The news that Prime Minister Vladimir Putin will run for president next year may have finally quashed the dying hopes of the stalwart optimists who, despite all evidence to the contrary, hoped that President Dmitry Medvedev would restore Russian democracy. But it did not forestall the emergence of the newest fantasy about Russian politics: a revamped, more liberal “Putin 2.0.”

This twist fits an old pattern among Russia analysts and journalists, apparently driven by a need to say something new and different about an essentially unchanging reality. More than simply misguided, it is dangerous because it plays into the Kremlin’s strategy for misleading the world about its workings and motives.

Even before Putin stepped down at the end of his first presidential term limit in 2008, the likeliest scenario was that he would remain supreme leader after the meek, loyal Medvedev completed his first term. Nevertheless, many scholars, journalists and pundits in Russia and abroad have spent the past four years arguing the opposite by speculating about when Medvedev would actually assume the vast powers of the presidency.

But when Medvedev finally announced last month that he would step down, new speculation began — this time about the nature of Putin?€™s future rule ?€” without a pause for reflection about why so many chose to ignore the overwhelming evidence that Medvedev was no more than a cog in the Putin regime.

Never mind that Medvedev never appointed a single important minister or even his own domestic and foreign policy advisers ?€” they were all Putin?€™s men ?€” during his presidential term. Never mind that his impossible-sounding exhortations to modernize Russia sharply contrasted with how far backward the authorities were actually driving the country by cultivating authoritarianism and corruption. Never mind that Putin?€™s personality cult regularly ballooned with every one of his bare-chested publicity stunts.

Now that there is no longer any dispute that Putin will almost certainly remain Russia?€™s indisputable autocrat for longer than any leader since Josef Stalin, some are earnestly asking whether he will return to the presidency as the ?€?reformer?€? of his first term as president a dozen years ago. Putin encouraged such sentiment this week by reviving the myth that Russia could face ruin by turning away from its current course.

?€?They say that things can?€™t get any worse,?€? he said in a joint interview to the heads of the country?€™s top three government-controlled television channels, recorded Saturday and broadcast Monday evening. But it?€™s enough to take two or three incorrect steps. We lived through the collapse of the country. We lived through a very difficult period in the 1990s. Only in the 2000s did we begin to get to our feet.?€?

Of course, Putin was never a reformer ?€” at least the democratizing kind the West pined for. At the very start of his tenure, he shut down the best of the country?€™s independent national television stations, cancelled direct elections for Federation Council members, jailed opponents and intimidated Russia?€™s business barons with tax investigations that were dropped as soon as they ensured loyalty.

What he did do with his growing power was to push through a small handful of economic reforms that had been stifled by the Communist opposition under former President Boris Yeltsin: a flat tax rate and land reform chief among them. That was enough to earn him the title of ?€?reformer.?€? Otherwise, his crippling of the country?€™s judiciary and legislative institutions and directing the forced nationalization of the oil and other industries did far more to offset the benefits of any liberalizing policy. It was high energy prices that were chiefly responsible for resuscitating the country?€™s economy in the 2000s.

