People have been asking me all week why the Kremlin is so stubbornly supportive of Syrian President Bashar Assad. "Is Russia's support based solely on weapons contracts with Syria," they wonder, "or the Kremlin's desire to maintain its naval base at the Tartus port?"

Moscow spent the whole week heroically fighting the anti-Syrian tide in the United Nations. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov mustered all his strength to resist the attempt by his Western foes to introduce an Arab League resolution on Syria to the UN Security Council. That prompted the foreign ministers of leading Western states to fly to New York to convince Lavrov of the importance of passing the resolution. Not only did they fail to persuade Lavrov, but he refused to meet with them. Even U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was unable to get a hold of Lavrov the whole day.

In the end, Russia blocked the Security Council resolution that would have called on Assad — who is directly responsible for the deaths of more than 5,000 Syrians — to step down from power. It would have introduced sanctions against the current regime, primarily aimed at halting weapons deliveries to Syria. But Moscow fought in defense of its friend Assad, arguing that the resolution would open the way to foreign military intervention a la Libya.

A Russian vessel chartered by Rosoboronexport, the state arms exporter, recently docked at a Syrian port and, according to Western reports, delivered 60 tons of ammunition to Assad's security forces. Are Russian leaders really unaware that such actions discredit them in the eyes of the world community? Are they incapable of understanding that if the opposition comes to power in Syria, Russia's ardent pro-Assad policy will mean that Russia will be on Syria's "blacklist" for many years to come?

Of course, it could be argued that Syria has been a large, loyal buyer of Russian weapons systems since 1970. Syria only recently signed a $500 million contract for the delivery of 36 Yak-130 trainer combat aircraft. Before that, Syria took delivery of Russia's cutting-edge Bastion missile system for defending its coastline, along with anti-tank systems — a few of which ended up in the hands of Hezbollah. What's more, Russia is currently fulfilling an order to modernize armored vehicles it sold to Syria in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Assad regime also gave Moscow its only military base in the Mediterranean, although it remains a mystery to me what military value the base offers the Kremlin.

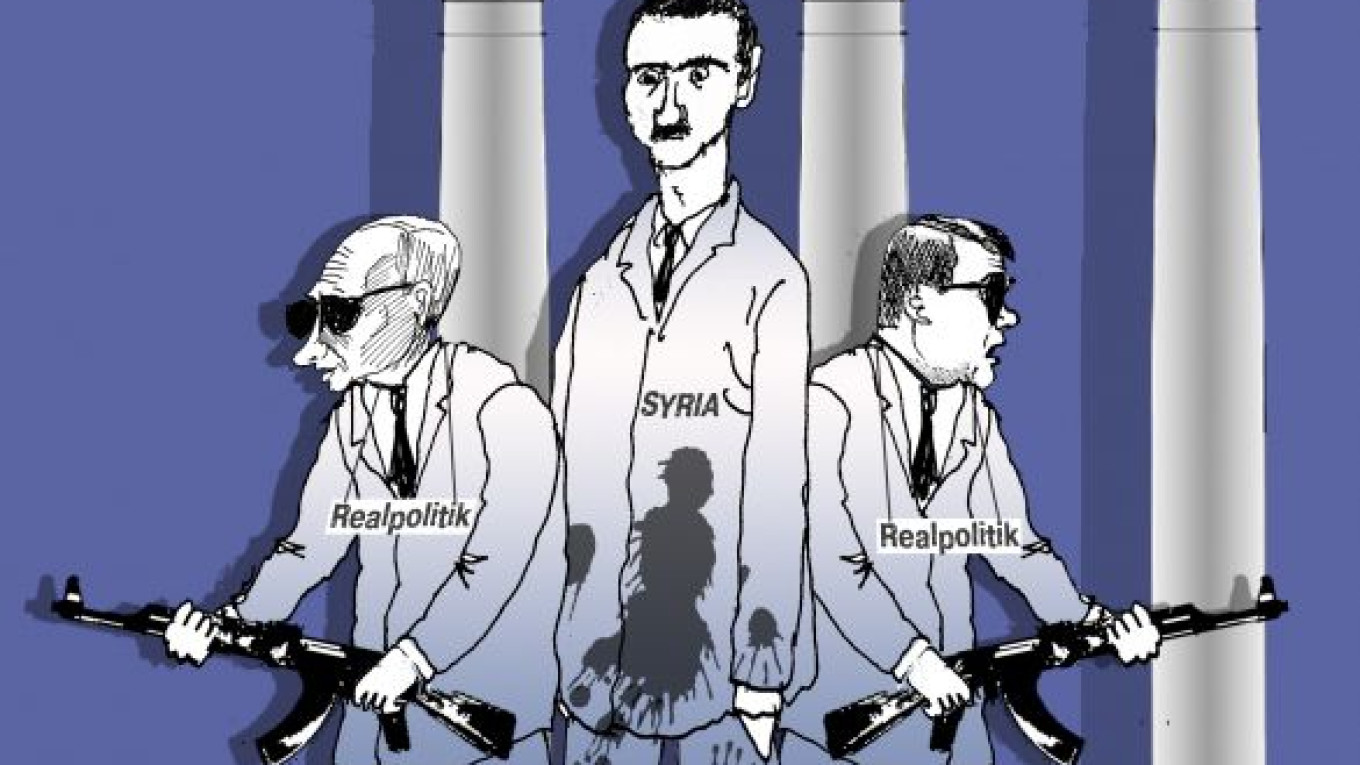

I have often written that Russian foreign policy is guided by 19th-century realpolitik. It boils down to the much-quoted postulate that there are no eternal allies — only eternal interests. And this is where Moscow refused to budge. With so many vested interests in Syria, Russia is prepared to defend Assad to the very end.

This is not a question of geopolitics, but something else completely. Kremlin leaders are paranoid about a "color revolution" in Russia, in contrast to their simulated concerns over U.S. missile defense plans, which they understand does not pose a threat to the country's nuclear deterrence. Russia's leaders are prepared to battle the "orange plague" wherever it appears in the world. The Americans executed regime change in Iraq and Libya. Now they want the same in Syria — and are planning the same for Russia.

But what is so foolish about Russia's pro-Assad policy is that even if the Kremlin supported the Security Council resolution and the Syrian opposition forces replaced Assad, Russia's military base would doubtless remain intact along with some of the current weapons contracts.

Instead, Russian leaders have dug in their heels. That means that their fears of a color revolution is trumping every other rational consideration. Undoubtedly, the events that unfolded in Libya also played a role in their position. Russian leaders feel they were "duped" by the West after they gave the green light to the resolution against Libya. The occupants of the Kremlin had thought that by supporting that resolution, they could drag the West into a series of lengthy negotiations that would convince everyone that Moscow is still a major power in the global arena. Instead, Western governments began their air assault on Libya and pushed Russia out of the decision-making process.

Now Moscow is taking revenge for that slight by creating obstacles to a reasonable, much-needed UN resolution on Syria. Russia aims to block any more military interventions, but none will be needed because Assad's regime will eventually be overthrown. That will leave Moscow mourning its lost influence in the region as well as the end of its lucrative military contracts. Thus, Putin's realpolitik has finally lost its most important attribute — realism.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.