It was a close call. After a bitter election campaign that pitted pro-European parties against a well-financed pro-Russian Party of Socialists, Moldovans opted for a European course in parliamentary elections on Nov. 30. The results showed a country torn between moving closer to Europe or to Russia.

The Liberal Democrats, the Democratic Party and the Liberal Party together won 45.5 percent, or 54 seats, of the parliament. Assuming they can end their reputation for squabbling and corruption that was often the hallmark of their stint in government over the past five years, they will form Moldova's next coalition.

It will not be an easy ride for them. The radical-left Party of Socialists, led by Igor Dodon and staunchly supported by President Vladimir Putin, won 21 percent of the vote, thus becoming the country's biggest political party.

Russia's ambassador to Moldova, Farit Mukhametshin, didn't hide his delight about the party's meteoric rise. He visited the socialists' headquarters on Dec. 2 and lavished congratulations and praise on their leadership. Along with the homegrown communists, who won 18 percent of the votes, the leftist and anti-European parties will now have 44 seats in the 101-member parliament.

No wonder then that the outcome of the election will test the commitment of the European Union to this small and poor country.

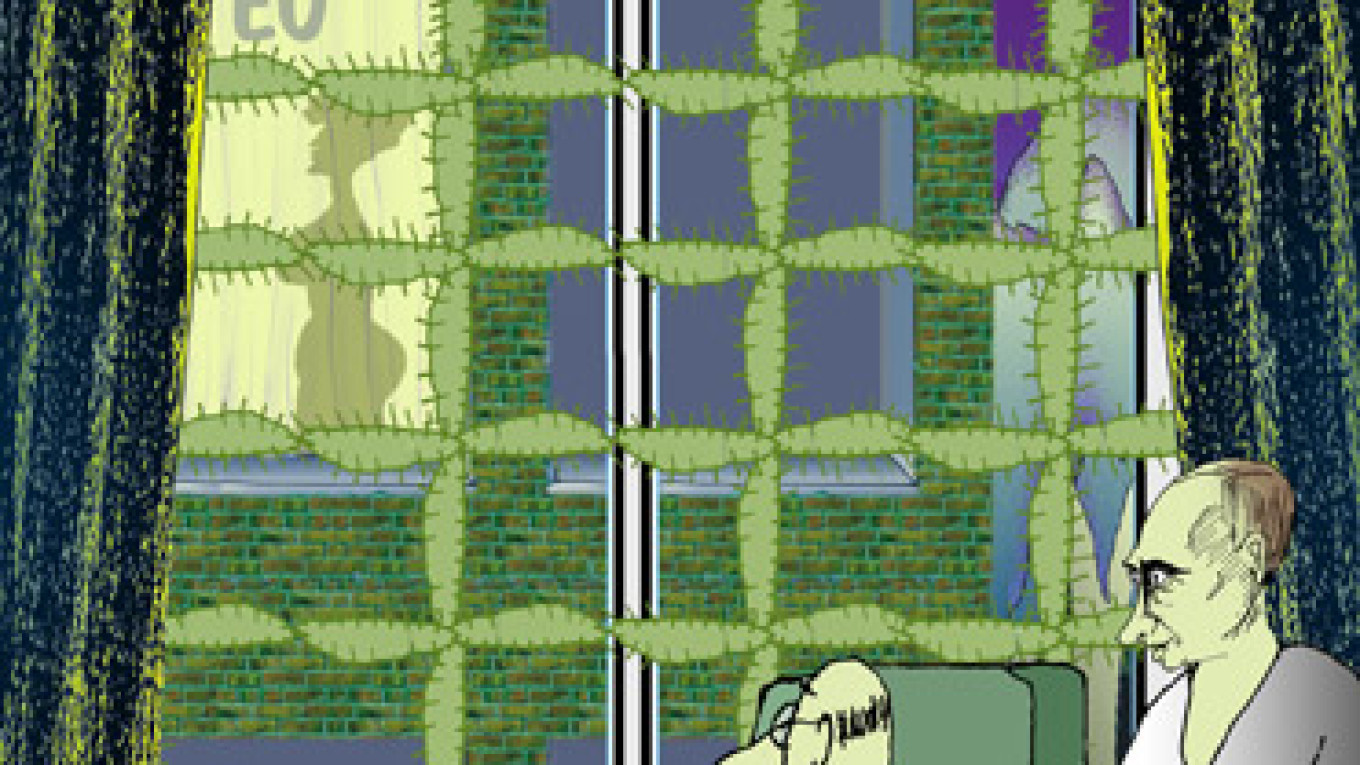

Like Ukraine, Moldova has become a geo-strategic competition between Brussels and Moscow. And like Ukraine, Russia will be determined not to let the country slip away from its influence. As shown during the election campaign, Russia will attempt to use its version of soft power to continue to meddle in Moldova.

Indeed, what the outcome of the elections in Moldova showed was the differences between the soft power tools used by the EU and those used by Russia.

The EU prides itself on its soft power that consists, among other things, of helping build the rule of law, granting financial assistance and development aid, and extending trade-preferential tariffs. In the case of Moldova, it is the very attractiveness of the EU itself that has remained a magnet for the majority of the country's 3.5 million inhabitants.

It is not just about the soft power instruments of trade. It is the sheer fact of bringing Moldova closer to Europe — for example, by allowing visa-free travel that was recently granted to Moldovans.

This kind of soft power should not be underestimated. When the citizens of neighboring Romania — an EU member — were given the right to work anywhere in EU countries, the impact on young people in particular was astonishing.

It was they who during last month's presidential election in Romania queued for hours outside their embassies in London, Paris, Berlin and Madrid to vote. It was they, along with the younger generation back home, who decided they wanted a new direction for their country. They voted for the ethnic German-Romanian, Klaus Iohannis.

