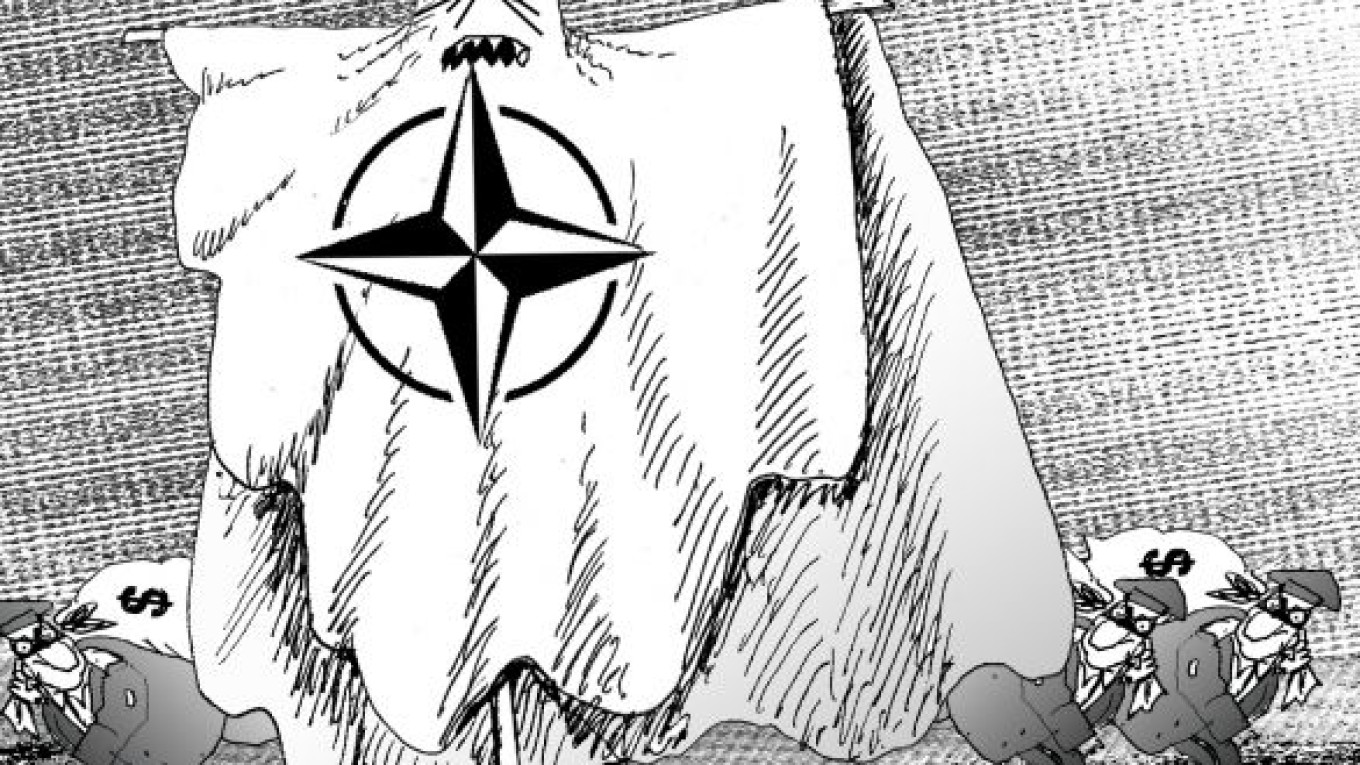

Once again, we have learned that NATO is the greatest external security danger to Russia. But this time it’s not coming from the country’s arch-conservative journalists or analysts carping at the alliance’s evil intentions on government-controlled television but from the holy of holies in terms of Russia’s national security documents — the new military doctrine that President Dmitry Medvedev signed on Feb. 5 — conveniently timed to steal the show during the Munich security conference the same day. Unfortunately, the doctrine marks a new, aggravated phase in Russia’s NATO-phobia.

In Article 8 of the doctrine, NATO got the No. 1 spot among Russia’s 11 most important external military dangers. Global terrorism is way down the list at No. 10.

Medvedev noted rather disingenuously in an interview published Thursday that NATO is not a “threat.” What he was referring to was that the doctrine had two separate categories: Russia’s greatest “threats” and its “dangers.” NATO was No. 1 in the danger category only.

Whether it is called a threat or a danger, it is bad for U.S.-Russian relations any way you look at it. Things were looking so good after U.S. President Barack Obama took office a year ago. First, he supported the campaign to shelve NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia, the two sorest spots in NATO-Russian relations. What’s more, Viktor Yanukovych’s presidential victory now means that NATO membership for Ukraine is a nonissue.

As for Georgia, this was always considered a neocon project of former President George W. Bush, and Obama has been all too eager to distance himself as much as possible from this foreign policy disaster, particularly after Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili recklessly sent tanks into South Ossetia in August 2008. More important, NATO, according to its own rules, cannot accept new members that have unresolved internal territorial disputes. Since NATO doesn’t recognize the independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, alliance membership for Georgia is all but impossible as long as Russia has troops and bases there.

