Prior to the Russia-Georgia War in 2008, when four regions in the former Soviet space — Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Transdnestr and Nagorno-Karabakh — still lacked official recognition, their leaders would occasionally meet under the informal moniker of the CIS-2. Some refer to the group as the Second Commonwealth of Independent States, others as the First Alliance of Unrecognized States. Either way, the CIS-2 plays an increasingly important role in Russian foreign policy.

On Monday, President Vladimir Putin met with Abkhaz President Raul Khadzhimba in Sochi to sign a bilateral "strategic partnership" and cooperation agreement. Georgia, the United States and NATO quickly stated that they do not recognize the treaty. That is no surprise: They also refused to recognize the first treaty Russia signed with Abkhazia in 2008.

Of course, the new treaty with Abkhazia has attracted more attention because it comes against the backdrop of Russia's annexation of Crimea, the ongoing war in the southern and eastern regions of Ukraine and an unprecedented cooling of relations between Russia and the West. This gives rise to two questions. First, does the new treaty presage Russia's annexation of Abkhazia? Second, has Putin given up on global politics and decided to focus on the zone that Russia still firmly controls?

With regard to the second question, it is not entirely accurate to conclude that following the fiasco at the Group of 20 summit in Brisbane, where nobody but a certain koala bear was happy to see Putin, Moscow has decided to wager on its partnerships with such states as North Korea, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. It is more a question of where Putin will put his priorities in the former Soviet space. Whereas Moscow's relations with many countries in that territory are obviously strained — including with its close allies Kazakhstan and Belarus — with only minor exceptions, Moscow remains the main puppet master in the CIS-2 territories.

The advent of problems in the Donbass has provided Russia with additional puppets — replete with leading characters — for its "theater of operations." Of all the regions where Moscow has a direct interest, so-called Novorossia is the most important and the most populous, despite the fact that a nearly constant stream of refugees has left for Russia and the Ukrainian interior. The proof of its significance: The region has made headlines worldwide for the past six months. At the same time, the Donbass suffers from dire economic problems: The region required major rehabilitation even before hostilities broke out, and now, after a prolonged conflict, it is difficult to imagine not only the cost of rebuilding, but who would agree to pay the bill.

That probably answers the question as to whether Russia plans to annex any more territories like it did Crimea. In all likelihood, no, because Crimea has already placed a heavy burden on the Russian economy such that Moscow now has difficulty funding its own regions. Still, Putin has repeatedly confounded the common sense predictions of experts. Back in August 2008, most of us were convinced that war with Georgia was impossible, and in March 2014 we were equally certain that Putin had no plans to annex Crimea and would shortly order the troops to return home.

If Russia had the same economic resources it had two or three years ago, the partially recognized and unrecognized territories wanting to become part of Russia would have a better chance at achieving their goal. For its part, South Ossetia has been clamoring long and loud to join Russia. Novorossia might go that route, and if it does, it could open up the possibility of a Russian push toward Odessa and change the status of the self-proclaimed republic of Transdnestr.

For that reason, Moldova and its European powers should make the integration question a priority. Although that would not solve the problem of Transdnestr per se, it would add a little stability to the region and make it more difficult for Russia to lay claim to anything beyond Transdnestr itself. And if Transdnestr is effectively removed from the bargaining table, the question of the region serving as a "corridor" would also, at least partly, lose relevance. At the same time, the need to open supply lines to Crimea will constantly prompt Kremlin strategists to want to roll out the tanks.

For their part, Nagorno-Karabakh and Abkhazia never sought inclusion in the Russian Federation. However, the new administration led by former KGB officer Khadzhimba that came to power in Abkhazia this summer is not averse to toning down the cry for the unconditional independence of the region. As any economist would point out, Abkhazia's economy has not improved significantly during its six years as a self-proclaimed republic, and its only hope of growing is to open its market to corporate and private Russian investors.

But Russia, which for obvious reasons has no extra spending money or desire to invest in Abkhazia, is far more interested in the military aspect of the relationship. The creation of a joint Russian-Abkhaz military force under Russian command effectively completes a procedure that Russia began back in 2008 and removes the last formal obstacle to stationing Russian troops in Abkhazia.

Tbilisi definitely views this as a move by Russia to consolidate its occupation of Abkhazia. Moscow sees it as an opportunity to gain a better foothold on the Abkhaz stretch of the Black Sea coast without incurring accusations of aggression and the inevitable sanctions that would follow. A full-fledged base in Abkhazia would enable Russia to support a three-point military presence in the South Caucasus — in Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Armenia — and create the illusion of throwing up a guard wall against Georgia that, despite clearly improved relations with Russia, continues to flirt with the idea of hosting a NATO training center on its territory.

