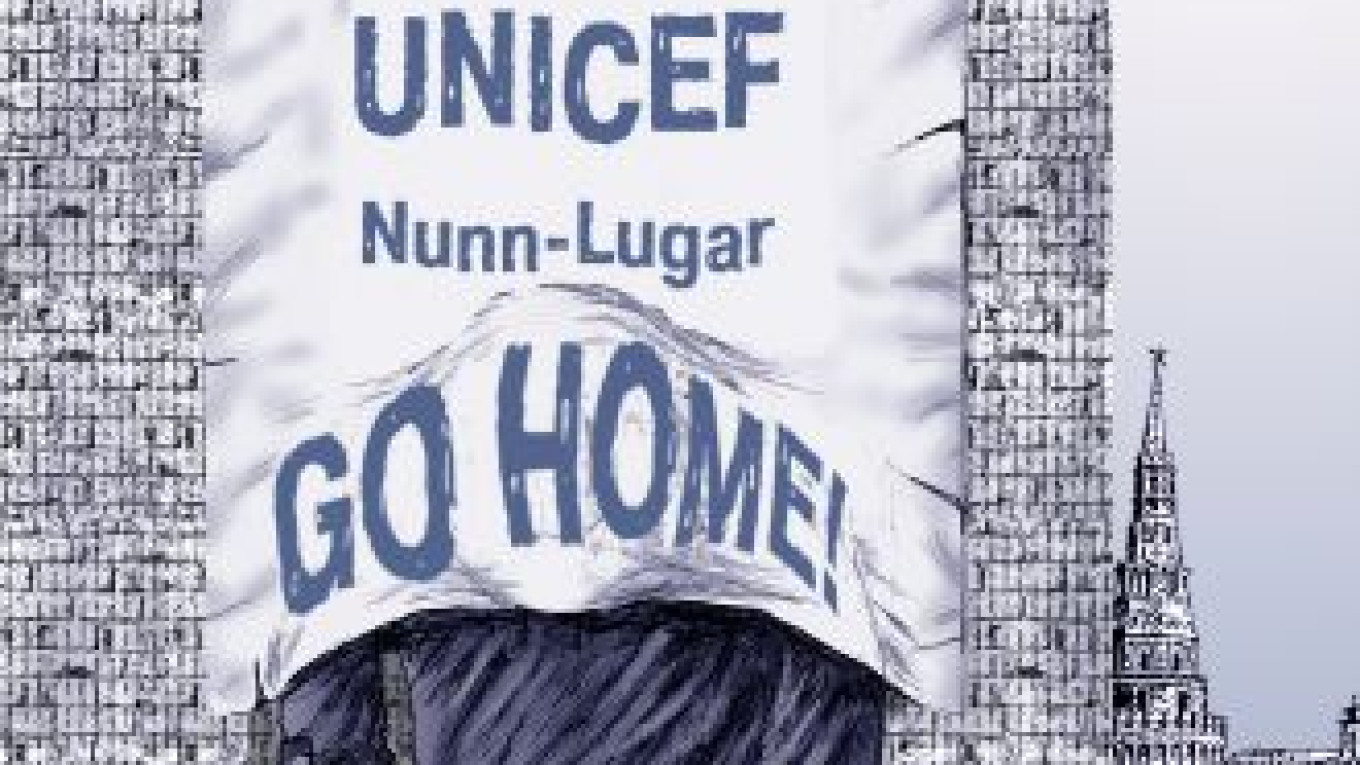

First, the Foreign Ministry announced that USAID must leave Russia by Oct. 1. Then, early last week, the ministry said UNICEF, the United Nations children’s agency, must wrap up its existing programs by the end of the year. Several days later, the ministry announced that Russia will discontinue its participation in the U.S.-funded Nunn-Lugar program, which over the past 20 years spent $8 billion to help Russia dismantle and destroy its extraneous nuclear missiles, warheads and submarines as well as old stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons.

