Rosneft's transformation into a national super-champion with 20 percent BP ownership establishes a new model for a Russian state company that is likely to have profound consequences for both the country's energy sector and the economy as a whole.

A clue to understanding what some of these might be is the timing of the deal. Why did Russia's leadership give a green light to Rosneft's acquisition of TNK-BP and its strategic alliance with BP now and not 18 months ago? The legal obstacles used by the AAR consortium, the owners of 50 percent of TNK-BP, to stop last year's attempt by BP and Rosneft to buy out AAR could probably have been overcome if then-Prime Minister Vladimir Putin and his close associates had wanted it.

More was at play than just the breakdown of BP's relationship with Alfa Group, one of the three members of AAR.

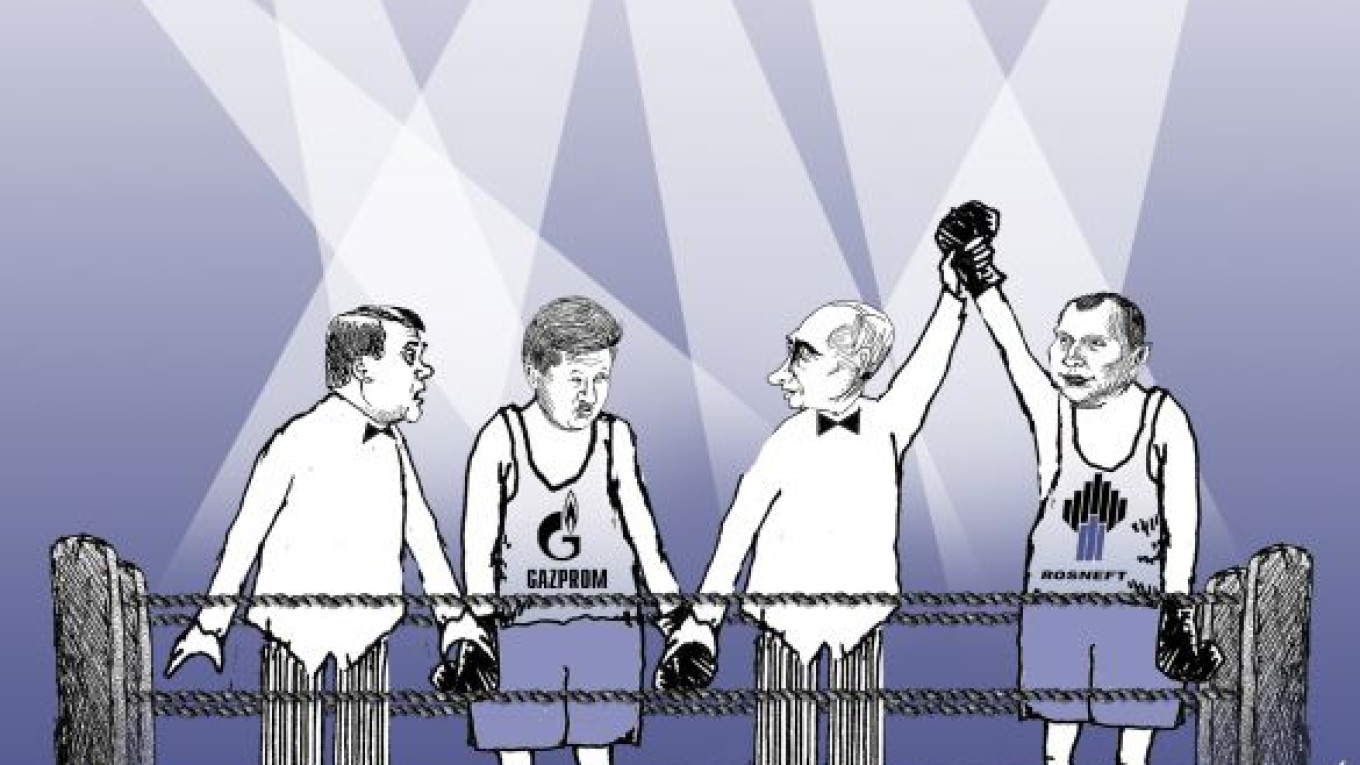

A critical factor that allowed the deal to go ahead this time was Gazprom's demise as a national champion. Its sustained underperformance and lack of responsiveness to the rapidly changing global gas situation brought about by the shale gas revolution are confirmation of a trend that has built up over many years. Gazprom does not currently have the ability to reform itself and adapt to a more competitive environment. Its business model in Europe is coming under increasing strain, and it has so far been unable to diversify to Asian markets.

