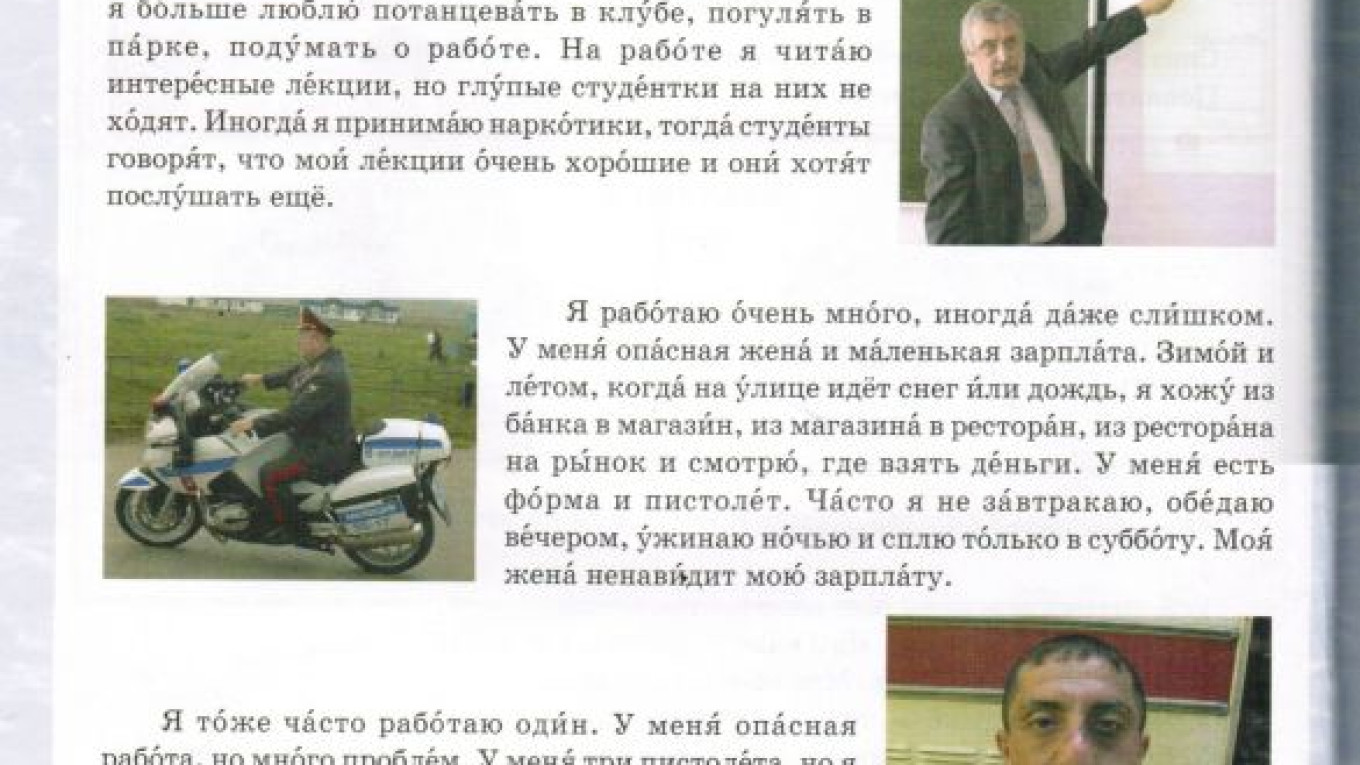

A policeman says in Russian: “I work a lot, sometimes even too much. … Winter or summer, rain or shine, I go from a bank to a store, from a store to a restaurant, from a restaurant to a market, looking for where to take money.”

What’s wrong with this passage? Is there a grammatical error or a moral dilemma? The author of “Poekhali!” (Let’s Go!), a Russian-language textbook series that has sold more than 100,000 copies around the world, maintains that passages like the one above help foreigners learn a famously complicated language.

But a United Russia lawmaker who made headlines last month with calls to raise $2.8 million to buy Hitler’s birthplace and demolish it says the textbooks are “disgracing the country” and are “worse than a manual for terrorism.”

Frants Klintsevich, deputy chairman of the State Duma’s Defense Committee, told Izvestia that the series, authored by St. Petersburg resident Stanislav Chernyshov, was tarnishing Russia’s image abroad. He has asked the prosecutor’s office to open an investigation.

