Comments by Prime Minister Vladimir Putin in late December must have come as an unwelcome surprise to Presidents Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev as they try to conclude a new U.S.-Russian arms control agreement to replace the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or START, that expired on Dec. 5.

But this was not the first time that Putin has thrown cold water on Medvedev’s efforts. In June, Putin stunned Medvedev and leaders in the West by announcing a change in Russia’s approach to pursuing membership in the World Trade Organization just when everyone thought that Russia was about to cross the WTO finish line. In both cases, Putin reminded Medvedev and the international community that if you want to get things done, it isn’t good enough to just have the Russian president on board. The prime minister has virtual veto power.

The latest problems arose following a meeting between Medvedev and Obama in Copenhagen on Dec. 18. They announced that their negotiators were close to reaching agreement on the START replacement treaty. Despite last-minute snags and sticking points over inspections and telemetry, both sides expected to finalize the agreement early in 2010 — that is, until Putin opened his mouth on Dec. 29 while on a visit to Vladivostok. Asked by a journalist to name the biggest obstacle to reaching agreement on the arms control treaty, Putin responded, “The problem is that our American partners are building an anti-missile shield and we are not building one.”

This wasn’t the first time that Putin has tried to throw a monkey wrench into Medvedev’s efforts to finalize major agreements. During the St. Petersburg economic forum in June, where Medvedev was the main feature, the talk among Russian officials and international visitors was about Russia’s imminent membership in the WTO. Until that time, Russia remained the largest economy outside of the organization. But after extensive negotiations, U.S. Trade Representative Ron Kirk and other trade officials present in St. Petersburg were speaking more positively than ever about Russia being on the verge of ending its exclusion from the WTO.

