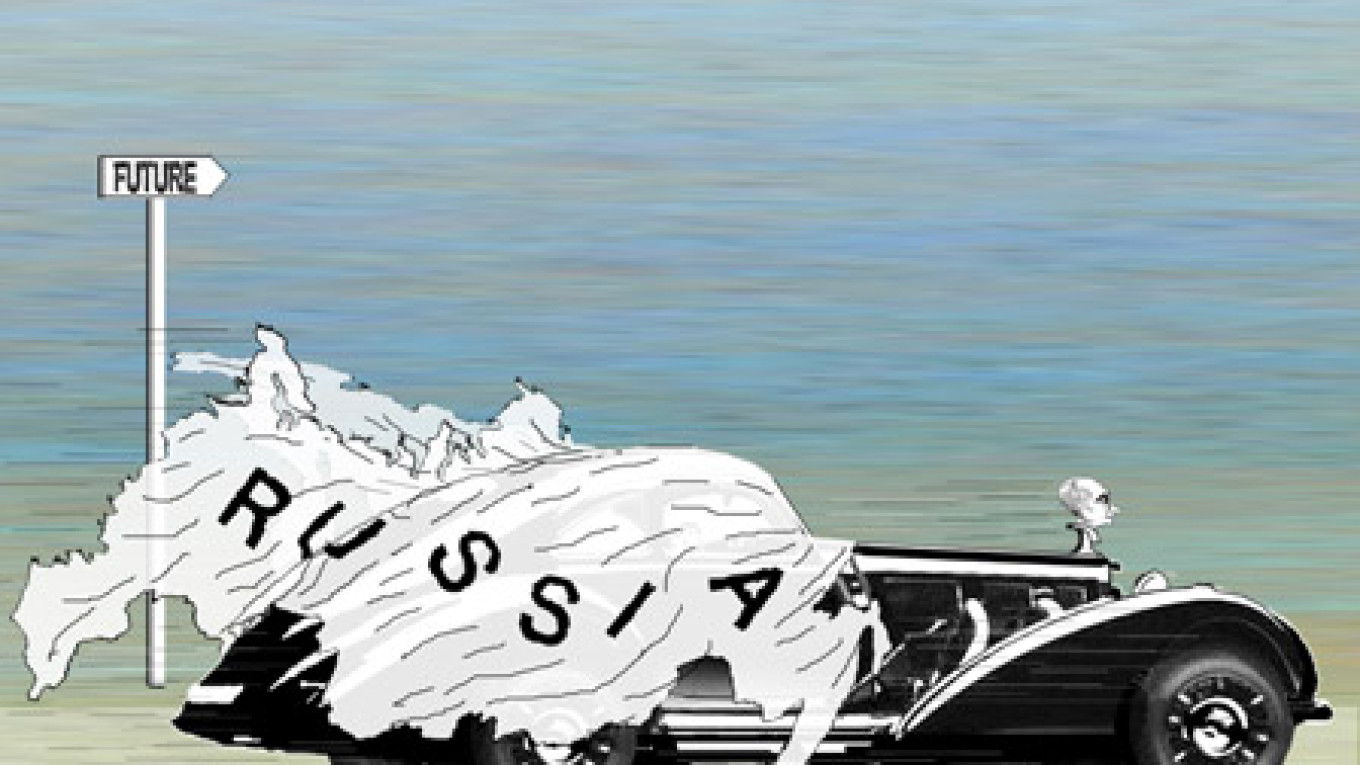

Drivers in Russia often encounter curious road markings. For example, a sign might announce an imminent turnoff for the airport, but in the end, that turn never appears and the driver ends up missing his flight. Perhaps this is because Russia itself is like that driver — whizzing down the highway, searching for and in constant anticipation of an ever elusive turn that will lead him in the desired direction.

Anyone who follows the news in Russia knows that feeling of mounting dread. Monday marked the start of a trial that could put an end to Memorial, Russia's oldest human rights organization. This Friday, the board of directors of Ekho Moskvy is scheduled to meet and very possibly dismiss that radio station's founder and chief editor Alexei Venediktov.

Of course, nobody will keel over and die if Memorial is shut down or Ekho Moskvy goes off the air. But I know masses of people — myself included — who would feel that two very solid bricks were added to the barrier that is slowly and relentlessly walling them in. At the same time, the idea that "masses of people" would suffer is not altogether accurate. Only one in every 10 Russians has even heard of the Memorial human rights organization, and the only thing most people know about Ekho Moskvy radio is that it is critical of the ruling regime.

