The terrorist attack in Boston was an intelligence failure for both Russia and the U.S. It turns out that the Federal Security Service had information about Tamerlan Tsarnaev's suspicious activities but did not even question him when he visited Dagestan for six months in 2012. The FBI received its initial lead on Tamerlan from the FSB in 2011 and even brought him in for questioning, but then forgot about him completely until the day of the bombing.

Apparently, the FSB first took notice of Tamerlan when he began frequenting extremist Islamic websites. It sent a request to the FBI for more information on him. When the FBI had nothing significant to offer, the FSB dropped the case, not even bothering to send the same request to Makhachkala, where relatives of the Tsarnaev family lived. According to available information, not a single member of the Tsarnaev family in Dagestan was questioned in 2011 or in 2012, the year of Tamerlan's visit. Similarly, the FBI issued a request to Lubyanka for additional information on Tamerlan, but, hearing nothing back, it also dropped the case.

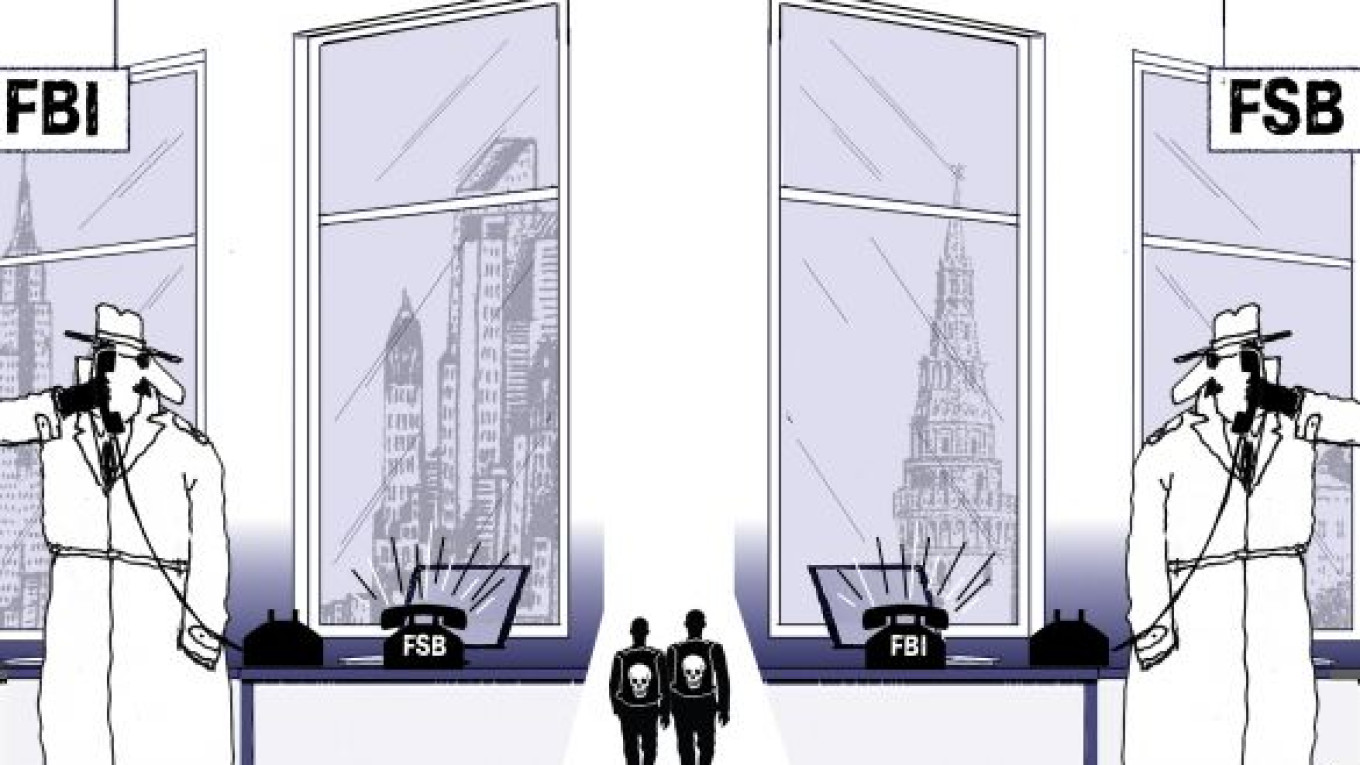

This case underscores the lack of coordination between the FBI and FSB that has all too often hampered cooperation on fighting global terrorism in general.

