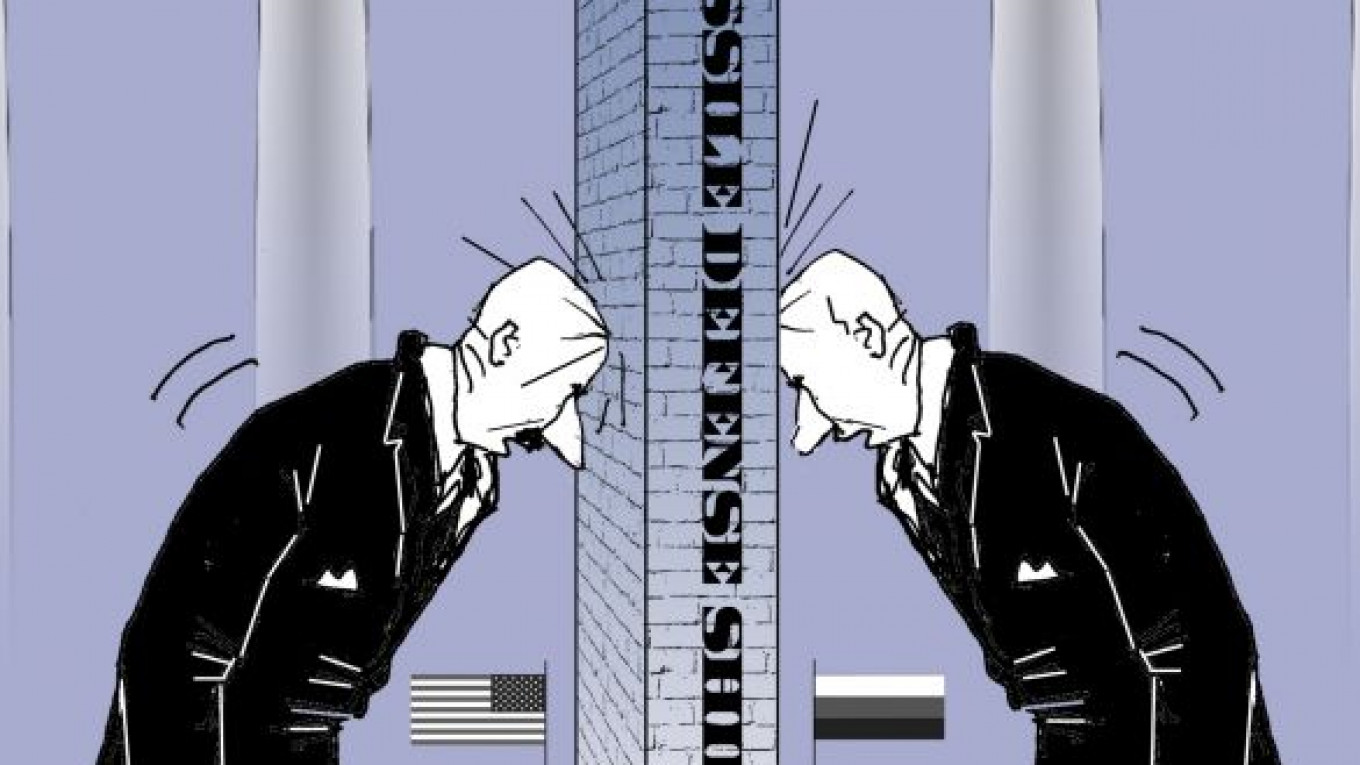

Before President Barack Obama's state-of-the-union address on Feb. 13, two reports emerged from the U.S. whose content was rather unusual, as are the possible political and military consequences.

First, The Associated Press reported that secret studies by the U.S. Department of Defense have questioned the capability of the U.S. missile defense system to be deployed in Europe to protect the country from Iranian ballistic missiles. Apparently, the report was based on data presented recently at a secret briefing of the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Second, The New York Times, quoting an anonymous source within the Obama administration, said Washington would call on Russia to jointly reduce further strategic offensive weapons.

The missile defense report is only partially plausible. Indeed, the U.S. government has been conducting studies to determine the advisability of deploying a European and global missile defense system for quite some time. U.S. operational missile defense systems to be deployed in Romania and Poland in 2015 and 2018, respectively, are not designed to intercept potential ballistic missiles launched by Iran — the reason that the U.S. gave for introducing the missile shield. This is the task of the missile defense systems of the United States and its allies deployed in the Gulf region. The only purpose of the U.S. missile defense equipment deployed in Europe is to destroy Russian intercontinental ballistic missiles.