“It’s outrageous. It kills the soul and creates a moronic impression of Russia. It makes foreigners think we’re all bandits, morons and drug addicts,” Klintsevich told St. Petersburg’s Channel Five.

In one edition, a professor says: “I used to love going to the university, but now I prefer to dance in a nightclub, walk in a park, think about work. At work I read interesting lectures, but stupid girl students don’t come. Sometimes I take drugs, then students say that my lectures are very good and they want to listen to more.”

The author of the series, which features beginner and intermediate editions and clearly states on the front covers that it’s “for adults,” counters that the lawmaker’s anger stems from a misinterpretation.

“The passages involving the policeman and the drug-taking professor are part of an exercise where the student is supposed to find mistakes and correct them. These phrases — about money and drugs — are mistakes,” Chernyshov said. “It’s very funny. The deputy and his assistants simply didn’t read the question properly.”

Chernyshov, who runs the Extra-Class Language Center in St. Petersburg with his wife, Alla, who co-authored the two beginner editions, is surprised that the series, whose first edition was published a decade ago, is now coming under fire.

“I believe it’s the first time in history that parliamentarians have asked for a grammar book to be investigated,” he told The Moscow Times. “I think someone was really looking for passages to prosecute and, at last, found them.”

He said other texts in the series promote moral improvement. One exercise asks students to think of ways to make the world a better place by choosing a project suitable for receiving a grant from a group of obliging businessmen. One of the suggested projects is a worldwide censorship system for ridding the Internet of “bad sites.”

The publisher, Zlatoust, said the series competes well with more sober language books, most of which were produced in the Soviet era. Foreign students asked by The Moscow Times defended the series, saying they liked its ability to spark debate.

“I think its excellent. It gives an accurate introduction to Russia,” said Simon Cahill, a 23-year-old British student. “This doesn’t mean a bad image of Russia. All the opinions and facts in it are readily available in the Russian press, which is where a lot of the material comes from, in any case.”

Not all foreign readers were as taken with the series, however. “I can understand why Russian parliament members would be upset. I personally prefer a more neutral textbook,” Alexandra Smith, a teacher at the University of Edinburgh, told The Moscow Times.

She said the series did not have a solid reputation in the context of academic learning but said some parts were useful. “I personally would be happier to use more subtle humor. Using a text on Putin, for example, is stupid on many levels and too cheap. It seems that some people in Russia feel that these sorts of things are cool and might appeal to foreigners. It’s just a commercial trick.”

Chernyshov said his aim in the series was not to express his own views but “to provoke communication — the goal of a good teacher.” One of the most-cited passages in the series is a text featuring President Vladimir Putin: “I am president. My job is very simple: I just say yes or no.”

Klintsevich’s complaint is the latest in a series of conservative interventions by United Russia deputies on cultural issues in St. Petersburg — one being the introduction of stringent anti-gay legislation in March.

Chernyshov believes that his case shows that the state is trying to widen its control over new areas of society.

“First it was oil, gas, television. Now it’s Russian as a foreign language’s turn,” he said. “I believe it is a personal campaign by Deputy Klintsevich. But I see that the state is becoming more occupied with questions on the teaching of Russian — in both a positive and a negative sense. But in any case, they want more control.”

Chernyshov paints the controversy as a struggle between a vision of education inherited from the Soviet Union and that of a democratic Russia.

“Under the Soviet Union, teaching was under very strict control, and we see that someone in power considers that today we need that sort of control again,” he said. “My books are a good sign if Russia wants to be a democracy — foreigners see that we can laugh at policemen, even at the president’s work.”

What has attracted the deputy’s anger precisely now is unclear. He is known for a charismatic style and a penchant for big public gestures. Besides his campaign to buy Hitler’s house, he has submitted a flurry of proposals in the Duma, including a suggestion that capital punishment be reintroduced for treason.

According to Klintsevich, treasonous acts warranting execution could be widened to include major wastes of state resources, such as the botched Proton-M satellite launch in August.

Chernyshov also believes that he could be the victim of a business tussle in the Russian-as-a-foreign language industry. “There’s a state program at the moment that receives money from the budget. It’s possible that a popular independent textbook bothers specific people who want to earn money by writing official textbooks. This often happens in Russia. That’s how I explain it to myself anyway.”

Repeated attempts to contact Klintsevich by phone and e-mail were unanswered. A reporter spoke with the deputy’s secretary on several days in November and December but was told he was unavailable.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.