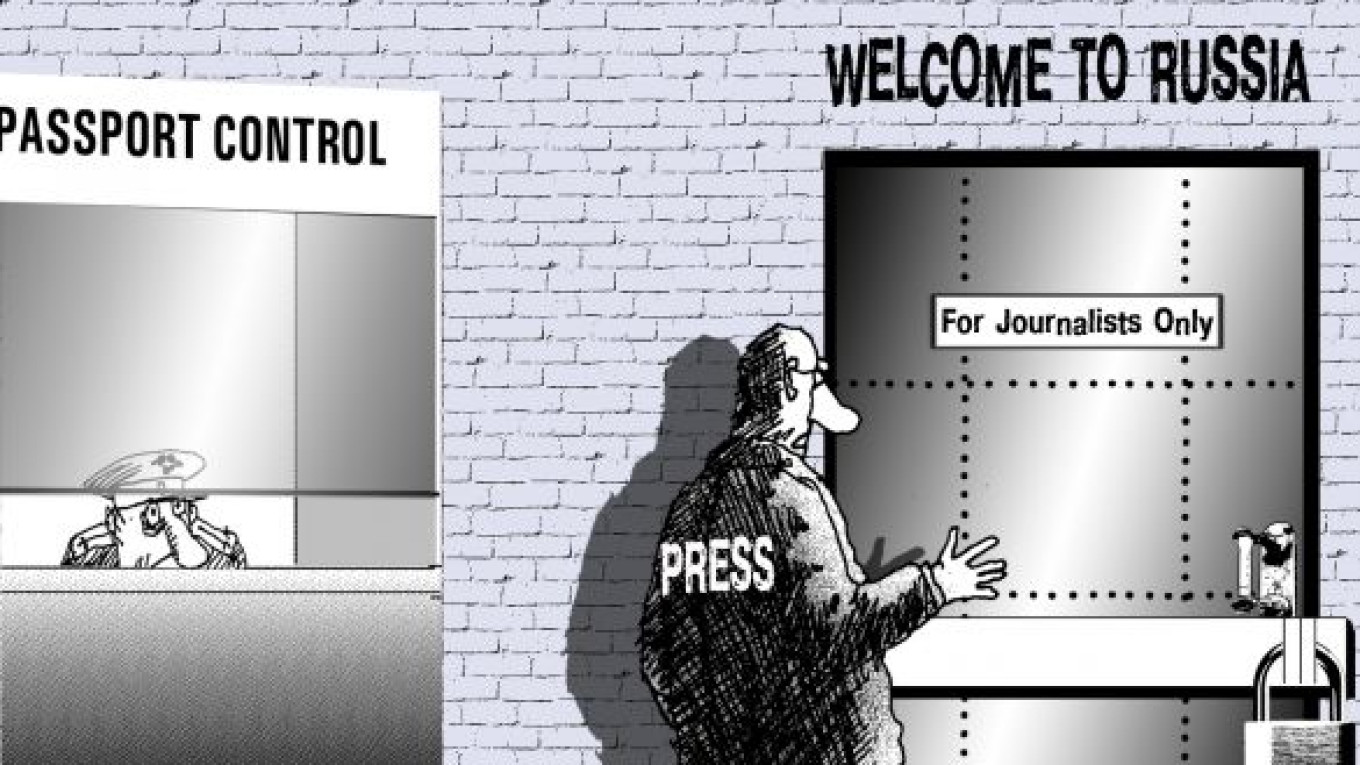

The Kremlin once again showed its true appreciation for freedom of the press by expelling British journalist Luke Harding, the Moscow correspondent for The Guardian, on Saturday.

The Foreign Ministry explained on Tuesday that Harding had violated the accreditation rules for foreign journalists. According to a ministry statement, "Having received in the end of November 2010 an extension for his accreditation, Harding left Moscow for London without taking the accreditation letter for foreign journalists that was issued for him, although he knew about the necessity of doing so."

This is hardly a compelling reason for why guards from the Federal Border Service, an arm of? the Federal Security Service, arrested Harding at Domodedovo Airport after he arrived from? ?London, annulled his visa on the spot and forced him to return to London on the next flight.

Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said Harding repeatedly traveled to parts of Russia where counterterrorism operations were under way without notifying security services, RIA-Novosti reported. Harding denies these allegations. Whatever the case, any journalist who has traveled to the North Caucasus can confirm that few oblige by these rules, which have been in place since 2004, for fear of being unlawfully obstructed by the siloviki. Since no journalist has had his visa annulled on these grounds, the logical question is why are they being applied selectively to Harding?

Harding's explanation for his expulsion is much more convincing — that it was related to his articles about WikiLeaks cables that speak about corruption among top officials and Russia as a "mafia state," something that clearly irritated either the FSB or the Kremlin or both. Although other newspapers ?€” such as The New York Times, El Pais and Le Monde ?€” analyzed the same cables, they were written by reporters who were not located in Moscow.

The other likely explanations for Harding's expulsion is his Dec. 1 article, referencing WikiLeaks cables, that then-President Vladimir Putin likely knew about the plans to kill former FSB agent Alexander Litvinenko before he was poisoned in London.

In addition, Harding wrote an article in 2007 about allegations that Putin's net worth may be at least $40 billion, referring to political expert Stanislav Belkovsky's earlier interview in Die Welt. Since then, however, this claim has been repeated in several newspapers, including The Moscow Times.

In all likelihood, Harding, who has been based in Moscow since 2007, was singled out arbitrarily as a fall guy to intimidate other foreign journalists working in Russia. The message the Kremlin and FSB want to send seems clear: If you write about sensitive issues, such as corruption among top officials or other government abuses, you could be kicked out of the country.

Every autocracy strives to enforce self-censorship any way it can. After all, self-censorship is a lot "cleaner" and more subtle than the clumsy and crude government-enforced censorship. When successfully implemented, it is self-regulating and requires little maintenance, apart from expelling a foreign journalist every now and then to remind everyone they that are guests in a country that doesn't take kindly to criticism ?€” foreign or otherwise.

Apparently, the Kremlin's notion of the ideal foreign journalist is former New York Times Moscow bureau chief, Walter Duranty ?€” the quintessential "useful idiot" who self-censored himself so much that he denied the Soviet famine of 1932-33 in his articles published in 1933 in an apparent attempt to please Stalin.

Harding's expulsion is reprehensible, but it is by far not the only such case since Putin came to power. According to the Moscow-based Center for Journalism in Extreme Situations, more than 40 foreign journalists were refused entry to Russia between 2000 and 2007.

In one of the best-known cases, New Times journalist Natalya Morar, a Moldovan citizen, was expelled in December 2007 after writing about the Kremlin's slush fund to support friendly political parties and money-laundering allegations against top Kremlin officials, including now-director of the FSB, Alexander Bortnikov.

When Morar's case was reviewed by the ??onstitutional Court in 2009, the court referred to a provision in a law on denying entry to Russia when it affects "state security." Apparently, freedom? of the press and investigative journalism against corruption are direct threats to the security of Putin's vertical power structure.

When Harding was denied entry after trying to pass through passport control with a valid visa, an airport security official told him, "For you, Russia is closed."

Very well put. Russia truly is a closed society ?€” and not only for Harding. If the Kremlin continues to expel foreign journalists who write about corruption and other government abuses of power, Russia will close itself off not only from that irritating, insolent institution called the Fourth Estate, but from foreign investors and the entire Western democratic world as well.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.