Last week saw the toppling of the president of Abkhazia in mass protests reminiscent of those in Kiev's Maidan Square. But while the new government may resolve some tensions, the breakaway republic's ambiguous relationship to Russia may lead to yet more problems in the future.

Abkhazia, a province with about 240,000 inhabitants, broke away from Georgia with help from Russia after emerging victorious from a brutal war from 1992 to 1993. In the wake of the August 2008 war over South Ossetia, Moscow formally recognized Abkhaz sovereignty but only Nicaragua, Venezuela, Vanuatu and? Nauru followed suit. Abkhazia remains an isolated enclave dependent on Russia for contact with the outside world — and for subsidies that amount to 70 percent of its budget.

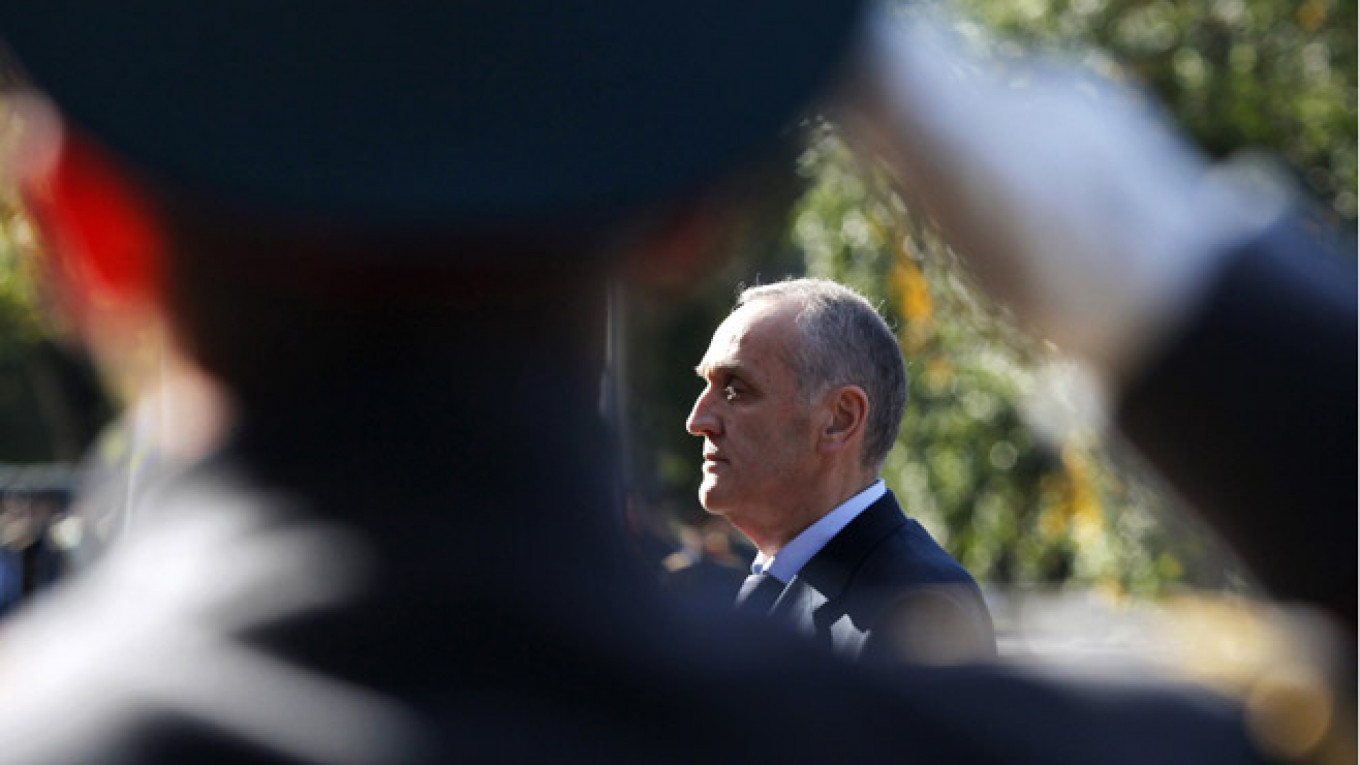

On May 27 demonstrators, variously estimated at 1,000 to 10,000 strong, stormed the presidential administration building in Sukhumi, forcing President Alexander Ankvab to flee to a nearby Russian military base. Russian presidential aide Vladislav Surkov flew in the next day for negotiations with the two sides. The parliament, which previously had supported Ankvab, then declared that he was unable to fulfill his duties and appointed its speaker Valery Bganba as interim president on May 31.

Ankvab had been elected in a more or less free election in 2011, but had grown increasingly unpopular due to corruption, unemployment and his tendency to micromanage Abkhaz affairs. The target of six failed assassination attempts, he had also reportedly angered criminal elements who still loom large in Abkhaz society. Ankvab was also criticized by opposition leader Raul Khajimba for giving passports to ethnic Georgian, mainly Mingrelian, residents in the southern Gali district, in part because of the fear that the votes of those 50,000 Georgians could sway the results of future elections.

Conspiracy theories abound, though, and the role of Moscow in these developments remains unclear. In an interview with Dozhd television on June 2, former vice speaker of the Abkhaz parliament Irina Argba blamed Russia for instigating the protests and failing to support President Ankvab.

However, no matter Abkhazia's current fate or Moscow's possible role in the protests that pushed out Ankvab, long term anxiety exists over Russia's ambiguous relationship with Abkhazia. Professor Kornely Kakachia of Tbilisi State University suggests that some Abkhaz fear that Moscow might follow up on its seizure of Crimea by annexing Abkhazia. There is also the perennial worry that at some point in the future improved relations between Russia and Georgia, a larger and more significant potential ally, might cause Moscow to abandon Abkhazia.

As a way to guarantee its independent status, Abkhazia has asked to join the new Eurasian Economic Union treaty between Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan which was signed in Astana on May 29. This is unlikely to happen, though, since neither Belarus nor Kazakhstan has recognized the sovereignty of Abkhazia, nor that of Russian-allied breakaway republics South Ossetia, Karabakh or the self-proclaimed Transdnestr republic.

Russian tourists are the backbone of Abkhazia's anemic economy, with roughly 1 million visitors per year, and oil company Rosneft is exploring for oil and gas under the Black Sea off the Abkhaz coast. The Russian government has been investing heavily in developing the transport infrastructure of South Ossetia and Abkhazia since 2010, as explained by Kommersant's Olga Allenova.

However, Russia's relationship with Abkhazia has not been all positive. According to a report last year from the auditing commission in Moscow, half of the $200 million spent in Abkhazia since 2010 had been stolen. Last year Moscow suspended payments, causing an acute financial squeeze. The Abkhaz government turned to Transdnestr, the secessionist region of Moldova, for a $6 million bridging loan.

The turmoil in Abkhazia is a small example of the way in which the recent dramatic developments in Ukraine cast a new light on Moscow's relations with all its neighboring countries and change the behavior of political actors, in ways that are hard to understand, let alone predict.

Peter Rutland is a professor of government at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, currently visiting Tbilisi.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.