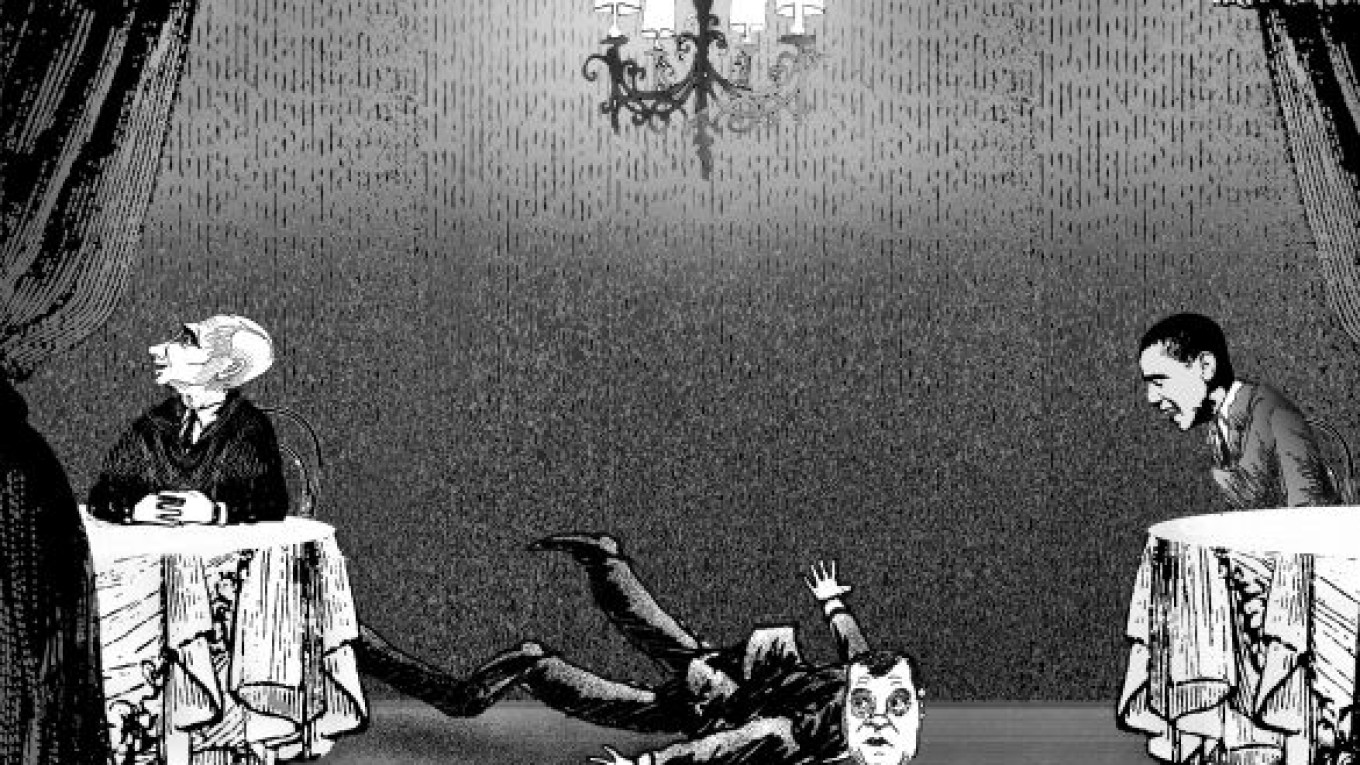

But then within days after we heard these optimistic statements, Putin pulled the rug out from under Medvedev by announcing that Russia would seek membership in the WTO only in union with Kazakhstan and Belarus. Putin’s announcement came as a complete surprise to everyone, including those in his own government, and derailed a deal that finally had seemed to be within reach of Russia after many years of trying. Moreover, Putin had the temerity to blame the United States for blocking Russia’s WTO membership when he himself is responsible.

Depriving Medvedev of victories seems to have become an objective for Putin. This is a reflection of Putin’s deep sense of insecurity and manifests itself when he competes with Medvedev for global attention and glory. During his eight years as president, Putin failed to achieve membership in the WTO, while it appeared that Medvedev was close to reaching that goal at the start of his second year in office. Similarly, signing an arms control agreement with the United States would have marked another accomplishment for Medvedev and an early milestone in the “reset” in U.S.-Russian relations. It seemed that Putin feared that Medvedev could show him up in one of the most important areas in global affairs — nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation.

Beyond raining on Medvedev’s parade, Putin also seems intent on maintaining hardline positions on issues of importance to the United States, including sanctions against Iran. In contrast to Medvedev’s seemingly open position on sanctions, Putin has repeatedly made clear his opposition to getting tougher with the Iranian regime. Is Putin weighing in on the hopes of exacting last-minute compromises from the United States, assuming that Obama is desperate to get an agreement signed and might be willing to make key concessions to Russia? Perhaps Putin is intent on blocking the reset in bilateral relations because he needs to maintain the image of the United States as a “threat” to Russia to justify his autocratic vertical power structure.

Whatever the explanation, the U.S. State Department responded correctly to Putin’s year-end salvo in Vladivostok by flatly rejecting a link between post-START negotiations and missile defense. Maintaining a firm stand against provocations and bullying from Putin is exactly the right response. At the same time, the Obama administration should resist getting drawn into a corner in which it is forced to make a choice between Medvedev and Putin as “most-favored negotiating partner.” It would be a mistake to assume that Medvedev would be more amenable than Putin to improving relations. Obama already made that mistake last summer when, on the eve of the summit with Medvedev, he made a sharp remark that Putin has “one foot in the old [Cold War] ways of doing business.”

For the reset in U.S.-Russian relations to succeed, both Moscow and Washington must show interest in working together. Medvedev might be interested in this, but from all appearances Putin — the real power in the Kremlin — is not.

David J. Kramer is a senior trans-Atlantic fellow with the German Marshall Fund of the United States. He served as a deputy assistant secretary of state responsible for Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova during the administration of former U.S. President George W. Bush. The views expressed by the author are his own.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.