Jens Stoltenberg, who replaced Anders Fogh Rasmussen as NATO secretary-general on Oct. 1, is no novice when it comes to dealing with Russia.

When he was prime minister of Norway, Stoltenberg forged a border agreement with Russia's then-President Dmitry Medvedev. After 40 years of negotiations, Norway and Russia finally reached an agreement over the demarcation lines of their Arctic borders in September 2010.

In retrospect, the border deal was hugely important to Norway. It ended a dispute that for four decades had rankled Norway's relations with Russia. With that border dispute now over, Norway's foreign policy is free of any constraints.

As NATO's new chief and someone who knows Russia and NATO very well, Stoltenberg has no illusions about the Kremlin or NATO's shortcomings. With the Ukraine crisis far from resolved, there is no reason to believe he is going to hurry to repair ties between the alliance and Russia. It is even difficult to see under what circumstances Stoltenberg could begin to do that.

Ever since Russia annexed Crimea in March and provided military support and intelligence to the pro-Russian rebels in eastern Ukraine, Norway — along with fellow NATO members Denmark, Poland and the Baltic states — has been very outspoken about Russian involvement in Ukraine. The same could be said of other Nordic countries, including Finland and Sweden, which are not members of NATO.

Common to all these countries is a shared perception of threats. For them, that threat is Russia. As a result, the Ukraine crisis has changed the foreign, security and defense postures of this part of Europe. Sweden and Finland now want to cooperate with NATO. There is even a lively debate taking place in Stockholm and Helsinki about whether they should in fact join NATO.

The Ukraine crisis has also spurred closer defense and security cooperation between Norway and Sweden, Finland and Denmark, and Poland and the Baltic states.

In short, Russian President Vladimir Putin's policies in Ukraine have created a special kind of understanding among Nordic countries. Any illusions they harbored about Russia are gone. By annexing Crimea and conducting a hybrid war in eastern Ukraine, Russia broke the rules of the post-Cold War consensus.