It is likely that Putin concluded that Gazprom, which until 2008 was a symbol of Russian power and prestige, has become more of a liability. The Kremlin needed to change horses.

A further strong selling point for the deal was the opportunity not just to create a new national champion but to grow it rapidly. This is where BP was needed. BP was hugely successful in creating value at TNK-BP thanks to its disciplined approach to portfolio management and its application of world-class technology and skills. Rosneft has a patchwork of production companies that require integration in a way that was achieved after the merger of BP's and TNK's disparate assets in 2003. Rosneft head Igor Sechin clearly took notice that the value of TNK-BP quadrupled in nine years.

It is not clear at this stage how Rosneft will seek to use BP's expertise, but this will be key to creating long-term value for the company. While critics see the dangers of Rosneft underperforming like Gazprom if it also becomes too large and state-dominated, the decision to give a foreign company a 20 percent stake in a national oil company is unprecedented. Notably, Putin went out of his way to praise BP's performance in Russia when he met Sechin after this week's deal was announced.

Putin said that Rosneft's acquisition was "needed not only for the Russian energy sector but for the entire economy." Although Putin did not give details, it is fair to assume that he was referring to the prospect of Rosneft, with BP's know-how, setting new standards that can be a benchmark for other Russian companies. After all, Putin is well-aware that TNK-BP has outperformed other Russian companies, including Rosneft, by a substantial margin.

Questions remain about the impact of Rosneft's acquisition of TNK-BP on the government's proposed privatization agenda, which includes Rosneft. Some believe that the deal marks the resurrection of state capitalism and a serious blow to the government's former commitment to put more state assets into private hands. At this stage, it is too early to say since privatization efforts have been held up by adverse market conditions. Still, the Kremlin appears committed to privatization as a way of addressing the economy's lack of competitiveness. Rosneft looks like the exception to that rule since BP will become a substantial minority shareholder, and this should help improve Rosneft's operating standards.

Creating a new national super-champion could even put the issue of Gazprom's privatization on the table. The subject was previously taboo because of Gazprom's status as an untouchable national symbol. But now, Rosneft will be the standard bearer of Russia's global energy influence. Referring to the possibility of privatization, Putin said in February that the government would "at some point go over to this so that Gazprom works in a different way." His frustration has clearly been growing with the company's failure to address the increasing pressures it faces in the European market from alternative sources of gas supply. At the very least, a long-overdue change of senior management at Gazprom now looks more likely.

The other interesting aspect of the Rosneft deal is how the extraordinary comeback of Sechin will affect the balance of interests among members of Putin's inner circle, including Gunvor co-owner Gennady Timchenko and the Rotenberg brothers, who have business interests related to the Russian energy industry. Sechin is experiencing a rapid and surprising recovery after it looked like he was on the way out earlier this year. This may now need to be balanced by an allocation of access to new assets to other Kremlin power brokers. Another open question is how far Sechin's influence will extend to other segments of the energy sector.

Finally, the deal has left Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev's team looking bruised and weakened. Both Medvedev and Deputy Prime Minister Arkady Dvorkovich opposed the deal, but they were outmaneuvred by Sechin and overruled by Putin. This defeat could clip the wings of Russia's leading economic liberals and strengthen those who support state capitalism.

The long-awaited TNK-BP denouement has arrived, but the drama is not over. The ultimate consequences of establishing Rosneft as the primary national champion could still be spectacular.

John Lough, who served in TNK-BP's international affairs department from 2003 to 2008, is associate fellow of the Russia & Eurasia Programme at Chatham House in London.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.