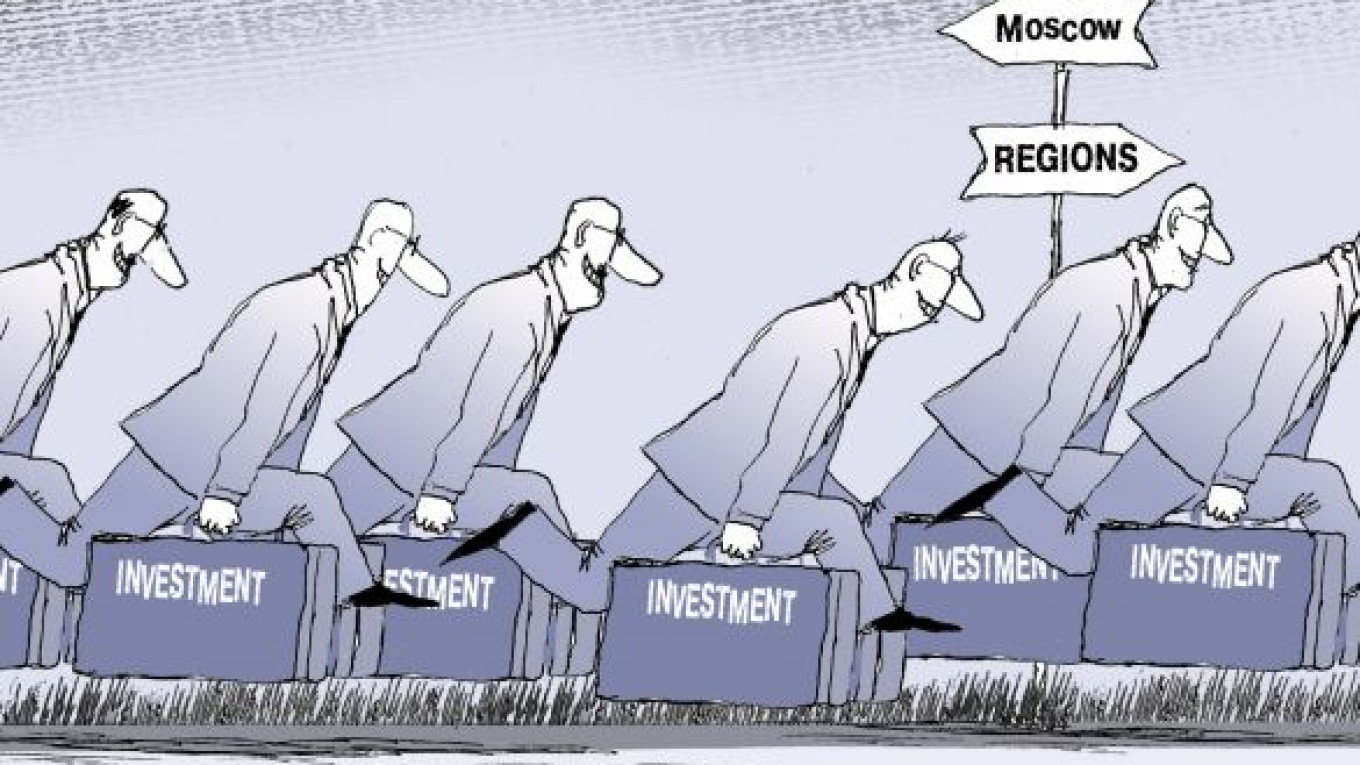

Moscow has historically absorbed the bulk of investment and development in Russia — no one was surprised to learn that more than 90 percent of domestic investment wound up in Moscow in 2010. But there are several signs that business’s overwhelming preference for Moscow is coming to an end. Moscow’s overloaded infrastructure, new authorities with a different set of priorities, and exorbitant costs of living and doing business all are factors that are prompting businesses to explore Russia beyond Moscow.

As a result, over the next 10 years we expect a drastic reduction in the influx of labor from the regions to Moscow. Due to a combination of market forces and prudent policies, by 2020 the economy will be far more modern, expanding more evenly across the regions. As a result, the capital itself will become a far more livable city — and thus more competitive as a global financial center.

Moscow’s uncontrolled growth into an expensive, overcrowded metropolis with overtaxed infrastructure is part of a natural process that most developed countries have experienced. The market-based reaction away from the metropolis to more affordable cities with better quality of life is equally natural — and it’s about to begin in Russia.

New York was once the dominant city for business in the United States. But it became so crowded and expensive that many industries left it for New Jersey or Los Angeles. In the 1990s, Los Angeles went through the same process. Today the U.S. economy is spread out across more than 20 major cities, many hubs for specific industries.