This non-charismatic mayor of Sibiu, Transylvania, made the fight against corruption and the need for transparency his election battle cries. After nearly 25 years of misrule, rampant corruption and cynical political elites that took the electorate for granted, Iohannis' victory could now regenerate Romanian politics.

In short, the change in Romania could not have happened without the exposure of a younger generation to working and studying in EU countries. This is probably one of the EU's most important aspects of soft power. Moldovans are now experiencing the chance to compare political and social structures of power.

Russia's own soft power, which it used during Moldova's election campaign, is entirely different. Apart from the fact that Russia supported the well-oiled Party of Socialists machine, and Russia has huge means at its disposal for influencing the media both in non-EU and EU countries, Russia's soft power in Moldova was also based on threats and meddling.

Moldova has already been subject to an extraordinary degree of blackmail and threats by Russia. Just before Moldova signed the EU's association agreement in Vilnius more than a year ago, Russia launched a vitriolic campaign against the EU inside Moldova. It also threatened to impose several kinds of trade embargoes on a country that has been heavily dependent on Russia for its energy, trade and labor market for migrant workers.

Having defied such pressure by signing and later ratifying the EU agreement, Russia has since banned imports of wines, meat and vegetables. Russia too has threatened to cut off its energy supplies and stop Moldova's migrant workers from entering Russia.

Russia's meddling in Moldova has increased in another way too. It is not just in the region of the self-proclaimed republic of Transdnestr where for several years Russian-backed leaders have been trying to break away from Moldova.

Russia is meddling in the region of Gagauzia, southeastern Moldova, which is home to 200,000 Turkic-speaking inhabitants. The community has become increasingly pro-Russian as the Kremlin openly supports their calls for more autonomy, if not independence from Moldova.

The government in Chisinau could have a major separatist movement on its hands, supported by Russia. In a referendum carried out among the Gagauz minority last February, 98 percent voted against Moldova's closer ties with the EU and 92 percent supported Moldova joining the Russian-led Customs Union.

Burdened with the distractions of a frozen conflict in Transdnestr, Russia's support for the Gagauz, and Moscow's economic embargoes, Moldova's incoming government will be hard-pressed to combat corruption and introduce long-overdue reforms. Failure to do so could vindicate Russia's version of soft power.

Judy Dempsey is senior associate and editor-in-chief of Strategic Europe at Carnegie Europe.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.