There is, of course, the fiction by Vladimir Nabokov — “The Gift,” “Lolita” and “Ada.” His novels were biographical and nonbiographical at the same time. He never wrote about politics, yet he did. Then there is his own fiction of his own writing and his own past — “Speak, Memory” and “Strong Opinions.”

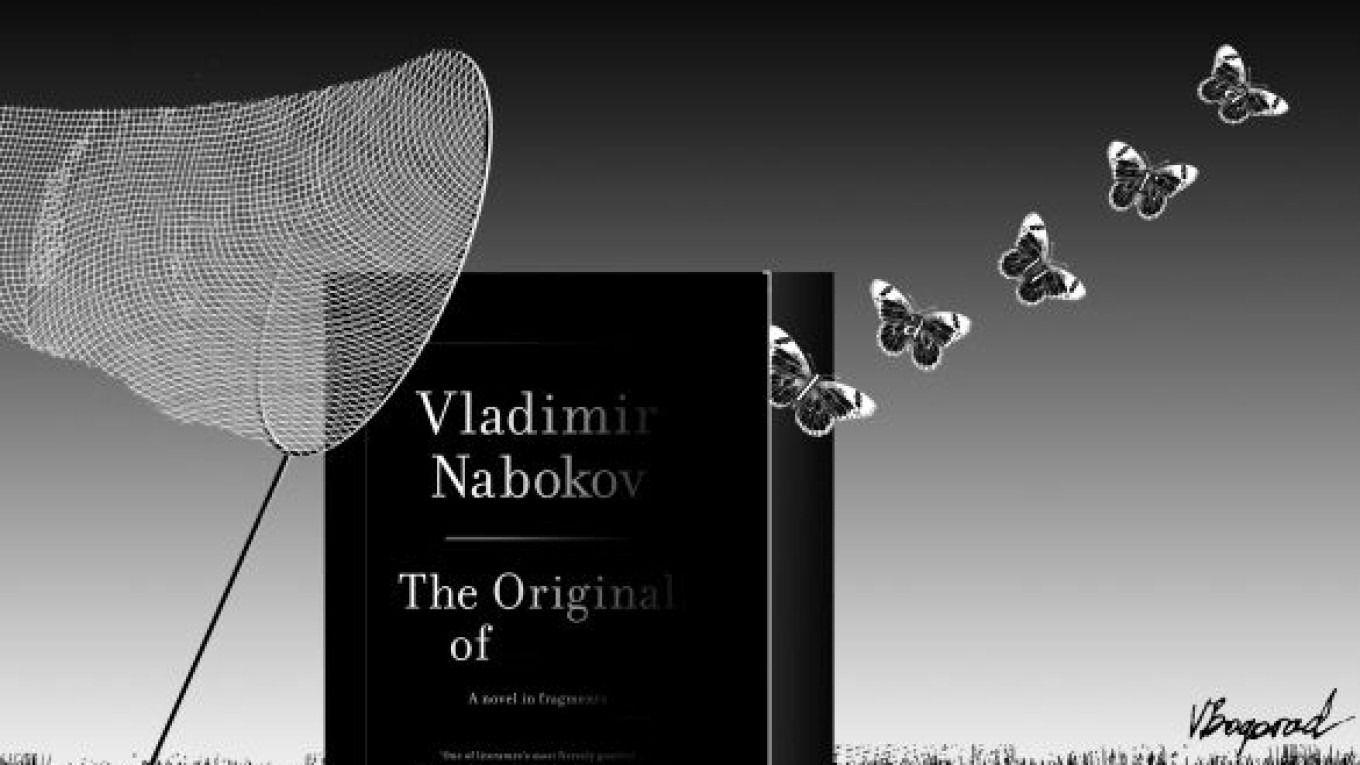

And now there is “The Original of Laura: A Novel in Fragments,” which has encompassed all these fictions. Nabokov’s most final and yet most unadorned work — 275 pages of the writer’s signature plain index cards written from 1975 to 1977, the last years of his life. It is a carcass of the books that he already wrote, a conclusion to all those books, a poetic medley.

First, the volume itself is fiction — the most beautiful book that I have ever seen — designed by U.S. author and graphic designer Chip Kidd: a simple black cover, bold white letters vanishing gradually. It is an exit, a preface, a conclusion and an entrance into what we have already read.

