Those who had hoped that President Dmitry Medvedev would lead Russia to a more democratic, Western-friendly future have experienced a roller coaster of emotions recently. They were uplifted by a speech Medvedev gave before Russia’s ambassadors two weeks ago in which he spoke of the need for “modernization alliances” with the United States and other Western countries. Once again, Medvedev voiced support for the rule of law, democracy, and civil society institutions: “It is in the interests of Russian democracy for as many nations as possible to follow democratic standards in their domestic policy.”

Three days later, however, Medvedev’s comments in a joint news conference with German Chancellor Angela Merkel were downright depressing as he took responsibility for a law that would dangerously expand the powers of the Federal Security Service.

The FSB bill was submitted by the government to the State Duma after the Moscow metro bombings in March. Among other things, it will broaden the powers of the FSB to warn citizens that their actions could be a future violation of the law. How law enforcement officials can divine this is anyone’s guess, but one of the substantiated fears is that the bill will be used to intimidate opponents of the government to think twice before they speak or act. After the Duma approved the bill, the Federation Council rubber-stamped it on July 19, and it now goes to Medvedev for his signature.

Russia’s leading human rights activists warned in a recent open letter that the legislation would return the country to “legal tyranny, intimidation of dissenters and control of security services over the peaceful activities of citizens.” They and other opponents of the bill had hoped that Medvedev would veto the legislation, but his comments with Merkel killed those chances. “The law on the FSB is our domestic bill. Every country has a right to improve its legislation, including that related to the special services,” Medvedev said. “What’s going on now — I would like you to know this — was done on my own direct instructions.”

Alas, this is not the only legislation threatening to curtail citizens’ rights. Another bill being considered would ban people previously convicted of offenses — including minor traffic offenses such as speeding — from organizing public rallies and protests. This would give authorities more latitude to reject applications for public gatherings. The Communications and Press Ministry, meanwhile, is pushing for passage of legislation that would grant law enforcement agencies greater discretion and power to shut down web sites and go after Internet providers. Medvedev has been silent on both of these dangerous bills.

But the disappointment with Medvedev extends well beyond his views on specific laws. At the news conference with Merkel, Medvedev responded defensively to the accusation that there has been no progress in the investigation into the slaying of Natalya Estemirova, a brave human rights activist in Chechnya who was brutally murdered a year ago. At the time of her murder, Medvedev promised to bring those responsible to account, and yet nothing has been done. He made a similar pledge concerning Sergei Magnitsky, a lawyer imprisoned on trumped-up charges after he publicly accused Interior Ministry officials of mass corruption. Magnitsky died in jail in November after being deprived of proper medical care. Three ministry officials involved in his case were promoted earlier this year, and no charges have been brought against anyone for Magnitsky’s death. In addition, Medvedev signed a law last year that empowers local legislatures to oust mayors on charges such as mismanagement, neglect of duties or losing the respect of lawmakers. The president also granted new powers to governors to fire mayors. This law makes direct elections of mayors meaningless.

More than halfway through Medvedev’s term as president, the political situation in Russia remains abysmal. The U.S. State Department’s 2009 Human Rights Report gives detailed information about the high number of killings among critics of the government, journalists and human rights activists, most of which go unpunished. In addition, corruption is worsening, rule of law is virtually nonexistent, and the North Caucasus is a hotbed of human rights abuses and terrorism. Amid this lawlessness, the new legislation before the parliament suggests that the government intends to tighten the screws even more, especially ahead of Duma elections in 2011 and the presidential election in 2012.

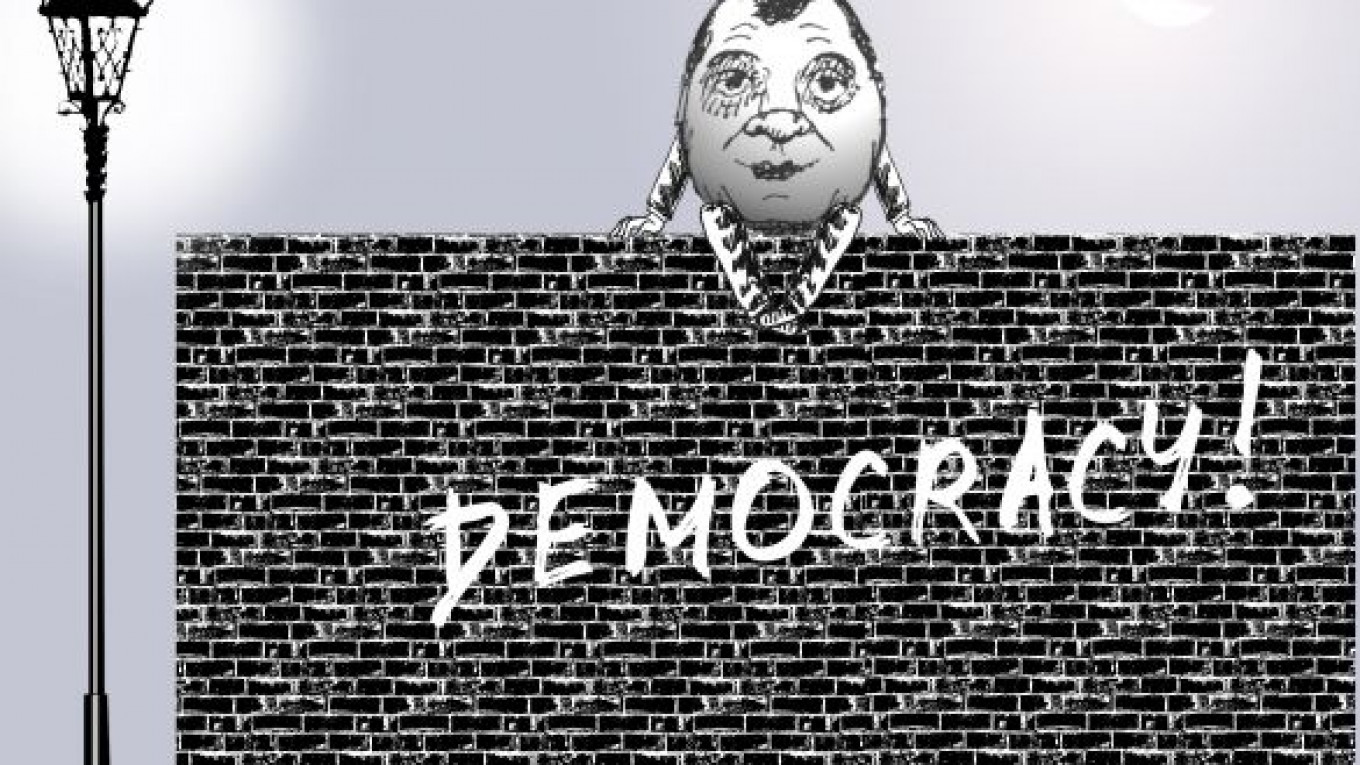

Notwithstanding Medvedev’s occasionally lofty rhetoric and his gentle face to the West, Russia under his presidency continues to move in an authoritarian direction. That reality is difficult to square for those who want to believe in Medvedev’s speeches, including the Orwellian-like one he gave at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in June where he said Russia should become a country that would attract people from all over the world “in search of their special dreams, success and self-fulfillment.”

David J. Kramer is senior trans-Atlantic fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States in Washington. During the administration of George W. Bush, he served as deputy assistant secretary of state for Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. He writes here in a personal capacity.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.