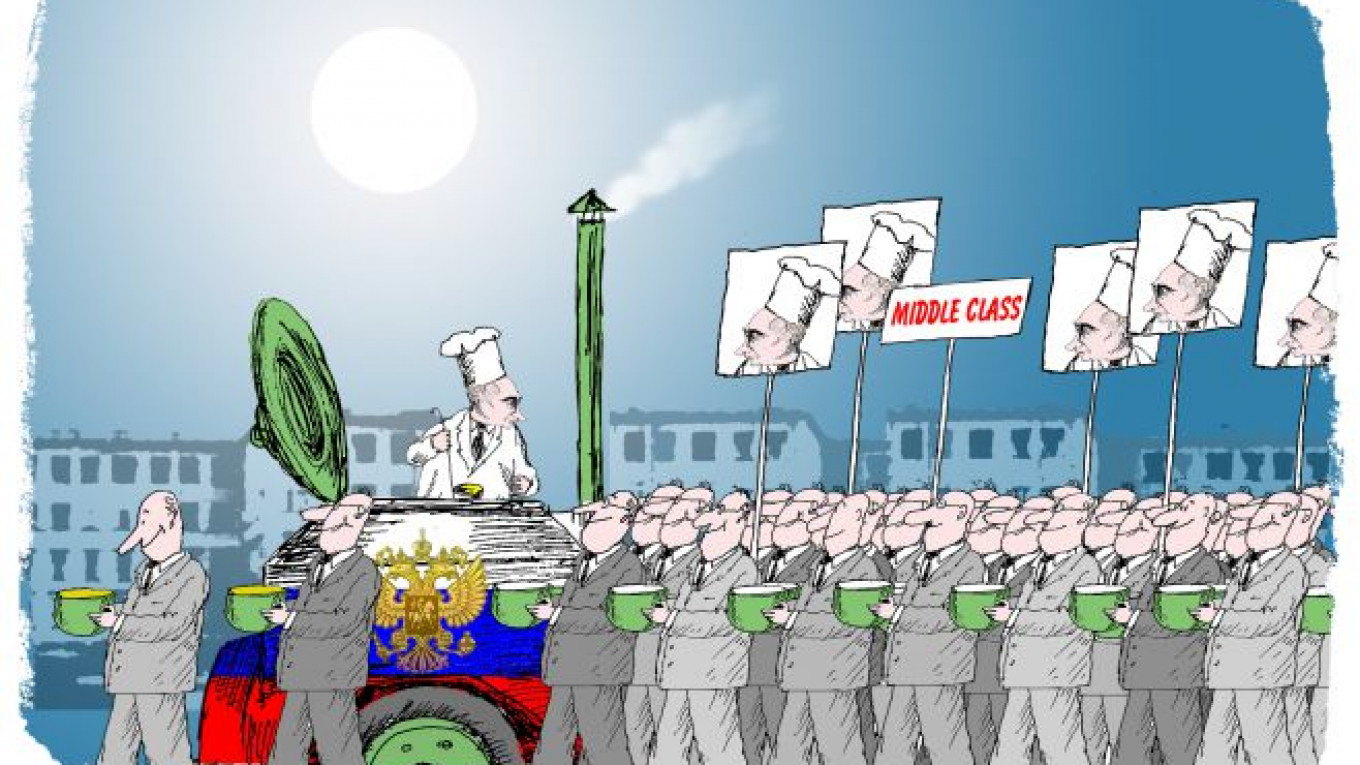

The middle class is the mainstay of Russia's society, as well as the greatest threat to the country's political regime.

The Russian middle class is conservative, prefers stability to change and generally supports the ruling authorities. However, the Russian middle class is also accustomed to its relatively comfortable position, and to its high — by Russian standards — level of consumption. Its members expect the government to guarantee their income and provide free education and health care. If access to those benefits disappears, the middle class will unhesitatingly cease to support the authorities.