Modern Russian society has long made fun of Ekho Moskvy listeners, who are largely aging — and in some cases Jewish — Moscow intellectuals. Today's carefree youth only rarely listen to Ekho Moskvy. And if the radio station is closed and its pudgy, poorly dressed listeners take to the wintry streets in protest, they will probably look like a line of Auschwitz prisoners on a forced march.

Of course, the country that "defeated fascism" has no Auschwitz, and the frozen protesters will eventually all return to their homes, but this association with concentration camp inmates inevitably comes to mind every time I hear someone say, "Who listens to that Ekho Moskvy anyway but a bunch of old Jews?" Every such remark thinly veils an underlying fascism that, as it turns out, Russia did not defeat.

For me, real patriotism means joining the line of protesters opposed to the closure of Ekho Moskvy. Or else it means turning out on the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Political Repressions by helping read the endless list of martyrs that the Memorial foundation painstakingly assembled name by name. Of course, such actions do not seem like grand achievements when compared with something really impressive like annexing Crimea.

Again, Russia has no Auschwitz concentration camps, but the mindset of the social ghetto in which we live is already fully formed. Some readers might conclude that everything they have just read here is based on false pathos. After all, the court case against Memorial was postponed until mid-December and human rights activists are certain they can settle all of the complaints of the Justice Ministry by then. And although the government might eventually shutter Ekho Moskvy, for now the station seems to have reached a compromise with shareholders.

Those readers might argue that Moscow has no signs of ghettos and concentration camps, that the Internet works fine and that Muscovites can read, write, buy and sell any books they want, can shoot any movie or watch any film in the theaters and even spend the weekend in Paris if the exchange rate hasn't completely swallowed up their salaries. In short, they say: "Relax, take it easy."

And so what if an occasional event such as the Group of 20 summit in Brisbane makes us wonder whether the president and his millions of supporters are right? After all, Russia is a big country and it is only natural that it feels an irresistible need to remain an empire and consider the states that were once Soviet republics as its lost territories.

And yet every attempt by leaders to offer reasonable arguments in support of their actions ends in more base and insulting lies — such as the comparisons between the situations in Kosovo and Crimea. Or else they come up with new schemes such as linking national identity to the hierarchy of the Russian Orthodox Church — an organization that actually had the audacity to declare: "If you are not Orthodox, you are not Russian."

Each fresh injustice and lie is one more brick in the wall that divides the country in two — into a ghetto whose inhabitants feel a growing sense of foreboding, and the rest, who feel optimistic in their outlook and are convinced that the complainers should "get what's coming to them."

So far, activists have successfully rebounded from every attempt to make nationalistic thinking into official doctrine: Memorial continues to operate, and Venediktov still holds his job. The majority still begrudgingly allows citizens of conscience to read their damned list of victims of Soviet repression under the windows of the Federal Security Service — the respectable successor to the monster that claimed millions of completely innocent lives.

But for every such rebound, there is a new attempt at repression. And it seems as if everyone — all those in the ghetto as well as those outside its walls — are collectively waiting until the final blow is struck and the struggle ceases. At least that would finally settle the question of which path Russia will take into the future.

However, that final resolution never materializes, and it seems to stem from the man behind the wheel. The Russian president cannot help but realize that everything has somehow gone wrong and that he must make some sort of course correction, even if it means openly declaring an inhuman dictatorship. The problem is that he is not alone in the car: He is surrounded by powerful individuals who are perfectly happy with the current state of affairs and have no intention of letting him make any changes whatsoever.

As a result, he finds himself unable to turn the steering wheel to the right or to the left, the car hurtles forward on its road to nowhere, the walls of the ghetto grow taller and wider and the creeping shadows of a resurrected fascism are gathering in the most unexpected of places.

For Russia to have any future at all, the driver must alter his course, turn around completely or at least stop the car and get out to stretch his legs. But as he does none of these, the situation gradually becomes a direct threat to the driver himself. After Brisbane, the driver knows he is completely on his own now, that no one will come to his rescue in the event of a serious accident or an altercation with one of his fellow passengers.

Observers typically believe that Russians solve the problem by simply replacing the driver. However, for the last 15 years, the driver and his fellow travelers — who have all experienced fantastic material gain from their joy ride together — have done everything in their power to make such a change impossible.

Unfortunately, that means Russia will probably not prosper, but neither will it fall into complete disarray. Instead, the driver will probably lose control of his vehicle and smash into the center divider. And after the medics and police are finished at the scene of the accident, the tow truck will come along to haul away the wreckage.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.