Then there is the history of the publication — also a piece of fiction. Nabokov, who by his own admission has “rewritten — often several times — every word I have ever published,” resolutely guarded his authorial image. He endlessly wrote forewords and afterwords to his novels, and he naturally wouldn’t want any book to be published unfinished, imperfect, without having the last word.

Nabokov passed away in 1977. Knowing the end was near, he ordered Vera, his trusted wife, to burn the unfinished manuscript. Vera, who twice saved “Lolita” from incineration, didn’t fulfill Nabokov’s wishes, and the difficult job fell on their son, Dmitri. The story goes that after years of hesitation Dmitri finally made a decision to publish “Laura,” purportedly after his father’s ghost appeared before him requesting the publication.

Some cynics claim that the Nabokov estate assisted in creating the fiction around Nabokov’s fiction — to burn or not to burn. In this way, a controversial — and thus profitable — publication was a sure thing.

But we should never believe that the work of art exists purely because of physical, commercial reasons. Indeed, when Nabokov gave up his native Russian for writing in English, this move was explained by his geographical relocation to the United States from war-torn Europe. He, it is said, had to write in English to get published and to ease up his familial responsibilities. Maybe this is true, but how many other immigrant writers faced with the same choice have remained national authors (even without a nation), not international luminaries.

In short, no event in a writer’s life is random. Certainly not in Nabokov’s case. In fact, he moved from Russian into English not because he needed to earn a living in a foreign land but because at the time he had nothing to say to his native one. Furthermore, such different writers as Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Isaac Babel both insisted, “Nabokov is lost to Russian literature.” Instead, Nabokov was gained by American literature. Imagine the world today without “Pnin” or “Pale Fire.”

Now we are fortunate to have “Laura.” In his introduction, Nabokov’s son, Dmitri, wrote that his father wouldn’t have been against his decision to publish “Laura.” Dmitri wrote that he “could no longer even think of burning ‘Laura,’ and [his] urge was to let it peek for an occasional instant from its gloom.” Thank you, Dmitri Vladimirovich!

“Laura” is the origins of Nabokov’s fiction — drafts, scales, drawings. Alexander Pushkin, Ludwig van Beethoven and Peter Paul Rubens also labored over a completion of their final masterpieces. We have the published “Pushkin’s Unpublished Diaries” and exhibits of Ruben’s sketches. “Laura” is the start and the successor of “Lolita” — that same theme of nymphomania, Humbert H. Humbert (now “pathetic and harmless”) and Flora, Laura, (Lolita?) all grown up. There is a wallpaper pattern right out of “Pnin,” a feverish childhood dream of a monster, which in “Laura” is bravely erased: “Finally it gave up — as some day life will give up — bothering me,” the origins and the deletion, all at once.

You may recall the illustrious chronophobiac’s account at the beginning of “Speak, Memory” who experienced something like panic when he looked for the first time at homemade movies that had been taken a few weeks before his birth. But what particularly frightened him was the sight of a brand-new baby carriage standing there on the porch, with the smug, encroaching air of a coffin. Even that was empty, as if, in the reverse course of events, his very bones had disintegrated.

Nabokov, preserved for posterity by his books, was certain that life wouldn’t go on without him after his death — but before birth. Only the fact of his nativity guarantees his posthumous existence.

This empty pram, now also a coffin, “Laura,” is filled with the Nabokov genius, the draft written after the fact, the beginning and the end to his fiction, an outline and a conclusion to his life: “Dying is fun.” The first and last index card affirms, “Efface, expunge, delete, rub off, wipe out, obliterate.”

We collect artists’ scrapbooks and poets’ sketches. Nabokov’s own notebooks are guarded by the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library. We are grateful that Nikolai Gogol’s second volume of “Dead Souls” — at times filled with didactical treatises, spiritual and religious preaching — survived the author’s distraction as evidence to his (imperfect) genius.

As every reader of Mikhail Bulgakov can confirm, “Manuscripts don’t burn.”

Nina L. Khrushcheva teaches international affairs at The New School in New York. She is the author of “Imagining Nabokov: Russia Between Art and Politics.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.