President Vladimir Putin has never hidden his admiration for Yury Andropov, head of the KGB and his boss when Putin was serving in the Soviet secret police. One of Putin's first public acts after becoming prime minister in 1999 was to reinstate the memorial plaque for Andropov on the Federal Security Service building on Lubyanskaya Ploshchad. At the unveiling, Putin had only warm words for Andropov, calling him "an eminent political figure."

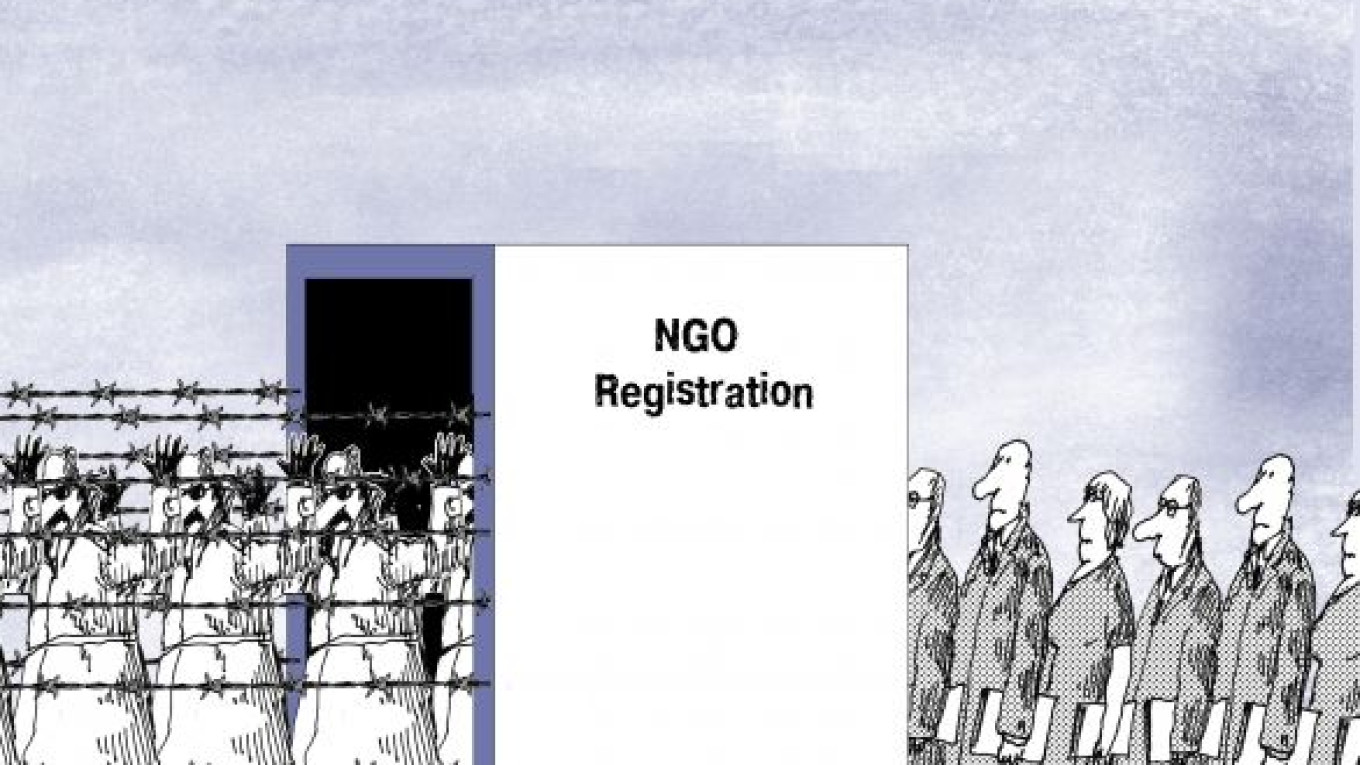

Lyudmila Alexeyeva, a veteran of the human rights movement and head of the Moscow Helsinki Group, the Andropov era in a different light. For her, it was a time when dissidents were arrested and legislation was constantly tightened. She probably felt a strong sense of deja vu as she read the new legislation passed in its first reading in the State Duma on Friday. The bill stipulates that nongovernmental organizations receiving foreign grants and conducting "political activities" must register as "foreign agents." Failure to do so will result in a wide range of punishments, from fines of 500,000 rubles ($15,220) to two years in prison.

Alexeyeva wrote on her blog on the Ekho Moskvy site, "The Moscow Helsinki Group was founded in 1976. We survived Soviet power. We worked then, and we're working now. And we'll continue to work, no matter what laws are written."

Theoretically, transparency concerning political organizations that receive foreign money is not a bad idea. Analogous legislation exists in democratic countries, most notably the Foreign Agents Registration Act in the United States. But the devil is always in the details. The new Russian bill formulates "political activities" so broadly that it includes almost everything. The legislation defines it as any activity "to influence state decision-making, change state policy or shape public opinion."

Not surprisingly, every human rights organization falls into this definition of "political."

"We don't and can't have any other function than to influence public opinion," Alexeyeva wrote. The only thing we can do is say: 'Dear citizens, if your rights are violated, we can tell you how to defend them.'"

Former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin with Alexeyeva. A statement by the Committee of Civil Initiatives, which he heads, noted that "now even appeals to build ramps for disabled people might be considered a political activity."

It appears that even the initiators of the bill recognize its absurdity, but it doesn't faze them. An anonymous official in the Kremlin Gazeta.ru that, according to his estimation, "about 1,000 organizations" would be affected by the new bill, including up to 70 percent of environmental NGOs.

The legislation has not yet been signed into effect, but there is already a booming business in denunciations of possible "foreign agents." Robert Shlegel, a Duma deputy from United Russia, believes that the Gorbachev Foundation, headed by former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, falls into this new category. "Who else but [Gorbachev] fits the description of a foreign agent? I wouldn't be at all surprised to find out he has been working for some foreign special service," he Izvestia.

Shlegel's "exposure" of Gorbachev confirms the warnings of opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, who on his LiveJournal blog: "Putin's main goal is to create an atmosphere of spy mania and hatred and to start witch hunts. Most of all, the regime wants to silence people who threaten the pillars of Putinism: falsification, corruption and police tyranny. That's why it especially hates the association Golos, which caught it stealing our votes red-handed; Amnesty International, which has exposed unjust legal rulings; and Transparency International, which has rated corruption in Putin's Russia at the level of an African country."

But some people see a positive side of the bill. Alexei Kalinov, a Moscow businessman, on his Ekho Moskvy blog, "I think that an NGO should proudly wear the title of foreign agent. And then people will see that 'foreign agents' are the only people fighting for human rights in our country. 'Foreign agents' are concerned about the environment, and 'foreign agents' are fighting corruption. Perhaps this will help change the siege mentality of our citizens."

Unfortunately, Russian history has shown that optimism is never a good tool when making predictions. It's difficult to say how many NGOs will be able to continue their work if the new legislation is put into effect. In any case, it will close the door on fundraising in Russia, since no Russian donor would dare to fund "foreign agents."

Alexeyeva wrote on her Ekho Moskvy blog: "On the day I learned that the bill had been submitted [to the Duma], I asked Mikhail Fedotov, an aide to the president, to pass on my official statement to Vladimir Putin. Under no circumstances will the Moscow Helsinki Group register as an agent of a foreign state because we are not agents."

This statement might be very risky. In his time, Andropov succeeded in dissolving the first Moscow Helsinki Group. Putin might very well enjoy doing it again out of deep respect for Andropov.

Victor Davidoff is a Moscow-based writer and journalist whose blog is

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.