Russia's military intervention in Syria has firmly supplanted Ukraine in news headlines and Kremlin propaganda. That seems to even be reflected in the way President Vladimir Putin conducted himself during the recent "Normandy Four" meeting in Paris. The Russian president behaved differently in Paris than he did in Minsk in February. It is possible he has grown "bored" with Ukraine: nothing new is happening there. Syria is his new priority.

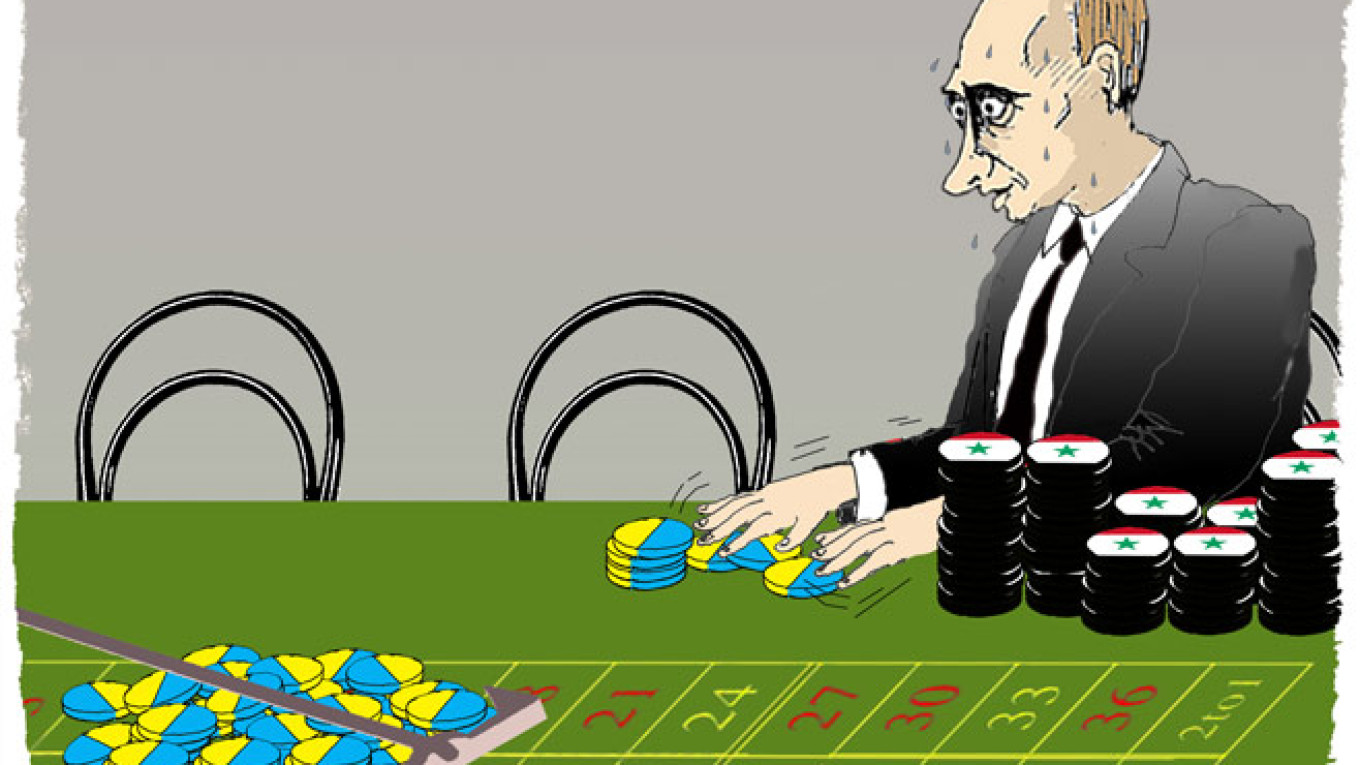

By joining the war in Syria, Moscow used the same psychological trick it played repeatedly in Ukraine over the last year: it raised the stakes, forcing its international partners to wonder what the Kremlin schemers are up to and what their next stunt would be. There are more "chips" on the table now — both Ukrainian and Syrian.

The first crisis remains far from resolution and the second threatens to escalate. What's more, the second crisis involves far more players than the first, each of whom is pursuing their own interests.

However, Putin seems at ease with this type of situation: he has repeatedly proven himself a worthy tactician. He evinces cool confidence even as the ambitious and domineering Turkish President Recep Erdogan warns of worsening relations or as threats pour out from the capitals of Sunni monarchies led by Riyadh. What does that indicate — cold-blooded calculation or indifference born of despair over the fact that things could not get any worse anyway, so why not take a chance?

With Syria now at the fore, has the Kremlin surrendered Novorossia? That project did not pan out as planned back in the spring of 2014. Novorossia does not stretch from Odessa to Crimea, Ukraine did not break into pieces and, unexpectedly for many Russians, the "junta" in Kiev proved tenacious.

And almost overnight, the dramatic television news reports of Ukraine disappeared without Russian society even missing them. The Russian people are tired of the Bandera motif. And the ultra-patriots were wrong in their prediction that masses of Russians would express disappointment in the Kremlin if it abandoned Novorossia. They didn't.

At the same time, many of Moscow's goals in Ukraine, if not yet realized, remain achievable. In this sense, the Novorossia project partially succeeded. The price of that success is another question: it proved to be quite high. But now Moscow can use the Donbass as leverage against the authorities in Kiev for a long time to come. Europe has already mentally come to terms with Crimea's departure from Ukraine. And of course, that whole episode will be seen as a victory for the Kremlin, even if decades pass before Russian Crimea receives legal recognition.

Although no Western capital would openly admit it, Ukraine's accession to NATO has been postponed indefinitely. That can also be considered a partial success of the Novorossia project — that is, if NATO expansion is seen as a threat to Russia. And it confirms another principle of international politics taken from the field of psychology — namely, that the more outrageously a country behaves, the more influence it has. The West might not invite the world's weirdest leaders — such as North Korean leader Kim Jong Un — to summits, but it is also careful to avoid upsetting them unnecessarily.

Similarly, the West will wait a good long time before it crosses Russia again with the question of Ukraine's accession to NATO. That would only change if Russia's economy were to deteriorate so badly that the country required outside assistance. But that day is far off. The Russian people have great inertia, and even greater patience.

Russians have said they are willing to pay the price for Crimea and the Donbass. Well, they have paid, and are paying a high price for the conflict in Ukraine. The Russian economy continues to worsen not only due to the low price of oil, but as a result of Russia's growing international isolation and a paralysis of will on the part of leaders to do anything about it.

The Russian people are paying for the fact that leaders have almost wholly substituted their foreign agenda for attention to the domestic agenda. The Kremlin has suddenly become obsessed with its foreign policy agenda, even while telling citizens at home to "sit tight and wait for oil prices to rebound."

But then, nobody is exactly complaining, either. The joy of watching television broadcasts of glorious military victories mitigates the grief over the family's shrinking budget. And that is nothing new for Russians. In this country, the state is always more important than the individual.

One of those rare "fifth column" critics of the regime might point out that many soldiers are bound to come home in coffins. But only their immediate families will grieve: that is how it has always been. For now, polls indicate that more than two-thirds of the Russian people approve of the military intervention in Syria. After all, how many allies can Russia just "hand over to the West" — no matter who those allies might be?

In this sense, Moscow has not abandoned its Novorossia project, but consolidated its victories there and launched its own reset, creating the New Syria project. The goal is the same: Russia is fighting for its national pride, as Russia alone understands it. And that emotion is personified in a single man who, no matter what he does, remains the undisputed and uncontested authority for the majority of the population.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.