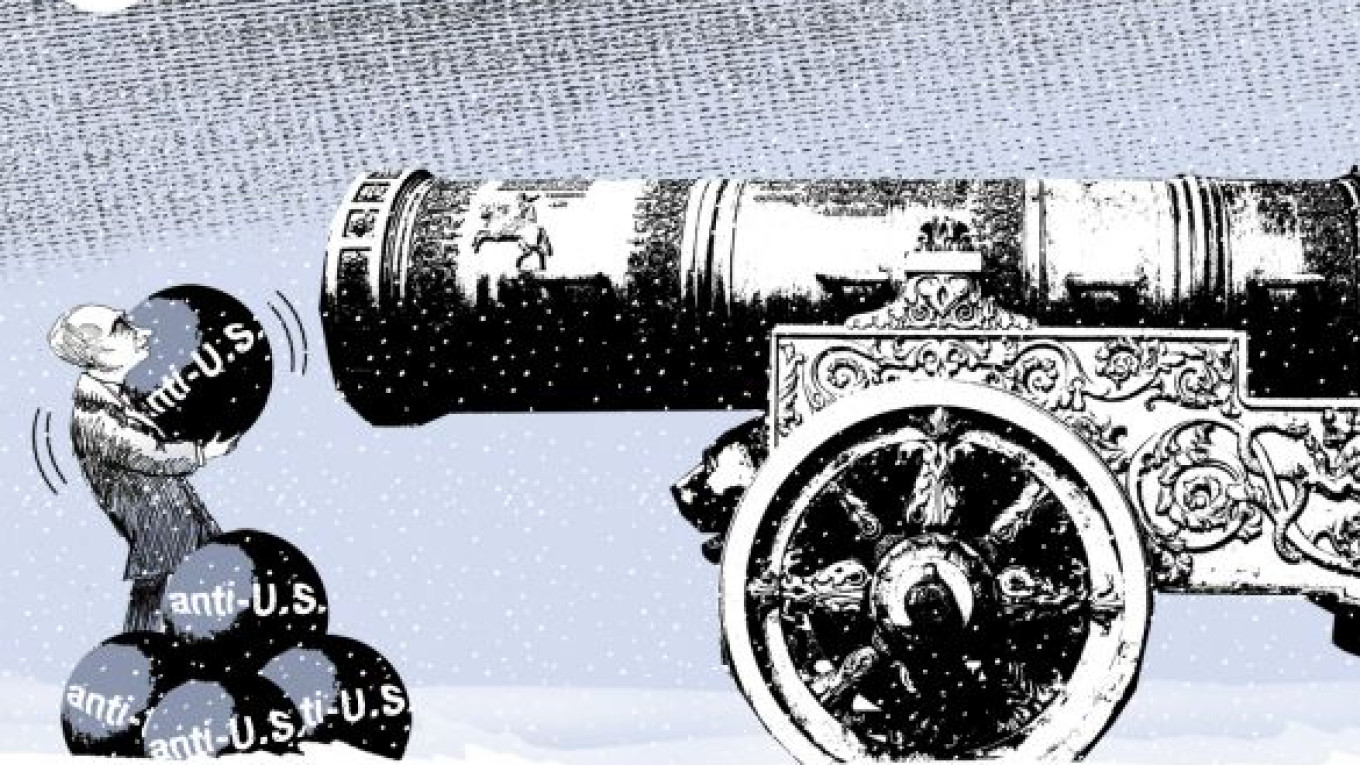

An increase in anti-Americanism stands out as one of the most dominant features of the Kremlin's policy in 2012. Since the propaganda campaign worked so effectively on many Russians, we can expect even more state-sponsored anti-Americanism in 2013.

The first anti-U.S. salvo was fired after Michael McFaul arrived in Moscow in mid-January 2012 as the new U.S. ambassador. Pro-Kremlin political analysts and a dozen pseudo-?documentaries on state-controlled television, such as warned Russians throughout the first six months of the year that McFaul, a renowned academic expert in democratic revolutions, had been sent by Washington to help orchestrate an Orange-style revolution.

The second large salvo was fired in July, when Putin signed the law forcing "politically active" nongovernmental organizations that receive foreign money to register as "foreign agents." Then in October, ?USAID, the largest source of funds for Russian NGOs, was forced to close its Moscow office.

The 2012 anti-U.S. campaign peaked on Dec. 28, when Putin signed the "anti-Magnitsky act" that bans all U.S. adoptions of Russian children. Pavel Astakhov, the children's rights ombudsman, tried to justify the legislation by claiming that U.S. abuse and neglect of Russian children is rampant, while State Duma Deputy Svetlana Goryacheva said 10 percent of adopted children — or 6,000 — have been tortured or used for organs transplants and sexual exploitation in the U.S. The message the Kremlin and its servants sent was clear: Most U.S. adoptive parents are psychopaths and sadists, while Russophobic U.S. courts cover up their crimes.

What's more, Article 3 of the anti-Magnitsky act allows Russia to suspend activities of NGOs if they receive money from U.S. citizens and "present a danger to the interests of Russia." Before, only funds sent by the State Department were considered subversive; now private donations from U.S. citizens are considered subversive as well. After all, the argument goes, secret agents of the State Department could pose as private citizens, so it's better to ban all U.S. donations to Russian NGOs to be on the safe side.

