President-elect Vladimir Putin is returning to the Kremlin as a diminished figure. With nearly 64 percent of the vote in the March 4 election, he can still lay claim to significant residual support in Russian society. Yet his system of personalized power has entered a period of existential crisis as the previously quiescent middle class in Moscow and other major cities has signaled that its interests are no longer served by the current "managed democracy."

Putin has lost his Teflon coating amid unprecedented criticism of his rule from within Russia. His triumphant election victory is a sign of systemic weakness rather than strength. Putin was forced to come back because the system depends so heavily on him as an individual. The outgoing president, Dmitry Medvedev, clearly never inspired sufficient confidence among the regime's high-level stakeholders to become a real president and was perhaps never intended do so.

What is now likely to happen? Putin knows that he has to contain frustration among the middle class. Measures designed to let off steam are being enacted, including bills in parliament to lower the threshold for political parties to participate in elections and to return to a system of elected governors. Medvedev has even ordered a review of former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky's 2010 criminal conviction for embezzlement. These initiatives would clearly not have occurred without the efforts of tens of thousands of Russian citizens who took to the streets in December and February to assert their right to have their votes counted fairly.

In the economy, Putin is likely to announce new reformist policies to show that Russia's tired-looking leadership has not run out of ideas. The highly competent economist Alexei Kudrin could return to the government if, for example, Putin decides not to name Medvedev as prime minister. This would be welcomed by many businesspeople in Russia and the West.

These reformist policies and the likely co-opting of some of the liberal opposition may buy time, but they will not be enough to stem the sense of disillusionment and alienation among the most dynamic and active segments of society.

In theory, Putin now has an excellent opportunity to respond to pressure from this so-called creative class and finally resolve the issue of property rights. He could also allow a post-Soviet generation to develop political parties that will galvanize the creative energies of society and develop political institutions as a basis for genuine modernization. This would undoubtedly be an impressive legacy and establish him as one of Russia's greatest leaders.

Putin, a keen student of Russian history, has invoked the image of Alexander II who initiated successful reforms after Russia's defeat in the Crimean War in 1855. But Putin's reformist rhetoric needs to be backed up by action. Over the past eight years, his system has consistently demonstrated unwillingness to contemplate real political reform and, as a result, has pursued only token measures to develop the economy.

Russia's current rulers have a vested interest in maintaining a noncompetitive political and economic environment because they and their bureaucracy are the direct beneficiaries. To hold onto power and wealth, they require managed elections, a compliant judiciary and loyal law enforcement agencies. This system can only be dismantled and transformed if the elite understand that there is no other alternative. No less important, they would need assurances of a safe exit to make a calm, peaceful transformation possible. The ruling elite are already starting to realize that preserving the system has become much harder. This may be the beginning of a gradual transformation of the status quo.

While street protests are already fizzling out, this is by no means the end of pressure for change from below. Since December, new opposition forces have emerged. Competitive elections in the regions for mayors and governors are going to give these new political players an important opportunity to coalesce and achieve results.

Ultimately, it is the economy that will determine the speed of change. With high oil prices, low levels of public debt and 4 percent economic growth, Russia is unlikely to face short-term difficulties. Yet the longer-term problems are mounting up quickly and may be beyond the regime's ability to manage them. These problems include a shrinking labor force, low levels of capital investment and the urgent need to raise labor productivity and reduce exposure to the oil price. A prolonged euro-zone recession could easily push down the oil price and shake the system to its core.

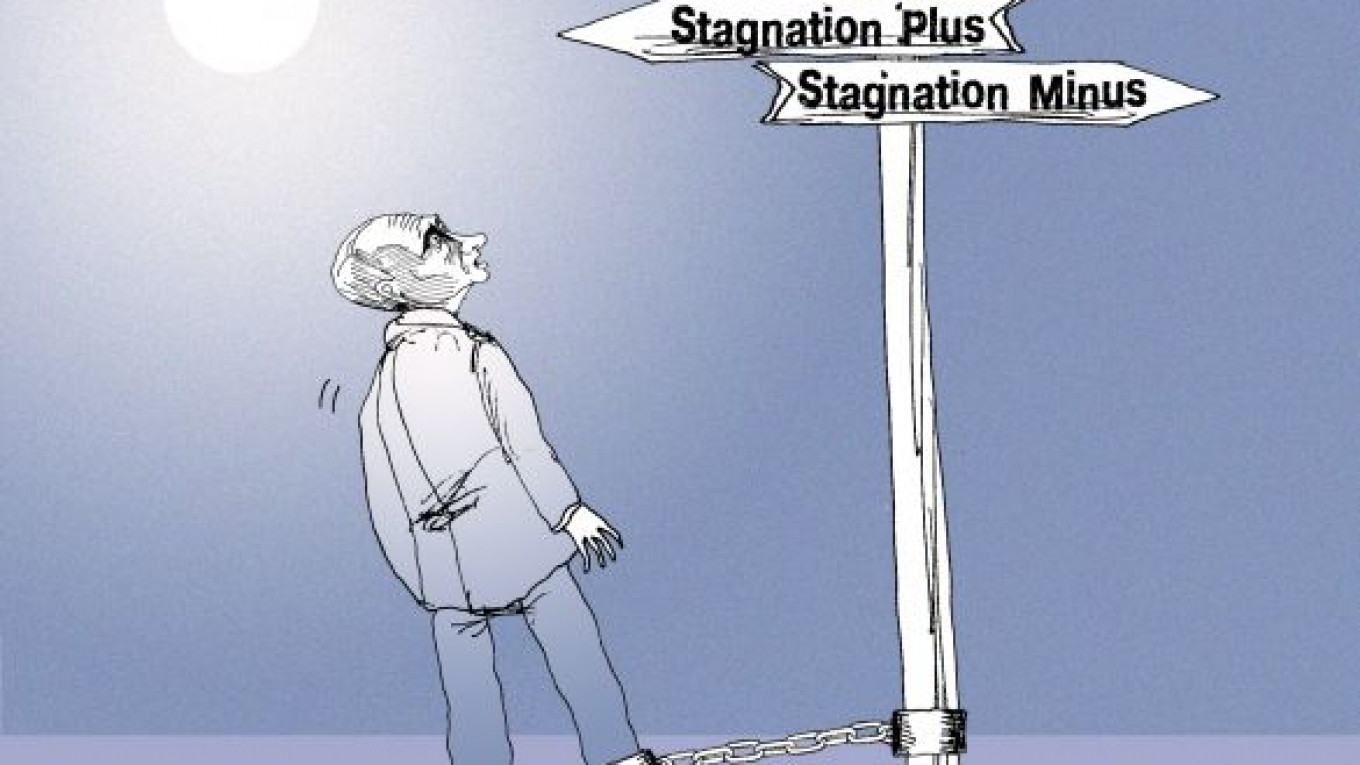

For the foreseeable future, Russia is likely to steer between two paths — "stagnation plus" and "stagnation minus" — with neither resulting in a decisive breakdown or a qualitative breakthrough. Any way you look at it, this outcome is far from being a recipe for stability and will only erode Putin's model further.

John Lough is an associate fellow of the Russia & Eurasia Programme at Chatham House and vice president BGR Gabara, a public affairs and strategic consulting company.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.