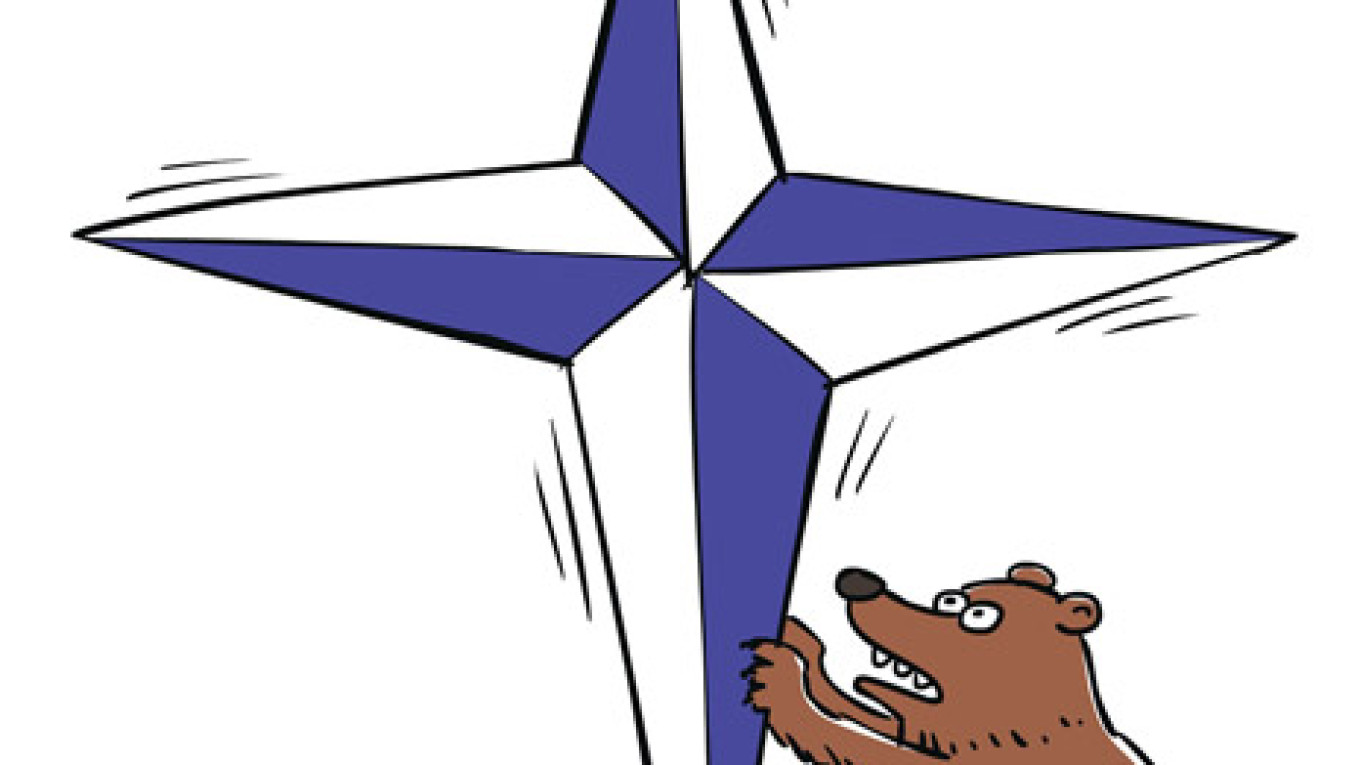

What this means for NATO is that the Ukraine crisis has ended the post-Cold War era. NATO has entered a new chapter in its relations with Russia.

This is not a bad thing.

For far too long, there was the hope that NATO and Russia could establish a modus vivendi once former Eastern Bloc states began joining NATO.

When Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic joined NATO in 1999, the alliance tried to sweeten the pill for Moscow by setting up the NATO-Russia Council, or NRC. For Russia, the NRC was a mere talking shop, which is precisely what some NATO countries wanted, while others wanted the NRC to have more substance. In any event, the NRC was a half-hearted attempt to establish some cooperation and dialogue with Russia.

Stoltenberg's predecessor Rasmussen tried to engage Russia's military through, for example, establishing search-and-rescue exercises between NATO and Russia as well as consultations with the Russian military. The goal was to build some kind of trust in the hope of weakening Moscow's suspicion of NATO. Russia's annexation of Crimea put paid to that cooperation.

Not only that, Rasmussen pulled no punches when he lambasted Russia's support for the pro-Russian rebels in eastern Ukraine. He also released satellite pictures showing movements of Russian troops along the border with Ukraine so that no NATO country had any doubt about Russia's support for the rebels.

Yet for all his criticism of Russia, Rasmussen and NATO drew their own red lines. At the NATO summit in Wales in September, leaders did not offer Georgia or Moldova the Membership Action Plan that would have set them on the path to join NATO.

Instead, they promised them much closer cooperation. With Russia in mind, clearly, NATO was not ready to go to war against Russia on behalf of Georgia by invoking Article 5 that obliges members to defend other members in case of an attack.

Nor did NATO agree to deploy troops among its Eastern European member states on a permanent basis, something that Germany had opposed. Instead, it agreed to boost the defenses of the Baltic states and Romania. Indeed, Stoltenberg's first visit as secretary-general was to Poland. Inevitably, he was asked about how he would deal with NATO's future relations with Russia — and Ukraine.

He didn't mince his words. The crisis in Ukraine, he said, was "caused by Russia's military intervention, which is a major challenge to Euro-Atlantic security." He also said NATO would continue its full support for an independent, sovereign and stable Ukraine.

And while Stoltenberg also insisted that each European nation "must be free to decide its own course," it is hard to see NATO admitting Georgia in the near future, not to mention Ukraine's long-term strategic and security goals.

As for NATO's relations with Russia, Stoltenberg spelled out the conditions for NATO resuming any kind of cooperation — assuming that Russia wants it.

"We need to see a clear change in Russia's actions. A change that demonstrates compliance with international law and with Russia's international obligations and responsibilities," Stoltenberg told reporters in Brussels on Oct. 1, his first day at his new job.

"Let me be clear," he added. "I see no contradiction between a strong NATO and our continued effort to build a constructive relationship with Russia. Just the opposite. Only a strong NATO can build such a relationship for the benefit of Euro-Atlantic security."

For now, NATO is not strong. Most of its 28 members are not prepared to spend more on defense, particularly since Europe's economies remain weak. Yet even sluggish economic growth has not persuaded NATO countries to pool and share resources that would create more efficiency, reduce costs, lead to more interoperability and create a more cohesive alliance.

For all these shortcomings, NATO will have to deal with a Russia that will test its willingness to protect even its members. Indeed, the kidnapping last month of an Estonian intelligence agent and the detention of a Lithuanian fishing vessel by Russian border guards are Russia's way of testing NATO.

Those cases also show just how difficult it will be for Stoltenberg to put relations between NATO and Russia on a new footing — if Russia wants to open a new chapter.

Judy Dempsey is senior associate and editor-in-chief of Strategic Europe at Carnegie Europe.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.