The Pussy Riot case has stirred up the international community even more than Russian society, seizing the headlines in major media. In Russia, the greatest interest in the case came from residents of Moscow and St. Petersburg, as well as political and religious activists. Nonetheless, the case reveals as much about the nature of Russian politics as it does about Russia's problems with foreign policy and its image abroad.

The case of the now-famous punk group has conclusively proven to the world that Russia is an authoritarian country led by President-cum-dictator Vladimir Putin and an active repressor not only of the political opposition, but also of freedom of expression and creativity.

What's more, the support shown for Pussy Riot by prominent celebrities such as Madonna, Paul McCartney, Sting and Bjork focused unanticipated international attention on Russia. In contrast to the more ambiguous Yukos affair, in which Putin & Co. at least partially succeeded in convincing the world that former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky was guilty of tax evasion, the circumstances surrounding the Pussy Riot case were obvious to any outside observer. What in any Western country would be considered a misdemeanor ended in Russia with an excessively severe two-year prison sentence. The reaction of the Russian authorities fails to show the necessary tolerance of the state and society toward nonconformist art, and it contradicts the practices of democratic countries in such situations.

The verdict against Pussy Riot significantly damages the reputation of both Russia and Putin, who is widely viewed as having personally ordered the sentence. In addition, clumsy attempts by the Foreign Ministry to justify the verdict by claiming that it corresponds to legal measures in Western states have only exacerbated the awkwardness of the case — especially because the ministry has been unable to find a single such example.

So who really ordered the harsh sentence against the three Pussy Riot members — the Kremlin or the Russian Orthodox Church? The day after the verdict was handed down, the church urged the government to "show mercy," a sentiment that was conspicuously absent prior to the sentencing. In this way, church leadership tried to carefully distance itself from a verdict that has already disillusioned many believers, especially intellectuals in larger cities.

Of course, the decision for the punishment was not made by church leaders but by the Kremlin. The authorities only used the Russian Orthodox Church as a cover, citing the offended feelings of believers to justify its actions. In fact, the tough-fisted verdict is just part of Putin's larger aggressive policy that began on May 6 and 7 with the crackdown on the Bolotnaya Ploshchad mass demonstration and the decision to clear the city streets of people for his inauguration motorcade.

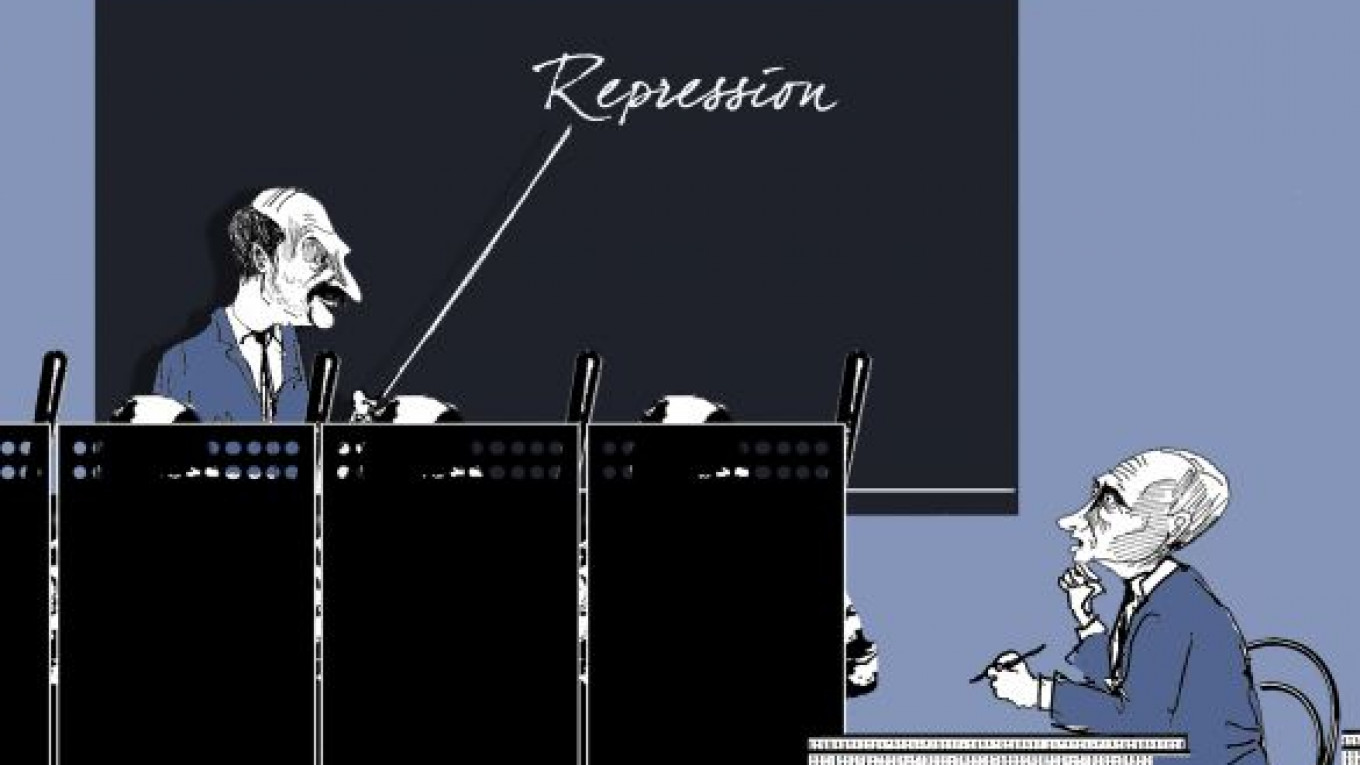

Everything that has been happening in the country in recent months is a result of Putin's reaction to the mass protests staged between December 2011 and May of this year. The regime responded soon after Putin's third presidential inauguration by adding draconian laws to the Criminal Code — laws limiting public protests, forcing NGOs to register as "foreign agents," permitting censorship of the Internet and recriminalizing slander and libel. Now the first stiff sentences have been handed down in the new Putin era — one that will be marked by greater repressive measures and bitterness.

Putin's goal is to intimidate the dissenting members of society and to frighten the growing wave of protesters into submission.

In his approach, Putin is emulating Belarussian dictator Alexander Lukashenko. Putin believes he will be able to keep society's dissatisfaction under control indefinitely if, like Lukashenko, he beefs up his security forces by giving them extraordinary powers, openly persecutes the opposition and dissenters, censors the Internet and passes laws regulating protest rallies.

Not only the threat of repression, but actual repression is necessary to effectively intimidate society. Putin has made Pussy Riot the first political prisoners of his new term in order to intimidate others. What's more, the irreverent young women made it easy for Putin to rally the conservative and patriarchal members of society against the "defilers" — liberals and members of the opposition and creative intelligentsia. Putin is not only unafraid of schisms forming in society, but he also is actively fomenting and exploiting them for his own political purposes.

Putin understands that the cost of stepping up repression at home will be growing isolation abroad and, possibly, Western sanctions against officials implicated in human rights violations and corrupt dealings. And so, in true Belarussian style, Putin is preparing to pass legislation banning state employees and corporations from owning property and bank accounts abroad.

Putin seems to have purely personal motives in punishing the Pussy Riot members. The group had previously staged several high-profile anti-Putin stunts prior to the incident at Christ the Savior Cathedral. Federal guards detained the women after one such stunt on Jan. 20 in Red Square titled "Putin [expletive] His Pants." Now Putin has gotten his revenge: two years in a penal colony for the offenders.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, hosts a political talk show on Ekho Moskvy radio and is a co-founder of the opposition Party of People's Freedom.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.