More than a year into the Arab revolts, their outcomes remain highly uncertain. But some initial lessons for international politics — and for Western, particularly European, foreign policy — merit serious consideration.

Almost everyone was surprised by the revolts, although the political and socioeconomic causal factors were well known. As is often true in crises that become systemic, we knew the phenomena but failed to grasp how they affect each other — in part because politicians and analysts are unwilling to anticipate ruptures. The familiar is held to be stable even when it is known to be problematic.

Likewise, the revolts in different parts of the Arab world have made a mockery of efforts to divide states into "moderate" and "radical" anti-Western camps. This false dichotomy blinded U.S. and European leaders to many of the weaknesses that rendered even "moderate" systems unstable. A better rule of thumb would be: Beware of regimes that claim to guarantee the West's geopolitical interests.

In fact, Western states had no power over the revolts' outbreak, and they cannot determine their outcome. Even in Libya, despite NATO's decisive intervention, local actors will decide whether a democracy, another dictatorship, some kind of communitarian confederation or chaos emerges.

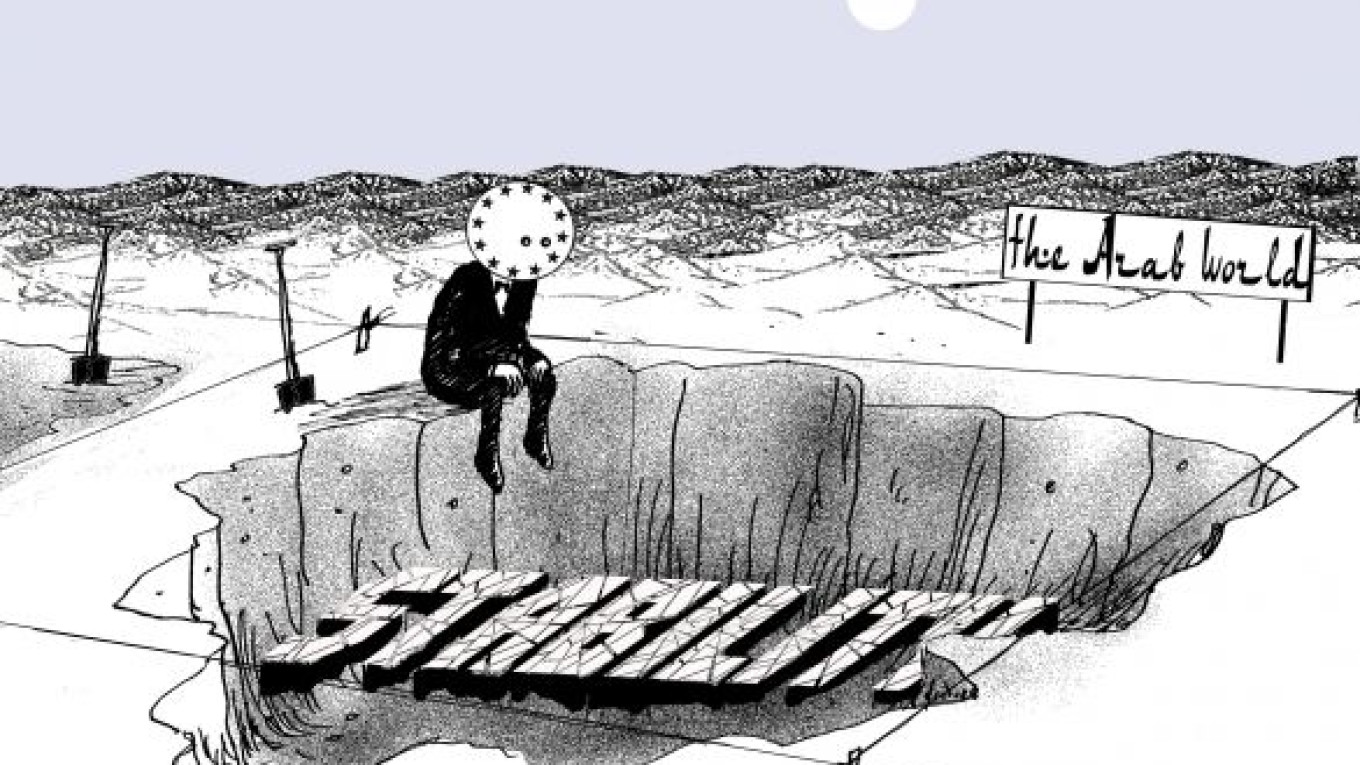

This limitation on external influence may be healthy. The legitimacy of the political and social orders that emerge from the revolutions in Tunisia, Egypt and elsewhere will largely depend on their being perceived as the outcome of authentic domestic processes. At the same time, limited influence does not relieve Europe from its responsibility toward its southern neighbors. Benign neglect will lead to unwanted reminders.

This means that the West will have to learn to deal with and even trust actors who were previously unknown. But it might help to remind ourselves that the problem in these states were the well-known elites, whom not only Europe and the United States, but also Russia and China, trusted for too long, often against their better.

Arab countries that have cast off autocratic regimes will remain unconsolidated democracies for some time. But their leaders will act with great self-confidence, often refusing the wishes of Western powers. They will point out that they, too, are accountable primarily to their own people.

Thus, the United States and Europe will not necessarily gain greater support for their preferred policies just because more states have become democratic or pluralistic. Rather, democracy itself will become more pluralistic. Like Turkey, India, Brazil or South Africa, transforming countries in the Arab world are likely to pursue a rather nationalist agenda. The United States and Europe will have to find common interests with societal actors in these countries, rather than taking for granted that such interests already exist.

Countries with a youth bulge, relatively good access to news and information, growing social inequality, widespread corruption and authoritarian governments will not remain stable forever. So autocrats in, say, Azerbaijan, Ethiopia and certainly Iran should prepare for trouble. At least some of these regimes will regard the Arab revolts as a warning and step up preventive repression, restrict the flow of information or try to divert attention from domestic politics.

Arab autocrats long relied on such tactics, often using regional conflicts for their own repressive ends. But while pointing to external enemies can no longer stop revolts and revolutions, it would be a mistake to assume that the disappearance of authoritarian regimes would lead to the swift resolution of regional conflicts. If the Bashar Assad regime in Syria is toppled, the country's new leaders would be no less adamant in calling for the return of the Golan Heights. In fact, they might pursue the claim more vigorously.

NATO's actions in Libya reopened the debate about international military interventions in the name of human rights. Indeed, the question of when the "responsibility to protect" — the legal doctrine that was applied in Libya — not only legitimizes international intervention, but also requires it. NATO states and others will have to decide whether they are prepared to act even in the absence of a United Nations Security Council mandate if there is broad regional support for intervention to protect civilians — or even to overthrow a regime.

The Arab revolts have called into question the understanding of stability that has long guided European policies toward the region. Arab and other autocrats had long been successful in presenting political stagnation as stability. Europe should continue to promote political and social stability in its neighborhood. But it needs to develop a concept of stability that allows for dynamism and change.

Above all, Europe and the West must recognize that the Arab uprisings demonstrated the vitality of the desire for democracy, individual freedom, justice and dignity. The fear of many Western observers that the rise of China would nurture a global shift toward authoritarian capitalism has clearly been exaggerated.

The activists who triggered the Arab revolts may find little attraction in many European policies, but they regard the democratic ideas that Europe cherishes as their own. Europe owes it to itself to support political transformation in the Arab world as openly as it supported the democratic transformation of Eastern Europe two decades ago.

Volker Perthes is chairman and director of Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.