The FSB contacted the FBI in 2011 with the self-serving goal of obtaining additional information on Tamerlan's activities. The FSB had no intention of alerting the U.S. to a potential terrorist threat, perhaps because it also didn't see a threat.

The failures of both the FBI and FSB show the lack of coordination that has hindered the joint battle on terrorism.

One of the FSB's largest blind spots in fighting terrorism is that it has historically focused on finding ties between suspected terrorists and organizations known to provide individuals and groups with the funding, training, weapons and explosives needed to carry out attacks. In this case, the FSB apparently had no evidence that the Tsarnaev brothers had ties to the underground insurgency in the North Caucasus. (This was later supported when Dagestan militants posted a statement on their websites on Sunday announcing that they had no involvement in the Boston attack and are not at war with the U.S.) Based on an outdated, narrow approach to fighting terrorist groups, the FSB pays little attention to "lone wolf" terrorists like the Tsarnaev brothers. This proved a fatal flaw in the way the FSB downplayed the threat when it contacted the FBI in 2001.

At the same time, however, U.S. intelligence had begun focusing on the "lone wolf" terrorist threat since 2010, after a 30-year-old Pakistan-born U.S. citizen tried to set off a bomb on Times Square. (The bomb was ignited but failed to explode.) In December of that year, Michael Leiter, director of the National Counterterrorism Center, reported to the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington that individual U.S. citizens inspired by radical ideas they had encountered on the Internet were a new form of threat. Only five days earlier, the FBI had arrested Mohamed Osman Mohamud, a 19-year-old U.S. citizen from Somalia who had written three articles on the Jihad Recollections site before attempting to detonate a car bomb in Portland, Oregon.

Accordingly, U.S. intelligence agencies began investing significant resources into tools for conducting surveillance of the Internet and social networks. For example, the FBI initiated a program to monitor social networks in 2012 that is designed to gather information from public sources, identify threats and incidents and determine their physical location. According to the FBI, that system monitors all openly accessible information on social networks based on key words such as "bomb," "white powder," "suspicious bag" and other key words. That information is then processed by the FBI's Strategic Information and Operations Center.

What's more, since 2010, the Department of Homeland Security has also been monitoring such social networks as Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, YouTube, LinkedIn as well as individual blogs. Last year, Homeland Security initiated a new program for monitoring social networks that analysts consider to be even more powerful than the system used by the FBI. The program searches for 380 key words that are categorized by not only such subjects as "terrorist," "jihad," "suicide attack" and "conspiracy," but also "the weather" and "cyber security."

Even the YouTube page that Tamerlan created should have immediately sent up red flags for U.S. intelligence agencies. It includes songs by the famous Chechen bard Timur Mutsurayev such as "I Devote my Life to Jihad," which many Russian courts have banned as being extremist. Tsarnaev also uploaded "Call to the Militia" by Amir Rabbanikal Abu Dudzhan, the leader of a militant group in Dagestan. Many militant websites, including the KavkazCenter, regularly post reports on the activities of Abu Dudzhan's group. What's more, several videos that Tsarnaev posted on YouTube were removed by Google for their extremist content, which alone should have been enough to alert the FBI.

But for some reason, the FBI did not pick up on any of these signals and failed to place the Tsarnaev brothers under close surveillance during the two years before they committed the Boston attack. Hopefully, the U.S. investigation into the FBI's failures will shed more light on why it dropped the ball.

Andrei Soldatov is an intelligence analyst at ?Agentura.ru and co-author of "The New Nobility: The Restoration of Russia's Security State and the Enduring Legacy of the KGB."

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.