Russia’s new military doctrine offers a tried-and-true bogeyman — missile defense, which is listed as the country’s fourth-greatest external military danger. According to the doctrine, strategic missile defense will “undermine global stability and destroy the balance of power in the nuclear missile sphere.”

Whatever happened to the bold statements made between 2004 and 2007 by then-President Vladimir Putin, then-Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov and leading generals that Russia’s new generation of intercontinental ballistic missiles were “capable of penetrating any existing or future missile defense systems”? With such confidence in its offensive capabilities, it is odd that Russia has ranked missile defense as its No. 4 Danger.

Apart from this silver bullet, many people thought the Kremlin’s concern over missile defense was put to rest when U.S. President Barack Obama in September canceled plans to deploy elements of a missile defense shield in Poland and the Czech Republic. Now, however, Deputy Prime Minister Ivanov says Obama’s alternative — SM-3 interceptors to be deployed in the Black Sea territorial waters of Romania and possibly Bulgaria in 2015 — is “just as bad or even worse.” This criticism is bizarre considering that a year ago the Kremlin itself suggested these countries as an alternative to Central Europe.

How could these SM-3s possibly pose a danger to Russia’s security? With a range of only 500 kilometers — with plans to upgrade them to a maximum 1,000 kilometers by 2020 to reach Iranian midrange missiles in flight — the few dozen SM-3s planned for Romania or Bulgaria clearly cannot reach Russia’s ground-based nuclear weapons that are located thousands of kilometers away.

But Russia need not worry in any case. It takes roughly 10 interceptors to shoot down a single advanced missile — and this is only in the best of circumstances. To come even close to weakening Russia’s nuclear missile capabilities, the United States would have to place thousands of interceptors along the direct flight trajectory between Russia and the United States — perhaps in Greenland — and add thousands more interceptors to its installations in Alaska and California, which now number about 40 interceptors in total. Regardless of who is president, the U.S. House of Representatives would never approve the hundreds of billions of dollars needed to build such a massive missile defense system for the simple reason that the United States doesn’t view Russia as an enemy. The Cold War is long over.

What the United States is truly concerned about, however, is a single missile attack from a rogue country. This is why U.S. long-term strategic defense plans call for a global network of limited missile defense installations. But even at the height of this project, the number of interceptors would be too small and the locations would be too far removed from a Russia-U.S. missile trajectory to in any way weaken Russia’s strategic nuclear forces, undermine the country’s nuclear deterrence or destroy the nuclear balance of power.

If Danger No. 4 of the military doctrine is referring to a mythical U.S. “global nuclear shield” that would give the United States the ability to launch a nuclear first strike against Russia while being 100 percent protected against a retaliatory strike, this would be even more absurd. The Kremlin should remember U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s “Star Wars” program in the 1980s. It turned out to be the bluff of the century, and it is just as much science fiction today as it was then.

