When Estonia relocated a Soviet war memorial three years ago, pro-Kremlin youth activists held raucous protests in Moscow, mysterious cyber attacks hit Estonian web sites, and tensions ratcheted up to new heights between Russia and the Baltic state.

Last month, Georgia — which had already fought a brief war with Russia over its separatist region of South Ossetia — decided to take the bigger step of blowing up a similar war monument.

But the botched Dec. 19 blast of the Glory Memorial in Kutaisi, which killed two bystanders, triggered only mild criticism and a curious promise to rebuild the memorial in Moscow.

To the amazement of many, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin reacted by uttering possibly his friendliest remarks about Russian-Georgian relations in recent memory. “The relationship between our people … has a solid, centuries-old foundation, and we are linked by thousands of invisible bonds of common interest and history,” he said at a Dec. 23 meeting with Zurab Nogaideli, a former Georgian prime minister-turned-opposition politician.

What followed was the first passenger flight between Tbilisi and Moscow since the 2008 war last week, and negotiations to open the only land border crossing between the two countries in March.

The rapprochement is raising hopes that relations will return to normal — despite Moscow’s repeated promises never to work with the government of President Mikheil Saakashvili.

“I am convinced that this process will go on,” said Mikhail Khubutia, who represents tens of thousands of Georgian workers in Russia as the head of the Union of Georgians in Russia.

The signs of reconciliation are all the more remarkable because Tbilisi’s uncompromising stance against Moscow has not changed, and all official contacts remain severed.

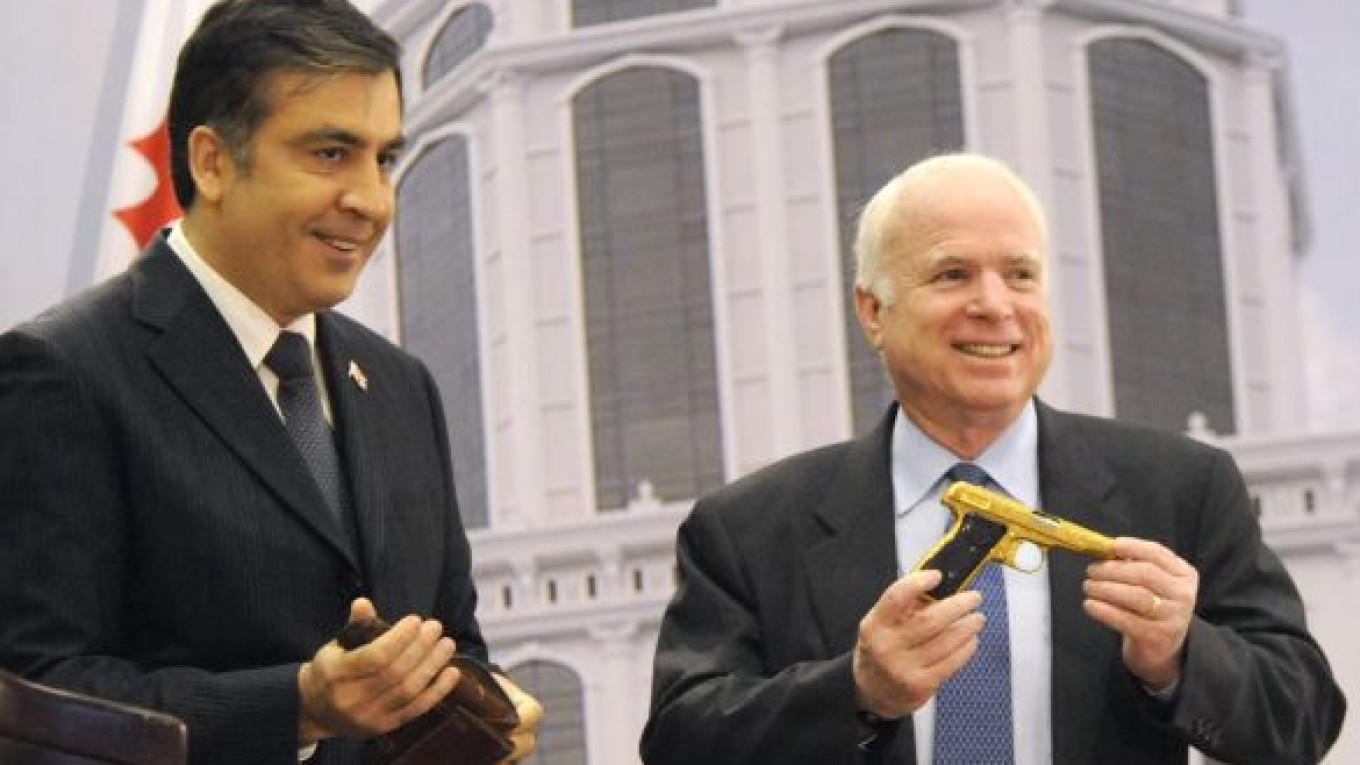

Saakashvili on Monday decorated U.S. Senator John McCain with the National Hero award, Georgia’s highest state honor. McCain, a Republican who unsuccessfully challenged Barack Obama for the U.S. presidency, is reviled in Moscow as a fervent Kremlin critic. He announced during the fighting in South Ossetia that “today, we are all Georgians.”

Saakashvili lashed out at “our enemy” — a thinly veiled reference to Russia — in a televised New Year’s address. “These days we had a chance to again see on TV screens our enemy’s mad … face. It failed to understand why Georgia could not be brought down to its knees despite many tricks and provocations,” he said, according to a transcript on the Georgian presidential web site.

President Dmitry Medvedev has brandished Saakashvili as a war criminal and Putin once reportedly promised “to hang [him] by the balls.”

Tbilisi is also stepping up efforts to counter what it calls Moscow’s propaganda war by launching a new Russian-language television channel called First Caucasus.

But representatives of Russia’s large ethnic Georgian community have high hopes that ties will further improve and that a freeze in trade, effective since 2006, might soon be over.

Khubutia said 1.5 million Georgians live in Russia, including 500,000 who send $500 million home to their families every year.

“This is very serious money,” he said.

A senior Federation Council senator cautioned, however, that Moscow would not initiate any further improvement in relations.

“Tbilisi is obviously not interested in better political relations … and as long as these people remain in power, ties cannot be reestablished,” Vasily Likhachyov, deputy chairman of the Federation Council’s International Affairs Committee, told The Moscow Times.

Likhachyov said the latest steps were just “humanitarian gestures” despite Tbilisi’s anti-Russian policies.

He said it was up to the Georgian people to vote for a new government — a common argument by Moscow officials despite signs that Georgia’s opposition has little chance of toppling Saakashvili’s government.

Sergei Markedonov, a Caucasus expert at the Institute for Political and Military Analysis, said the first charter flights and the border opening showed that a minimum level of cooperation was necessary.

“Just look at Georgia on the geopolitical map,” he said.

The opening of the Upper Lars border post, which has been closed since 2006, would also help Armenia, traditionally Moscow’s closest ally in the South Caucasus. The landlocked country has been hit hard by Russian-Georgian tensions, and it had conducted practically all its Russian trade through Georgia after Turkey and Azerbaijan imposed a blockade following a conflict over the Nagorno-Karabakh region in the early 1990s.

Turkey and Armenia agreed last October to reopen their border, but the ratification of the agreement is up in the air because of strong domestic opposition in both countries.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.