In all three demarches, the Kremlin has sent a clear message to the United States: Russia no longer needs U.S. help because President Vladimir Putin has turned the country into a self-sufficient global power.

But has he?

Several key statistics paint a different picture:

- Russia has nearly 800,000 children in state institutions, placing it No. 1 in the world in terms of number of orphans per 10,000 citizens, according to journalist and Public Chamber member Nikolai Svanidze.

- The World Bank says Russia has 700,000 to 1.5 million HIV-positive citizens and one of the ?fastest-growing HIV-infection rates in the world. More than 85,000 Russians died from AIDS-?related diseases in 2011, according to the government’s Federal AIDS Center, a rate roughly three times higher than the average in Europe.

- More than 20,000 Russians died from tuberculosis in 2011.

- Russia’s 14 million disabled people face institutional discrimination, social ostracism and neglect and have few opportunities to integrate into society.

USAID and UNICEF have spent hundreds of millions of dollars during their 20 years in Russia to assist people from these groups. Now, much of this money will disappear. Equally alarming, in March, the Kremlin turned down $127 million from the Geneva-based Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Russia’s national pride apparently has no price tag.

Although Moscow has promised to fill at least part of the financing gap, these sectors will likely remain neglected as the Kremlin continues to give preference to financing law enforcement agencies, the Federal Security Service and the military.

One of the myths behind Putin’s ideology is that under his rule, Russia has risen from the poverty, chaos and backwardness of the 1990s. But a visit to a Russian orphanage, a specialized clinic for HIV or tuberculosis patients, a retirement home or even a typical outpatient clinic in a provincial town is enough to see that very little has changed since the chaotic, bankrupt 1990s that Putin is so fond of cursing.

But what about nuclear weapons, which, unlike orphans and the disabled, have always been a top priority for the government? The Defense Ministry would need to allocate about $400 million a year to continue destroying the large supply of remaining weapons of mass destruction after the Nunn-Lugar agreement expires in May.

Yet Russian hawks might argue that these funds would be better spent on upgrading the current nuclear arsenal as part of the country’s ambitious weapons-modernization program, which Putin announced last year. Moreover, some generals could insist that it is better to maintain the country’s old, nondeployed nuclear warheads and missiles as a bargaining chip against the U.S., or as a reserve that could, in theory, be activated if Russia decides to pull out of its disarmament treaties.

In addition, Russia’s decision on Nunn-Lugar is blow to both the “reset” and U.S. President Barack Obama’s broader global program of nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation. Nunn-Lugar was considered one of the most successful and farsighted U.S. foreign policy initiatives since the Soviet collapse. The program also represented the apogee in U.S.-Russian cooperation as it built trust between the two sides, increased transparency and improved global security by controlling the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction to hostile countries and terrorist groups.

Unfortunately, Russian authorities, as if they went out of their way to refute the achievements of Nunn-Lugar, said one of the reasons they are walking away from the program is their concern that the country’s nuclear secrets might be revealed. Just like with USAID, the Kremlin was suggesting that Washington is using aid programs as a cover to carry out spy missions and undermine Russia’s national security.

The Kremlin’s latest decisions has sparked pessimism that Russia is constructing a new iron curtain of sorts to isolate itself from international assistance programs. But perhaps not all is lost. Russia is negotiating with the United States and the UN on amending the Nunn-Lugar and UNICEF agreements. The goal is to develop a new approach that will allow the Kremlin to save face by minimizing the West’s role as a donor and Russia’s role as a recipient — something Moscow finds demeaning and unfittting for a country that claims to be a global leader and one that boasts of being a donor to other countries. As for USAID, perhaps it can find a mechanism suitable to the Kremlin that allows the agency to fund charitable and social-oriented Russian NGOs directly from Washington.

The United States should do everything it can to placate the Russians’ wounded pride by repackaging Nunn-Lugar, USAID and other international assistance agreements while keeping their core objectives intact. The stakes are too high for everyone.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.