The Kremlin's hard work on the anti-American front seems to have paid off. A December poll conducted by the Public Opinion Foundation indicated that 56 percent of Russians support the law banning U.S. adoptions. Presumably, respondents bought the Kremlin line that Russian children are more at risk in U.S. homes than in Russian orphanages. In addition, a recent VTsIOM poll found that 64 percent of Russians oppose foreign-funded NGOs. Furthermore, 23 percent believe Putin's and state-television's version of events — that Moscow protesters were paid by the U.S. to rally in the streets — while 47 percent had difficulty knowing who to believe, according to a Levada Center poll in March. By the end of 2012, Levada found, the percentage of Russians who had a positive attitude toward the U.S. had dropped to 46 percent from 67 percent a year earlier.

These results show that anti-?Americanism remains a tried-and-true method for President Vladimir Putin to boost popularity among his conservative constituency and to shift attention away from Russia's own problems onto a mythical enemy.

For these reasons, the anti-U.S. campaign will likely continue in 2013 and perhaps even intensify. The Kremlin could focus on the following three measures:

1.? A crackdown on U.S. journalists

Andrei Lugovoi, a Liberal Democratic Party deputy whose only claim to fame is being implicated in the polonium murder of Alexander Litvinenko in London, has co-authored a bill that would ban journalists who have foreign citizenship from working on state television if they criticize Russia. The idea was borne after legendary journalist Vladimir Pozner referred to the State Duma as the State which means "fool" in Russian, during his Dec. 23 weekly television program on Channel One. Seemingly offended by the slight, Lugovoi said Pozner, who holds U.S. and French citizenship, had no right to "discredit" Russia with such statements. (Notably, the ban would only apply to foreign journalists who criticize Russia; if a Russian journalist made the same criticism, presumably this would be a lesser crime.)

The next logical step would be to target Russia-based U.S. journalists who also "discredit" Russia by criticizing the Duma and other government institutions and Putin and other government officials. After all, these journalists could be secret U.S. agents and part of a larger State Department plan to defame Russia. By producing "anti-Russian" reports, the argument goes, U.S. journalists mobilize global opinion against the Kremlin and provide the ideological and propagandistic foundation for the opposition and its U.S. sponsors to stage a revolution.

To these ends, United Russia Deputy Yevgeny Fyodorov has sponsored another "patriotic bill" that would require "politically oriented" media outlets that receive more than 50 percent of their financing from foreign sources to register with the Justice Ministry as "foreign agents."

Alexei Pushkov, head of the Duma's International Affairs Committee, helped lay the groundwork for these initiatives, saying during an Oct. 22 Duma hearing on U.S. human rights violations that the U.S. media "act as the ideological hand of the United States … and serve the political interests of the government."

The government's crackdown on U.S. journalists could take the simple form of denying them Russian visas. It could also force the foreign-funded media outlets that they work for to shut down by prosecuting them on trumped-up charges of tax evasion, extremism or defamation, the latter of which was recently returned to the Criminal Code.

2. A ban on U.S.-Russian marriages

Fyodorov, the United Russia deputy, submitted another bill that would forbid government employees from marrying foreigners. He believes that having a foreign spouse is much like owning foreign real estate: Both raise questions of loyalty to the motherland and should be outlawed.

Fyodorov's idea is not new. In 2005, the Liberal Democratic Party submitted a broader bill that would forbid all Russian women from marrying foreign men, mirroring a Josef Stalin law from 1947. LDPR's concern was that the U.S., the largest destination for young Russian women who marry foreigners, was "stealing" the country's most beautiful women and ruining the country's gene pool. The bill went nowhere, but with a renewed focus on Russia's demographic problems and anti-Americanism, the Duma could easily revive this initiative in 2013. Just like the adoption ban, which was packaged as a way to stop "selling" Russian children to abusive U.S. parents, a marriage ban could be spun as a way to stop "selling" Russian brides to lecherous American men.

3. A ban on U.S. scholarships for Russian students

Much like "buying up" Russian brides, the Kremlin may also be concerned that the U.S. is buying up Russia's most-talented students by giving them full scholarships and stipends to study in U.S. universities. After graduating, most Russian students stay in the U.S. and make value contributions to the U.S. economy, not Russia's. They then marry Americans and give birth to a new generation of talented Russian-Americans.

But the Kremlin also fears that the small number of students who return to Russia could spread the "pernicious, bourgeois" values they acquired in the U.S. Yet the danger goes even deeper than this. As we learned from NTV's "Anatomy of a Protest" program, the U.S. government used an academic scholarship to lure Alexei Navalny to Yale University in 2010, where he was supposedly recruited by the CIA to become the next opposition leader and carry out a revolution. If left unstopped, some believe, the U.S. government could use these scholarships to create a whole army of new opposition leaders and functionaries.

It is clear that Putin, together with his loyal Duma deputies and television networks, is constructing a large propagandistic "Berlin wall" around Russia in his new cold war against the United States.

Mr. Putin, tear down this wall.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.