The St. Petersburg International Economic Forum’s agenda reflects Russia’s dual position of being part of both the East and the West. Russia is the only developing country in the Group of Eight. It is also the only G8 member among developing countries. Russia is the fastest- growing economy in Europe but the slowest-growing economy among the BRICs. Therefore, it is not surprising that the discussions in the St. Petersburg forum will focus on the issues of both the developed countries and the emerging markets.

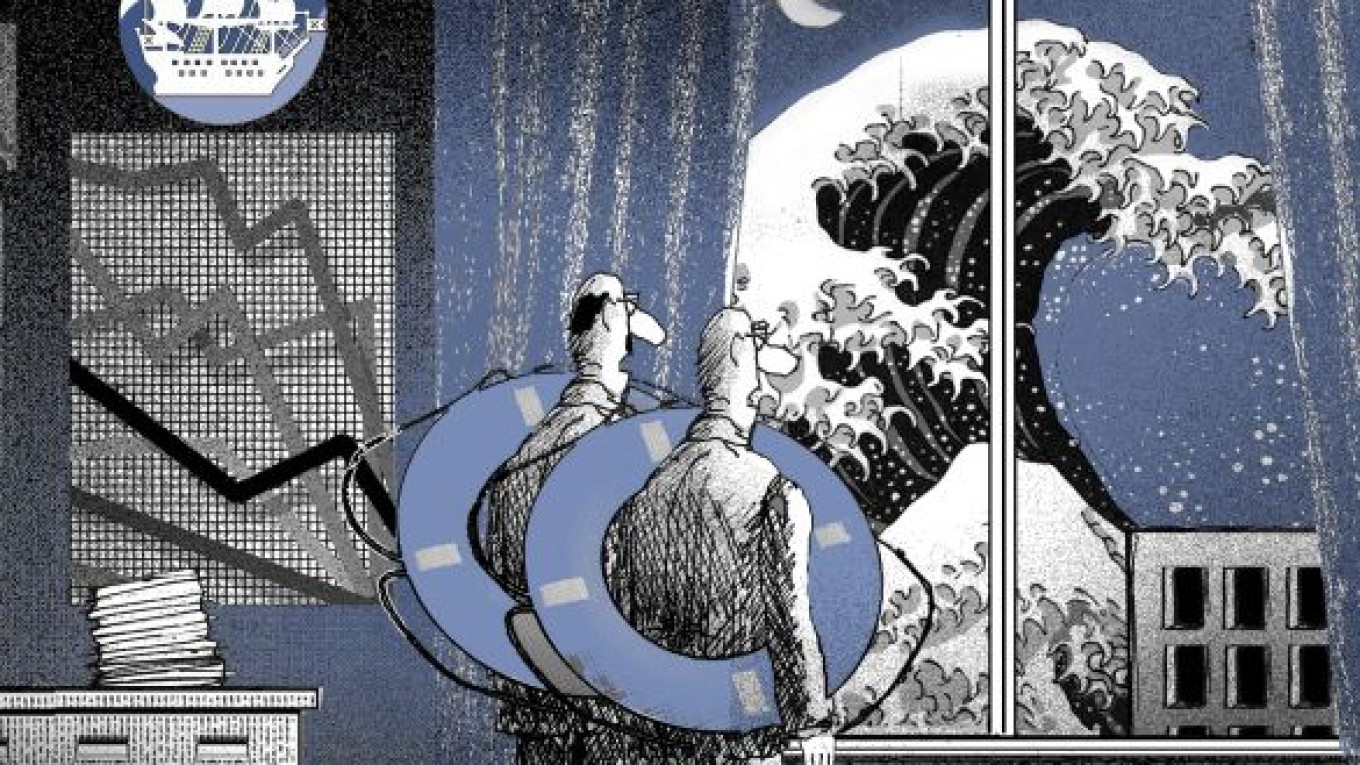

The most important issue among those is the interaction between the sovereign debt crisis in the West and the growth in the emerging markets. Will the crisis in Europe result in a financial crisis that will undermine the growth in Asia? Or will the growth and accumulated reserves of the emerging markets be sufficient to save Europe, perhaps through a bailout or a growing market for Western goods?

These questions are very hard to answer. The current situation is unprecedented. For the first time in history, it is the West that faces a major debt crisis, while the East is faring better. All the major euro-zone economies have violated the Maastricht criteria, both in terms of deficit levels and debt-to-GDP levels. While reducing deficits is feasible, it is very unlikely that the European countries will be able to decrease debt-to-GDP levels to normal levels in the foreseeable future. This means that even if the European leaders avoid a Lehman-like collapse and ensuing panic, Europe is facing at least several years, if not a decade, of slow growth. The U.S. economy is facing very similar challenges. Will the emerging markets survive the lack of growth in their main export markets?

While many discussions at the forum will focus on potential Armageddons in Greece or Spain, the global slowdown is the one issue that matters most. And it is especially important for Russia. While China and India — as well as Brazil, Chile and South Korea — did not suffer badly in 2009 when the Western economies were in a recession, the 2009 crisis hit Russia hard, through capital outflows and a dramatic fall in oil prices. It turned out that the famous “decoupling” theory, which holds that growth in emerging markets does not depend on growth in developed economies, worked only for some countries, such as China, but not for Russia.

Will this happen again? If Western politicians manage to avoid an acute crisis, the debt overhang in the United States and Europe will still result in slower growth in the global economy, even if China “decouples” again. This will inevitably lead to a decrease in commodity prices. The good news is that Russia is no longer vulnerable to the reversal of financial flows because the capital flow is already negative and both the banks and the corporate sector lack substantial foreign leverage. The bad news is that the federal budget is now much more dependent on oil prices than it was even five years ago. In 2007, an oil price of $70 or $80 per barrel would have been sufficient to attain a budget surplus, but now it would result in a substantial budget deficit.

This means that Russia will have to cut government spending or raise taxes, much like the European countries that have imposed austerity packages. Russia has low government debt, which will at least allow the country to introduce austerity measures gradually rather than overnight. But since it will have to introduce them in any event, the most important question is how exactly the government will balance its books if oil prices drop. An open discussion of these issues will help to reduce uncertainty over the future of the Russian economy. Investors would benefit substantially if a contingency plan is announced. They need to know which expenditures will be cut, which taxes will be raised and which assets will be privatized if the oil price goes down.

These choices are not obvious. Yet there are clear benefits from the stability of tax rates and early privatization. First, commitment to the current tax rates would increase confidence among investors, both domestic and foreign. Uncertainty about potential tax increases is never good for business and investment. The most straightforward way to eliminate this uncertainty is to commit to the existing rates. Second, it makes sense to privatize before oil prices — and the market value of Russian assets — falls.

While some government officials believe that Russian assets are now cheap, there is certainly no guarantee that their valuations will necessarily go up. If the global economy slows down, Russian assets may become even cheaper. In this scenario, the need for cash may force Russia to sell government assets at fire-sale prices. Therefore, the priority should not be to time the market — and governments are usually not very good at this — but to make sure the assets are sold in an open, competitive procedure. Because privatization is likely to improve corporate governance of the privatized companies as well as the overall investment climate, investors in privatized assets are likely to earn high returns. This should not be perceived as an unfair gain. In most counties, privatization results in valuation growth. At the same time, however, Russian taxpayers will benefit as well. Early privatization will both relax fiscal constraints and boost investment and productivity in the privatized companies.

Sergei Guriev is rector of the New Economic School in Moscow.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.