As Russia enters a new era of modernization, the move beyond Moscow has already begun, led by the most economy’s most innovative sector: IT. At least 12 major IT companies have developed or relocated their research divisions to regional cities, including Accenture in Tver; Hewlett-Packard in St. Petersburg; Oracle in St. Petersburg, Novosibirsk, Tolyatti and Ryazan; and Intel in St. Petersburg, Nizhny Novgorod and Novosibirsk.

Why? The key factor is the ability to hire and retain workers who have the training and education that the business needs.

As HR professionals know, the best hires often come from strong institutes in the regions. These schools turn out specialists with skills to match their Moscow counterparts — but with initially lower salary expectations. Once they’re in Moscow, however, the many growing competitors make retaining them an expensive prospect.

Much cheaper is for a business to set up or expand in a regional city, next door to the institute that produces the specialists it needs — with no competitors nearby and cheap real estate.

How does it look from the employee’s standpoint? The traditional path to success for talented young Russians is to move to the big city — Moscow — because there are no good jobs available at home.

But the employee’s housing prospects significantly improve once the industry moves to his region. With 70 percent of a Moscow salary, a college graduate can afford a mortgage in his home town, where an apartment is three times cheaper than in Moscow. Kaluga, for example, has a market of more than 125,000 creditworthy buyers, including 25,000 employed at the region’s growing modern industrial parks.

Many businesses locate in Moscow to be near their clients. For the financial services, legal and consulting industries, most clients will always be in Moscow. For other industries, including oil, natural gas and pharmaceuticals, the government is either a partner or regulator, or both.

For most businesses, each function has its own set of factors that determines its optimal location. Most manufacturing functions need to be near abundant, cost-effective labor, not near the customer — except where logistics costs represent a high proportion of total product cost. Some need to be near cheap raw materials. Almost all need access to cheap, reliable utilities.

Accounting and finance, customer service, repair, training and many HR functions do not have to be near their internal or external clients. Thus, in 2008 Alfa Bank acquired a former factory building in Ulyanovsk and redeveloped nearly 7,500 square meters for support functions. Citibank purchased 6,000 square meters in Ryazan.

In another case, a major audit firm has decided to be close to major clients by basing audit teams in the regional cities where the resource-extracting corporations are based.

Historically, the shift from overgrown cities to the regions takes place when changing conditions start creating a better business and living environment in other places. Clearly the factors are there to push business out of Moscow, and now the government seems to realize that endless growth is bad for the city and Russia as a whole. Indeed, for Moscow to perform effectively as a modern international financial and decision-making center, it will benefit from less demand on its infrastructure and competition for its workers from industries and business functions that can be more economically effective in other regions where more investment is needed.

So what do the regions need to have to “pull” businesses in and retain their talented young people? The risks and costs for business must be favorable compared with those in Moscow, as must the affordability and quality of life for individuals.

Risks are reduced and costs become clear when real estate infrastructure is in place: roads and utilities for factories; roads, electricity and fiber optic capacity for offices. Regions that are delivering these in a transparent process free of corruption are winning the investment of businesses in Russia.

Kaluga has become the leading example. Four industrial parks created with infrastructure financed by the government with a loan from VEB, combined with the transparent, hands-on approach of the team led personally by Governor Anatoly Artamonov attracted more than $5 billion in investment and created a pipeline of more than 25,000 new jobs.

At a recent meeting, Artamonov explained that his region is now focused on addressing issues of growth rather than of stagnation. New business has created demand for higher standards of infrastructure, including housing, hotels, education and medical care. These are the things that improve the quality of life for young talented professionals and their families — and will make them choose places like Kaluga over Moscow in the long term.

In Kaluga and Ryazan, the recent influx of well-paid labor has already created shortages in apartments, prompting residential developers to invest in new housing projects.

Meanwhile, mortgage affordability is the crucial factor for increasing mobility. The government understands this and is working on structural factors that enable banks to offer lower interest rates and longer payback periods.

Thus, the process we are observing is an iterative one. As major companies open offices and factories in the regions, the growing professional work force is creating demand for a wide range of modern services. This demand in turn represents an opportunity for service industries, which require their own real estate and other infrastructure and create more jobs — and thus the upward economic spiral is set in motion.

As more regions figure out how to take the first critical steps to get the right infrastructure in place, they too are attracting businesses that can persuade local talent to stay home instead of moving to Moscow.

That is why companies should not wait for Russia to modernize before they take the plunge into the regions. It’s their plunge that will accelerate the modernization of Russia.

Darrell Stanaford is managing director for CB Richard Ellis in Russia.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.