third world war start in the not too distant future, but that when it does Russia and the West will be fighting together — against whom wasn't made explicit, but the implication was Islamist terrorists.

Compared with the rhetoric about "Western decadence" and "American imperialism" that had been coming out of the Russian government in recent months, this was downright friendly. When one considers both the political sensitivity and the high profile of Simonyan's position it seems logical to assume that "we're all in this together" was a viewpoint that the Kremlin genuinely wanted aired.

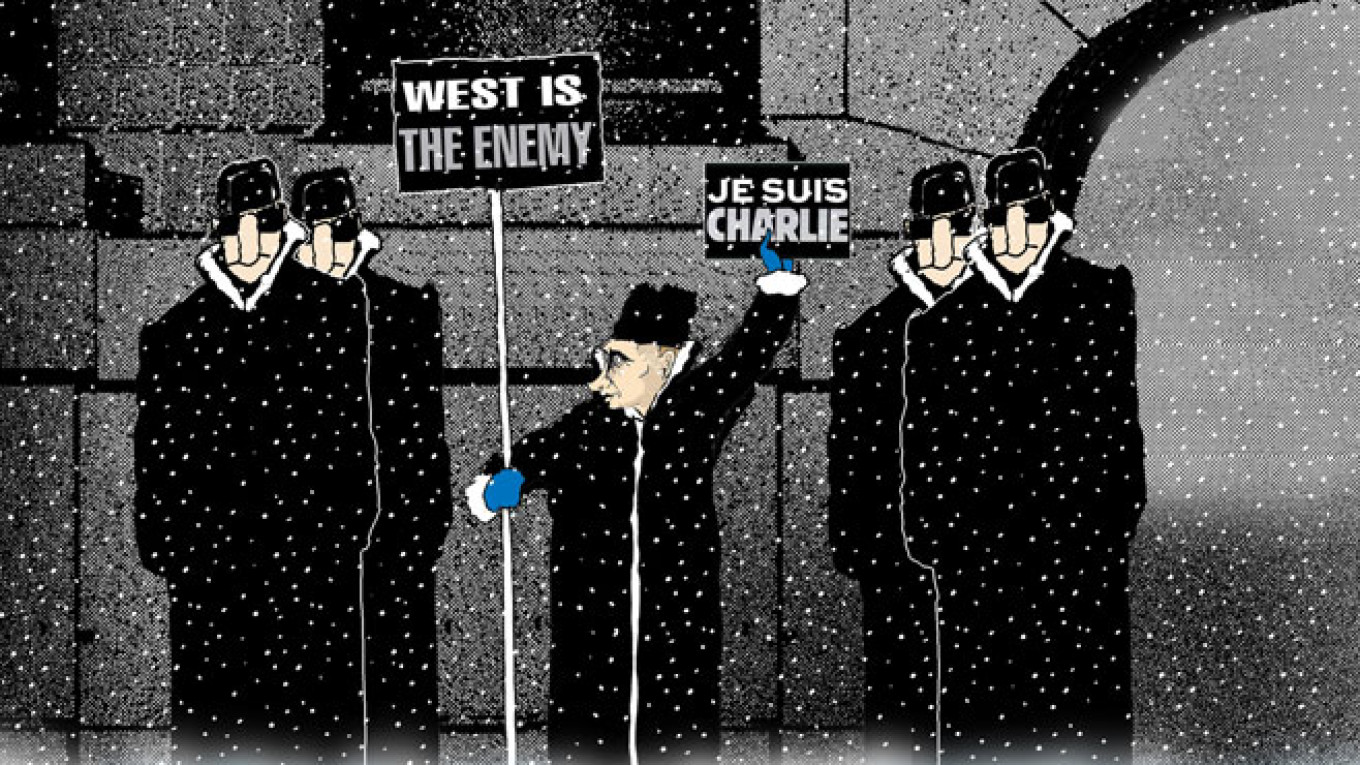

The problem, however, is that over the past year the Kremlin has pressed the "anti-Western rhetoric" button with such reckless abandon that not everyone got the message that the West was Russia's friend once again. Numerous other members of the Russian elite, many of whom were at least as or even better connected than Simonyan, reacted to Charlie Hebdo in a rather less flattering manner.

There was the attempt by LifeNews to argue that the CIA was actually behind the attack in Paris. For them, the Americans are still the root of all problems. There were also of other insinuations in various state-run media that "other forces" were punishing French President Francois Hollande because he had recently spoken out against anti-Russia economic sanctions. These people, too, did not express solidarity with France in the face of Islamist terrorism.

Some of the very loudest voices voicing skepticism about Charlie Hebdo, however, were Orthodox activists who expressed disgust at the magazine's long tradition of viciously mocking religion and the religious. The Orthodox Church made its feelings on free speech very plainly known during the Pussy Riot trial. As an official institution it took the position that religious believers have a right to not be offended by "sacrilegious" speech or acts, and that such acts, by themselves, are worthy of criminal actions. If you accept this intellectual position, you probably are not going to run out and join the people who say #jesuischarlie.

And so even if Putin now wants to quickly pivot and say, "Hey everyone, let's agree both that Ukraine got a little out of hand and that our real enemies are the kind of people who killed all those journalists," his practical ability to do so is extremely limited. Russia has been in the headlines enough recently that even people who don't normally pay much attention to it couldn't help but wonder, "Well, how did they react?"

All kinds of people who never pay any attention to the Russia media were asking about the response to Charlie Hebdo. And much of what they saw, including that ludicrous LifeNews report I mentioned earlier, did not cast Russia in a very flattering light.

The Kremlin, in other words, can have a foreign policy and accompanying media strategy that generally try to play up the country's similarities and common interests with the West — "al-Qaida thinks we're all infidels so we need to stick together" — or it can have a policy that deliberately tries to accentuate the country's unique, Eurasian characteristics — "Europe is decadent, dying and corrupt so we need to aggressively defend Russia's fundamental Christian values." But these are mutually exclusive strategies.

Trying to do both, as Russia is doing at the moment, might at first glance appear savvy or sophisticated, as if Russia has some kind of elaborate scheme that it is skillfully implementing. But it's not. Simultaneously berating the West as a hive of moral degenerates and reminding the West that it is a close ally in the struggle against terrorism is simply a mess of self-contradictory nonsense.

The longer that Russia follows two such diametrically opposed strategies, the greater the risk of total incoherence. That won't make Russia look strong; it won't even make it look weak. It'll just make it look schizophrenic and crazy.

Now it's obviously not up to me to decide which path Russia ought to follow. I would hope it follows the path that tries to downplay its differences with the West, but for political reasons I'm highly skeptical that it will actually do this.

But all actions have consequences, and Russia's anti-Western binge means that it can no longer strike the same notes of comradeship in the aftermath of a high-profile terrorist attack. Putin's pleas of solidarity once found a receptive audience, but that audience is now a lot smaller than it used to be.

Mark Adomanis is an MA/MBA candidate at the University of Pennsylvania's Lauder Institute.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.