NATO-Russia cooperation is stuck halfway between Cold War antagonism and what NATO Secretary-General Anders Fogh Rasmussen calls “a true strategic partnership.” But there remains a window of opportunity to ensure pan-European security. All parties should bear in mind that trust, inclusion, equality and compromise between Russia, the United States and Europe are key prerequisites for reaching an accord on joint missile defense.

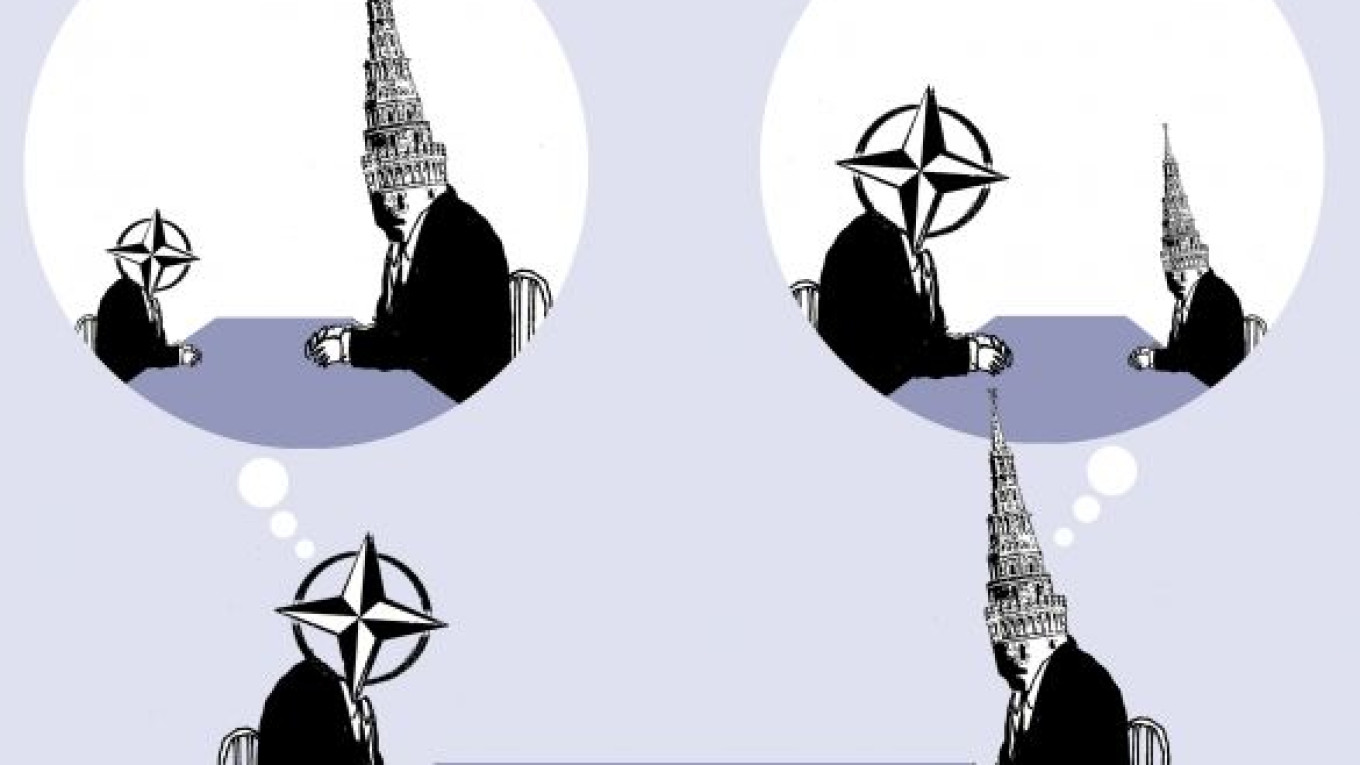

Although NATO and Russia agreed that they pose no threat to each other during the NATO-Russia Council meeting in Lisbon in December, cooperation is still constrained by mutual suspicions and the heavy legacy of history. Clearly, the collapse of the Soviet Union did not automatically establish mutual trust. Although history cannot be rewritten, is there no chance to break the deadlock in NATO-Russia relations and move from a Cold War-era discourse to a truly equal and productive partnership?

Obviously, the elephant in the room in NATO-Russia relations is cooperation on missile defense. No breakthroughs on this topic were reached in numerous meetings of top Russian and NATO officials this year. Unsuccessful attempts by both sides to come to terms with the other’s perception of missile defense cooperation led to Russia’s refusal to accept NATO proposals to set up two independent but connected antimissile entities that would exchange data on missile threats. NATO, meanwhile, did not agree to Moscow’s proposal, which provided for the establishment of a single system that gives both sides equal authority in decision making and interceptor launches. In his speech in London on June 15, Rasmussen explained NATO’s position by stating, “We cannot outsource our collective defense obligations to non-NATO members.”

An agreement on missile defense is not merely a matter of security. One should not underestimate the huge political significance underpinning any agreement on this topic. As Dmitry Rogozin, Russia’s envoy to NATO, recently acknowledged, deep cooperation on missile defense between Russia and the United States is possible from a military and technical angle, but the success of a joint initiative depends on the political readiness of both parties.

Earlier this summer Rogozin said: “Any attempts by those in NATO who dream of neutralizing our strategic potential will be futile. … We have enough capacity to create both defensive and offensive means to counter any missile threat and to penetrate any missile defense.” Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov then claimed that the absence of joint NATO-Russia missile defense “could lead the Kremlin to embark on a weapons buildup.” Such bellicose rhetoric is exacerbated by both parties’ unwillingness to compromise and drags NATO-Russia cooperation back to square one.

Why does the creation of joint missile defense play such a big role in NATO-Russia relations? Vagif Guseinov, an analyst with the Institute of Strategic Studies and Analysis, voiced a popular sentiment when he said Moscow is afraid to be excluded from the decision-making process on joint missile defense or, in the best case, be relegated to an insignificant role.

An agreement on joint missile defense can significantly improve and foster cooperation between NATO and Russia over time, according to a recent survey of Russian experts conducted by atlantic-community.org. The biggest component missing is political will, as well as lack of trust and equality in the partnership. This opinion is shared by almost a third of the Russian experts surveyed. Another fear is that U.S. missile defense might be directed against Russia or its interests and thus suppress its strategic or nuclear potential. In this light, the main preoccupation appears not to be the threat of NATO attacking Russia directly, but rather the fear of a shift in the balance of power in the partnership toward NATO, decreasing Moscow’s strategic potential.

In the survey, Nadezhda Arbatova of the Institute of World Economy and International Relations suggests that one way to improve NATO-Russia security cooperation might include “deep conventional arms and tactical nuclear weapons reductions, which would totally remove any war planning or training of NATO and Russia against each other … and air defense technical projects, starting with the integration of early warning systems.”

Despite Rasmussen’s calls for Russia “to focus on real security challenges instead of some ghosts of the past that do not exist any longer,” it is likely that, without NATO’s legal guarantee and readiness to make concessions in negotiations with Russia, the initiative will bring little long-term success.

Thus, to avoid missing the existing window of opportunity to reset NATO-Russia relations from a vague interim to a clear partnership stage, the parties should bear in mind that trust, inclusion and equality between Russia, the United States and Europe and an ability to compromise for the sake of common pan-European security are the main preconditions for reaching an accord on joint missile defense.

Victoria Naselskaya is the editor of .

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.