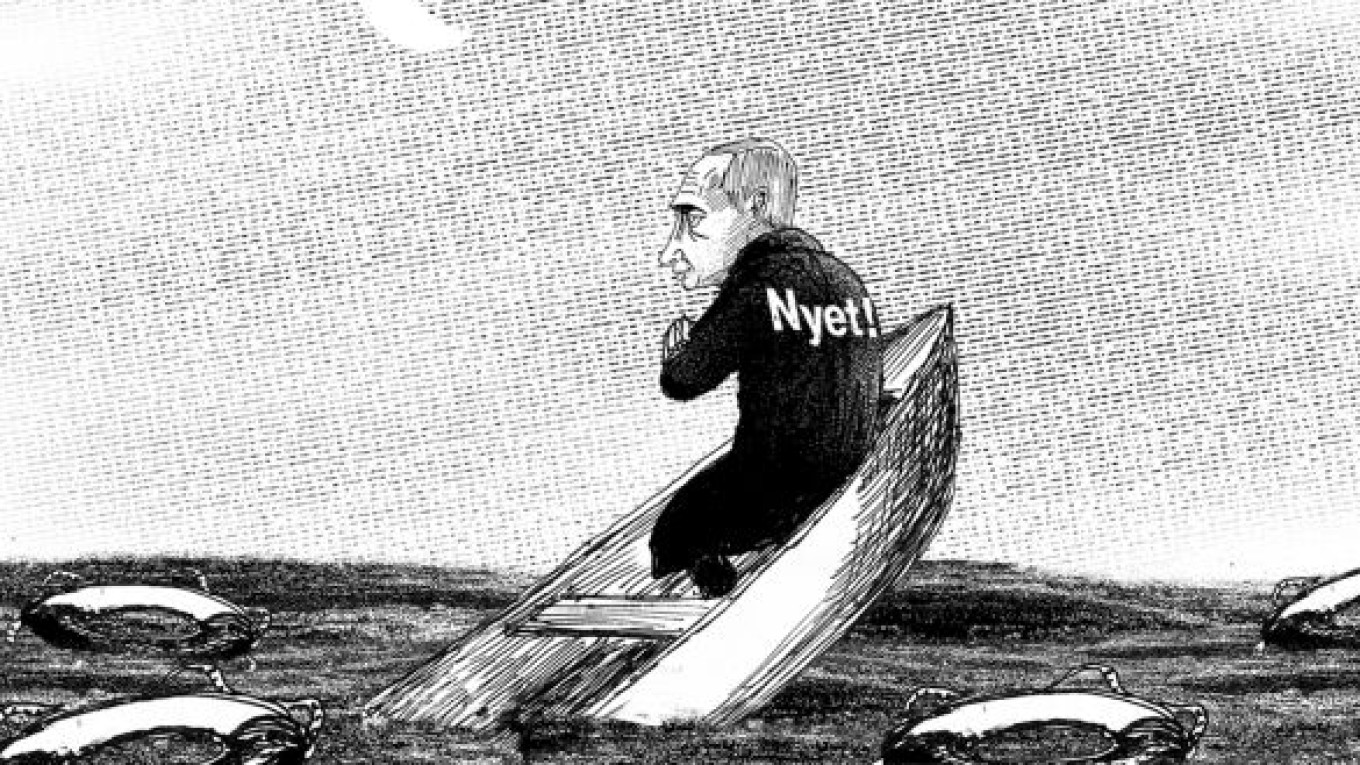

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union had parity with the United States as a superpower and was able to project its power all over the world. Now Moscow has trouble projecting its power even in the Commonwealth of Independent States. But one way it can still project its strength globally — and particularly vis-a-vis the United States — is to be the spoiler in international affairs, a modern-day version of “Mr. Nyet.”

Missile defense has become a great excuse for Russia to say “Nyet!” at every opportunity. The paradox is that while Russia disingenuously claims that U.S. missile defense undermines its security, it is precisely the absence of a nationwide missile defense system in Russia that undermines its security. The country is particularly vulnerable in the North Caucasus and Southern Federal districts and along its long border with China.

NATO and the United States have offered many times to build a limited joint missile defense with Moscow to protect against individual rogue nations that are located much closer to Russia and pose a threat to Russia no less than they do to the United States. The latest proposal for joint missile defense was put forward by U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on Feb. 23. But the Kremlin has no other choice but to say “Nyet” to these offers because it has driven itself into a corner. In cannot cooperate with the United States or NATO on missile defense when its firm, official position is that it will be used against Russia.

Although the Kremlin’s stubborn position could simply be a banal negotiation tactic to gain key U.S. concessions, it could also be meant to spoil — or, at the very least, stall — a follow-up treaty to START, which expired Dec. 5. For the past three months, senior U.S. and Russian officials have been making optimistic statements that a final deal is just weeks away, but each time last-minute snags prevent the agreement from being signed.

The Kremlin’s position could also be intended to snarl Obama’s larger global nuclear disarmament agenda — including the Global Nuclear Security Summit in April, which Obama will host in Washington, and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference in May in New York. The Kremlin’s goal is clearly not to derail the two conferences since they are too important for global security but to simply make life difficult for Obama, who badly needs the START follow-up signed by both sides as soon as possible and well before the two conferences begin.

Impeding the START follow-up is also a paradox because reducing nuclear weapons is just as advantageous to Russia as it is to the United States. As long as there is nuclear parity between the two countries, any nuclear warheads exceeding roughly 1,000 are an unnecessary economic burden for both countries — especially for Russia — and don’t add any additional value in terms of deterrence. Nonetheless, when asked by a reporter Dec. 29 in Vladivostok what the biggest problem was in the negotiations, Putin said, “The problem is that our American partners are building an anti-missile shield and we are not.”

Missile defense is like Russia’s “Fairy Tale About the Little White Bull,” in which the same phrase is stubbornly repeated over and over again. In the real world, it is: “U.S. missile defense threatens Russian national security” — regardless of where it is deployed and its limited capacity.

As the antipode of former U.S. President George W. Bush, Obama has taken a diametrically opposite approach to Russia, and his “reset” program offers a real chance to improve U.S.-Russian relations. But it takes two to reset.

The Kremlin’s spoiler role on missile defense and other issues shows that it is determined to foil the reset. Russia’s liberal opposition leaders love to compare Russia to a restless teenager whose petty “hooliganism” in global politics is meant to remind the United States that it still exists as an international player and that key global issues cannot be resolved without Russia’s participation and consent.

Although the analogy could be dismissed as typical bile from the opposition, there is a positive side: In December, the Russian Federation turned 18, which means that in only two years Russia won’t be a “teenager” anymore in any case. This could be exactly what is needed to reset relations.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.