Since Georgia and Ukraine are off the NATO agenda, it is not clear what the doctrine meant when it warned of the danger of NATO’s infrastructure “approaching Russia’s borders.” Who exactly are the ferocious NATO enemies at Russia’s gates? The Baltic states? These three tiny countries have a total of 25,000 active military personnel and 25 shoulder-launched surface-to-air missiles, while their combined air force consists of about a dozen aging Czechoslovakian and Soviet trainers, military transporters and utility helicopters. Not exactly the stuff to make Russia’s generals stay up at night worrying about an attack.

Perhaps the doctrine was referring to NATO’s Baltic Air Policing force — four NATO-member aircraft that patrol the Baltic states’ airspace — but this hardly constitutes “infrastructure.” The NATO threat to Russia is clearly political, not military.

The main reason the Baltic states sought NATO membership is to fall under NATO’s collective security guarantee — Article 5 of the NATO Charter, which says any attack on any member shall be considered an attack on all. But since Russia has no plans to attack the Baltics, the Article 5 collective-defense provision should not concern Moscow.

This NATO-phobia looks particularly strange when one of NATO’s key members — France — set a new precedent and agreed to sell a Mistral assault ship to Russia. These 23,700-ton, 210-meter long helicopter and command ships will probably be deployed in the Arctic and in the Black Sea. (If Russia had just one of these ships during the 2008 war with Georgia, it could have subdued Georgia in just 40 minutes, according to Navy command chief Vladimir Vysotsky.) With “enemies” like France selling supermodern assault ships, Russian doesn’t need friends like Venezuela, Iran or Cuba.

Whatever happened to the famous clause enshrined in the Founding Act on Mutual Relations signed by NATO and Russia in 1997 — that “NATO and Russia do not consider each other as adversaries”? It has now been definitively replaced by Military Doctrine 2010, which marks the apogee of the Kremlin’s 10-year propaganda campaign to turn a nonadversary into an adversary.

How can we get back to the cooperative spirit of the Founding Act? Yury Shevchuk, the legendary singer of the rock group DDT who is famous for his liberal political views, joked in a 2008 interview on Ekho Moskvy radio: “What is so terrible about NATO? Russia should join the alliance. Maybe as a member we could even undermine NATO from within with our alcoholism, laziness and pofigizm [a couldn’t-care-less attitude]. That is the best way to solve Russia’s NATO problem!”

There are two possible explanations for Russia’s NATO obsession. The first, which is commonly quoted in the West (but incorrect), is that Russian leaders suffer from chronic clinical paranoia. The other (correct) explanation is that they are as healthy as horses but feign the paranoia for internal political purposes and to justify huge defense expenditures to defend against a NATO invasion — which, of course, is only a cover for bureaucrats to plunder the funds. This is a vivid example of how NATO-phobia helps fuel corruption.

The military significance of Article 8 is minimal since few in the West believe this nonsense any more than Russia’s leaders, but the political significance should not be underestimated. This is only the third doctrine in Russia’s post-Soviet history and the first time that NATO was specifically named as a danger and given top billing.

Why all the hysteria over NATO when everyone — including Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, hardline generals and pro-Kremlin archconservative analysts — knows that it is rubbish? One reason has to do with Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov’s military reforms. Feb. 15 marked his three-year anniversary as head of the Defense Ministry, and in this short period he has already carried out real, painful reforms despite fierce opposition from the officer corps and generals. About 180,000 officers have already been fired, and Serdyukov has shut down a few of the corruption schemes that have fattened the military at all levels for years.

But Serdyukov has to be careful that he doesn’t step on too many toes too quickly. On one hand, he must show Putin and Medvedev that he is cutting the tremendous fat and modernizing the army, but he doesn’t want to spark a rebellion among the top brass. NATO may have been included in the doctrine to throw a bone to Serdyukov’s opponents, The key to this strategy is to delay the reforms as much as possible for the hundreds of thousands of military personnel who could easily fall under the category of “fat” — at least until they reach retirement age. Crying “NATO!” is a tried-and-true obstruction method and is particularly effective since it jibes so well with the Kremlin’s protracted propaganda campaign that “enemies are at the gate.”

In the Feb. 22 issue of Vlast, Russia’s envoy to NATO, Dmitry Rogozin, was asked, “What is Russia’s greatest threat?” He answered: “Our biggest enemies are [our own] weakness and lack of confidence and corruption, which erodes the state … Of course, enemies can always be found, but the weaker the country, the more enemies there are.”

He hit the nail on the head. Sometimes, Rogozin can’t help but tell the truth, and kudos to him for this. To deal with the real threats that Rogozin mentioned, Medvedev should immediately amend Article 8 of the new military doctrine. He needs to remove the entire first point about NATO and replace it with corruption as the No. 1 threat to the territorial integrity and survival of Russia.

Medvedev and Putin should mobilize all of the country’s resources — both military and civilian — to fight against this dangerous and insidious enemy and forget once and for all about fighting imaginary ones.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.