In Nagorno-Karabakh, the problem lies with how Azerbaijan would view any Russian claims on the region. Given the economic and political influence that Baku carries in the South Caucasus, any conflict with that country would clearly ruin any progress Russia might achieve in the region.

In fact, Moscow's decision to shift its attention to the quasi-states of the CIS-2 not only reflects its disillusionment with its neighbors, but also increases those neighbors' distrust of Russia. Nobody wants to be friends with someone who can lay claim to part of their territory at any moment — and then back up those claims with force.

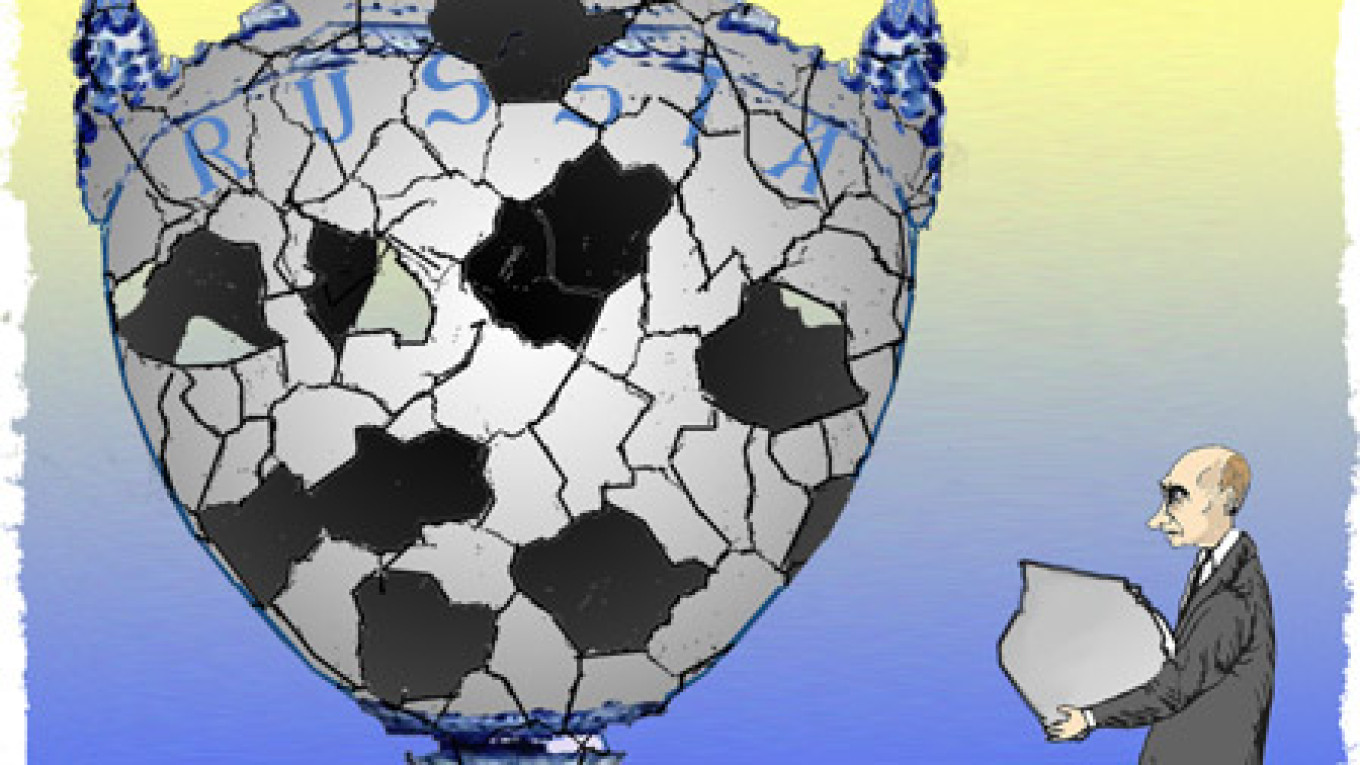

Moscow also runs a certain domestic risk with this policy. On one hand, making Russians feel like members of a united imperialist society by collecting fragments, albeit small ones, of its former possessions has a sort of therapeutic effect on the increasingly fragmented Russian society.

On the other hand, it only fuels long-standing separatist movements in the North Caucasus, Volga region and Siberia, the members of which will inevitably ask: If the Donbass can secede from Ukraine with Moscow's blessing, why can't Tuva, for example, secede from Russia?

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.