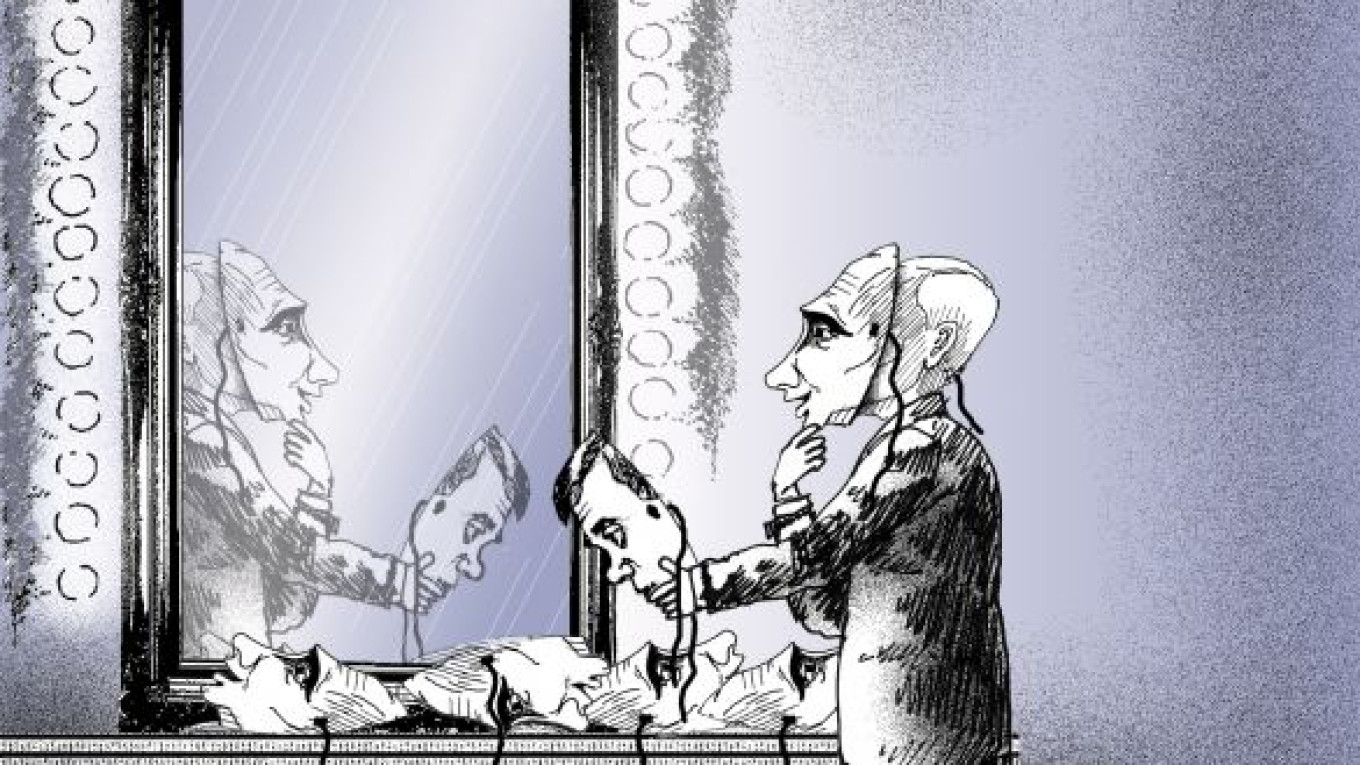

Enter Medvedev, whose promises to fight corruption four years ago did nothing to check its rise. The main lesson we should have learned from his presidency is that his liberal persona and promises of reform were really part of a ruse. Many fell for it, disregarding a central trope in the traditional political culture Putin has restored: politicians?€™ rhetoric and the facade of institutions are meant to obscure how Russia is really ruled.

Of course, journalists feel pressured to come up with fresh angles. Everyone is sick and tired of hearing about Russian authoritarianism, so the temptation to publish positive news for a change is understandable. But the desire to engage readers does not make wishes true. Nor does speculation about the Kremlin?€™s inner workings in the absence of real knowledge about them.

Wishful thinking about Russia also reflects a particular Western philosophical nature. With almost 40 percent of Russians now logging on to the Internet, surely they will understand the improvement in quality of life that democracy brings and stop supporting their autocrats, the conventional argument goes. But Russians are logging on to Facebook and Angry Birds, not The New York Times.

Let?€™s not kid ourselves about Russia. There is no evidence that Putin is a reformer, but there is a lot of proof that he is a power-hungry autocrat who is not about to change as long as high prices for oil and gas support his patronage system. Projecting our wishes based on the latest fantasy about Putin?€™s rule is just what he wants, and it does us all a disservice.

Gregory Feifer, a former Moscow correspondent for National Public Radio, is a senior correspondent for Radio Free Europe. He is writing a book about Russian behavior and society.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.