The fact that our country is never mentioned in the missile shield program as a potential participant proves that it is aimed at Russia. Russia is missing from both the NATO Missile Defense Action Plan and the U.S. and alliance's "rules of engagement" concerning the use of anti-ballistic missiles, endorsed shortly after the NATO Chicago summit last year.

As for the Times report on a further reduction of strategic offensive weapons, it was denied almost immediately by a White House spokesman, who said he was not expecting any new announcements in Obama's speech. Indeed, Obama only said Washington was ready to involve Russia in a "nuclear weapons reduction," without giving any quantitative parameters.

Obama's address failed to answer a principle question for our country: Will the U.S. reduce or build up its missile defense structure in Europe? Russia would also like to know in what maritime areas the U.S. plans to base long-range interceptors. Around 30 U.S. ships have already been equipped with such equipment, and each ship could carry 30 to 40 missiles. Will the U.S. ground-based anti-ballistic missiles, to be deployed at the Deveselu base in Romania and near the Polish town of Redzikovo, be replaced with more capable ones, thus augmenting their capability to cancel out Russian nuclear deterrence forces?

Other questions arise as well. Why do these "new" ideas on strategic weapons reduction put forward by Washington still not mention whether the U.S. will withdraw its tactical nuclear weapons from Europe, as Russia did more than 18 years ago? Does Washington plan to retain weapons of this type on the continent for several more decades, especially as the Pentagon has already announced their future upgrade by 2030? Why has the U.S. Air Force completed building new underground warehouses at 13 air bases in six NATO member countries to store precision nuclear air bombs designed to destroy hard targets? Why do the U.S. and its NATO allies insist on counting the number of Russian tactical nuclear weapons and determining their location and state of readiness before the official discussions on them begin?

Finally, in light of the two news reports, one could ask: Why were they published, and why isn't there any additional information?

Here, it seems, everything is simple. It's obvious that the U.S. intends to go down the road of selectively reducing nuclear weapons, focusing only on a further reduction of strategic offensive weapons. But at the same time, the Americans completely exclude from the negotiations such important non-nuclear weapons as anti-missile systems, anti-satellite weapons and high-precision capabilities that could perform lightning strikes in any part of the world. On top of this, Obama said in his speech that he was willing to "strengthen the missile defense system" during his second term.

This means that the U.S. is floating new arms-control proposals to obscure its far-reaching plans to deploy tactical nuclear weapons and the missile defense shield, destabilizing the global political and military environment and undermining the fragile strategic and military balance between Moscow and Washington that took several decades to establish. For instance, building up combat and data-collection missile defense equipment while reducing strategic offensive weapons could lead to a dangerous situation described by U.S. leaders back in the 1960s and '70s as the nuclear missiles and anti-ballistic missiles arms race. Such an imbalance could tempt the U.S. to launch a first nuclear strike.

This is why, no matter how White House proposals are presented, Russia's defense interests will not be served by a further reduction of its strategic offensive weapons against the background of a U.S. buildup of missile defense capabilities around the world. Russia's updated foreign policy, issued in mid-February, says our country has consistently supported constructive cooperation with the U.S. in the area of arms control, including taking into consideration the unbreakable link between strategic offensive and defensive capabilities and the urgency of making the nuclear disarmament process multilateral. It also assumes that negotiations on a further reduction of offensive nuclear weapons are possible "only taking into consideration all the factors affecting global strategic stability, without any exceptions."

Moscow and Washington should agree once and for all not to use nuclear weapons first against each other and not to deploy their missile defense systems near the borders of the other country. Russia has repeatedly declared its willingness to show restraint in the area of missile defense. A refusal by both sides to use nuclear weapons in a first strike would make the deployment of American missile defense systems at the "forward lines" illogical and set an example of real cooperation for other nuclear states.

Obviously, Russia and the U.S. would maintain their right to deploy and upgrade their infrastructure for the interception of ballistic missiles on their territories.

But Washington should renounce its plans to implement not only the fourth but all the other phases of its current missile defense program. This means calling off the second phase, which has already started, and canceling the third as well. If Washington stops implementation of the fourth phase only, it will not meet the national security interests of Russia. In this case, the U.S. and NATO missile defense system will be deployed anyway.

Quite frankly, instead of thinking how to encircle Russia with nuclear and missile defense weapons, the American side should think about how it can work together with us and other interested parties to prevent meteorites from raining down on our planet.

Vladimir Kozin is a? member of? an interagency working group attached to? the Russian presidential administration discussing missile defense issues with NATO, and? is a? leading researcher with the? Russian Institute of? Strategic Studies.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.