Lee Kuan Yew, the father of the modern Singaporean miracle, likes to say “culture is destiny.” In other words, every country lives according to its own traditions, habits and aspirations. Lee calls the Singaporean model ?€?Confucian capitalism,?€? a synthesis of the economic and technocratic attitudes and methods of the West with the spiritual values of the East.

Lee links the Singaporean miracle to the country’s Confucian culture: ?€?As long as leaders care about the welfare of the people, the people will obey them. This respect that the people held for their leaders provided a supportive attitude toward the policies of the Singaporean government. Singaporeans worked hard, saved their money and denied themselves a great deal for the sake of their children?€™s future.?€? Among other things, Confucianism inculcates hard work, discipline, modesty, humility, respect for the state and the authorities and tolerance toward other religions and viewpoints.

In contrast to Confucianism, Western democracy?€™s puts a huge emphasis on individualism and egoism — values that can only be used in small doses in Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, South Korea and other Confucian-based societies.

In a similar fashion, not all Western cultural values will work in Russia. One of the largest barriers to Russia joining the Western economic club is its ?€?bazaar market psychology.?€?

In a standard marketplace, the merchant has a permanent store and regular patrons. The dynamic is different with a bazaar, however. An unknown seller comes to the bazaar, often from some distant location, with the goal of unloading his goods to strangers ?€” in as little time and for the highest price possible. The seller might never return to that bazaar, but if he does, he is unlikely to meet the same buyers again. For this reason, he is unmotivated to worry about the quality of his goods or his reputation. What?€™s more, his income depends on how successfully he can bamboozle the buyer by, for example, mixing water with the honey or soaking the tomatoes in nitrates.

We all know the rules of buying and selling in Russia?€™s ?€?bazaar economy.?€? Today Ivanov sells Petrov counterfeit French cologne. One week later, Petrov sells Ivanov outdated medicines. After that, both Ivanov and Petrov buy rotten fish at a supermarket owned by a man who, on the same day, buys his wife a necklace of fake diamonds.

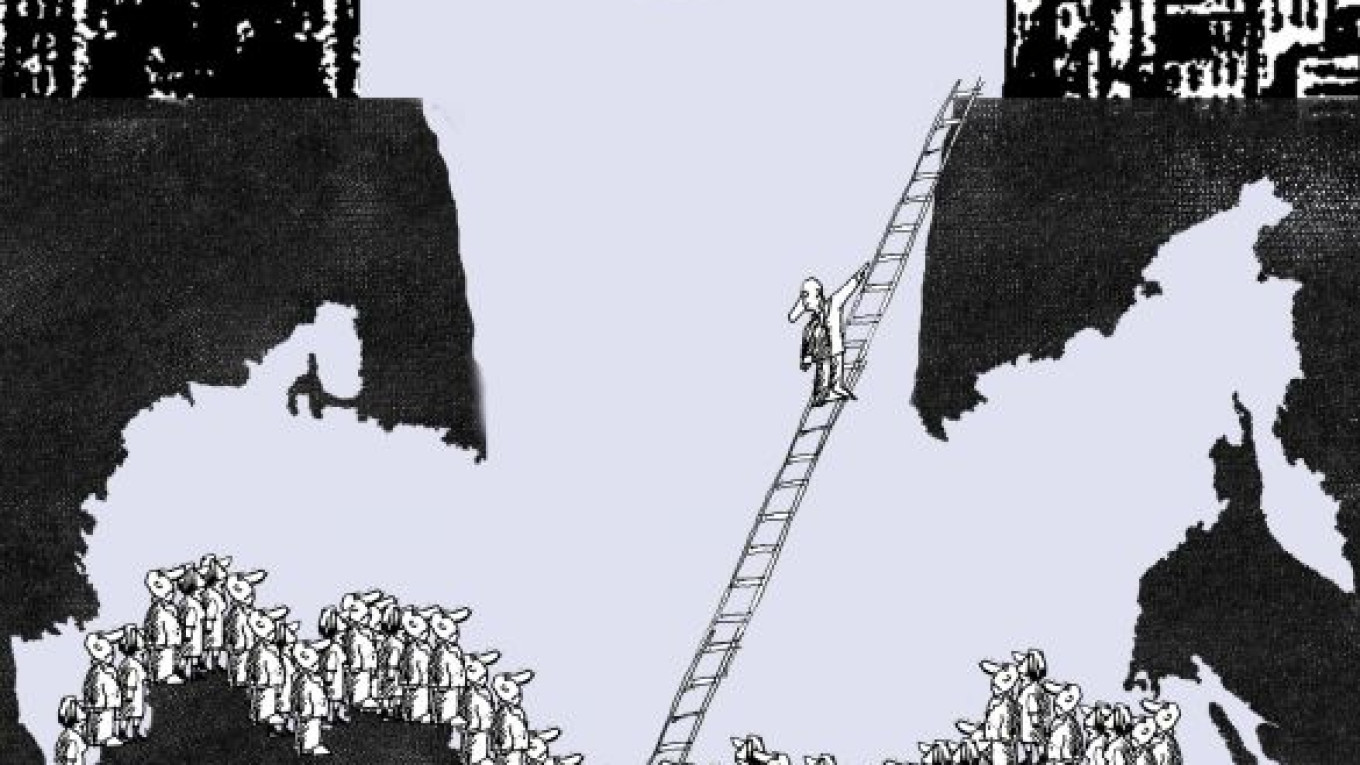

The bazaar mentality is what makes the Russian economy different from the more developed economies in the West. Another difference is that, in the West, economic development is generated from the bottom, not the top. A free-market economy is driven by people engaged in a fierce competitive struggle for maximum profit, in which only the most capable, creative and innovative come out ahead. Russia, however, attempts to drive that initiative from the top, with politicians and closely affiliated oligarchs deciding which big projects should be undertaken and at what cost, as well as where, when and by whom they will be implemented. And the more the cost is inflated and the less effective it is in practice, the more profitable the project is for the people at the top. That is why Russia and the West cannot compete as equals.

It is well known that Russia suffers from a chronic inferiority complex in relation to the West. As a result, the Kremlin is fixated on achieving parity with its competitors in those few, narrow sectors where it is still possible, such as nuclear weapons (and even here nuclear parity is a big stretch given the numerical and quality gap between the two countries).

Obsessed with securing its place in the international arena as a leading global power, Russia doesn?€™t see the forest for the trees. It spends woefully little on science, education, health care and the environment, while spending billions of dollars on big-ticket prestige items, such as space missions, the Olympics and international pop music contests.

Russia is not only failing to catch up with the West, it is lagging farther and farther behind it with each passing year. The harsh reality is that the world doesn?€™t respect a laggard ?€” especially if that laggard wastes most of its resources on throwing a spaceship into orbit or a huge, extravagant Olympic party for the world to attend.

If Russia wants to become a leading, post-industrial country of the 21st century, it will have to improve its culture. Lee was exactly right when he said a nation?€™s culture truly determines its destiny.

Yevgeny Bazhanov is vice chancellor of research and international relations at the Foreign Ministry?€™s Diplomatic Academy in Moscow.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.