These conclusions are based on a major study conducted by the Russian Academy of Sciences' Sociology Institute (ISRAS) and titled "The Middle Class in Russia — 10 Years On." The study analyzed data from a survey of more than 2,000 Russians from all regions of the country and compared them with similar research conducted in 2004.

According to the recent report, the Russian middle class now accounts for 42 percent of the population — the first time in post-Soviet history that it has surpassed the 40 percent mark. However, it differs significantly from Western countries in that the majority of Russia's middle-class citizens are employed by the state and not by private companies.

According to the Economic Development Ministry, last year the public sector accounted for 50 percent of the Russian economy and, according to the State Statistics Service, employed 25.7 percent of all economically active citizens, up from 24.6 percent in 2009. That is 19 million people, a significant number of whom comprise Russia's middle class.

President Vladimir Putin received about 46 million votes in the 2012 presidential elections. The core of that electorate is composed of state employees who essentially voted for Putin as a kindly employer. State officials at all levels are especially pleased by the fact that their salaries are two to three times higher than the national average, and they receive pay increases two to three times faster than other citizens.

And to make sure those rank-and-file state employers remain satisfied, Deputy Prime Minister Olga Golodets has promised that salaries for doctors, teachers, librarians and social workers will grow 1.4 to 1.5 times faster than the average.

Immediately after returning to the presidency in 2012, Vladimir Putin signed the "May decrees," which strengthen support from his main social base by requiring annual salary increases for state employees. However, they simultaneously place an enormous burden on local and regional budgets that are already staggering under a cumulative debt of almost 2 trillion rubles ($60 billion). In 2013, salaries for doctors, teachers, college professors, scientists and social and cultural workers rose 10 percent in less than a year, surpassing 30,000 rubles ($880) per month for the first time.

Russian state-owned companies and corporations also offer significantly higher-than-average salaries. In fact, former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin recently proposed a three-year salary freeze on all state corporations, including Gazprom, to reduce the burden that those monopolies place on the national economy.

The nearly 20 million state employees are better off than the great majority of their fellow citizens and comprise the main beneficiaries of the current socio-political and socio-economic system.

According to research by ISRAS, the middle class is the most content segment of modern Russia's population: 61 percent of its members, or 16 percent of the total population, enjoy their jobs. About 78 percent favor stability, and only 22 percent want change. Almost 40 percent of the Russian middle class perceives no problems at all, agreeing with the statement that "their lives are turning out well."

Happy with their condition and not desiring any significant change, Russia's middle class is content to follow the course set by the authorities. The middle class has opted to reject Western values and believes that it is better if Russia follows a unique path toward development.

The portion of the middle class that supports the Western model has fallen in recent years to a third, and that number is even lower among other segments of the population. According to their thinking, the interests of the state and society outweigh the interests of individuals, and the role of the political opposition is to help the authorities, not criticize them. In line with those beliefs, Russia's middle class has completely accepted the official version of events in Ukraine.

The Russian middle class has grown up in a society dominated by political and economic monopolies, and as a result, has developed both a monopolistic lifestyle and habits. Sociologists note that average Russians are losing interest in developing their own human capital — that is, their knowledge base and professional skills, along with the practice of reading books and periodicals. They are securely established in monopolistic jobs and, with very few opportunities to advance in their careers, see no reason to improve.

Of the 60 million Russians that ISRAS identifies as Russia's middle class, 22.7 million are the stable "core" that never declines in wealth, even in times of crisis. The remaining 37.3 million are the poorer "periphery" of the middle class that consists of state employees, low-level officials, ordinary workers at state-owned enterprises as well as those working in trade and other services. That latter group rapidly loses its numbers during socio-economic crises.

Thus, the middle class shrunk dramatically during the financial crisis of 2008-09. As a result, ratings plummeted for Putin and United Russia, culminating in the mass protests from winter to spring of 2011-12. The way to the middle class's heart is through their stomachs and wallets, their customary standard of living and consumption.

The loyal and conservative Russian middle class is a product of and pillar for the ruling bureaucracy and monopolistic state capitalism, but only as long as that bureaucracy and state capitalism keep it well fed.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, is a political analyst.A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.