As fallout from Russia's annexation of Crimea continues to build with economic sanctions and diplomatic spats, speculation has grown over whether the Kremlin's decision to take the Ukrainian territory was really as spontaneous as it seemed. Observers say plans to return lost Russian territories, including Crimea, have been sitting on the shelf for years.

According to former Kremlin insiders and military specialists, since the mid-2000s Russia had several plans on Ukraine, but it was the disorder that broke out in Kiev in November and the ouster of pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych on Feb. 22 that prompted Moscow to take military action in Crimea.

"The annexation of Crimea was a well-elaborated plan, it is impossible to send Main Intelligence Directorate special forces to a foreign territory without a plan," said former Kremlin spin doctor Gleb Pavlovsky.

"The fact that the operation was brilliantly implemented proves that the plan was created long ago and was kept at the General Staff's office for years," he said.

Apparently, Kremlin maneuvers to keep Ukraine in Russia's orbit after unrest first erupted in Kiev were noticed even by Western powers.

The Wall Street Journal reported earlier this week that U.S. intelligence told the White House that Putin had an interest in Crimea becoming part of Russia as early as December, with U.S. officials suspecting that Russia might have been moving highly trained units into Crimea in small quantities over the last few months.

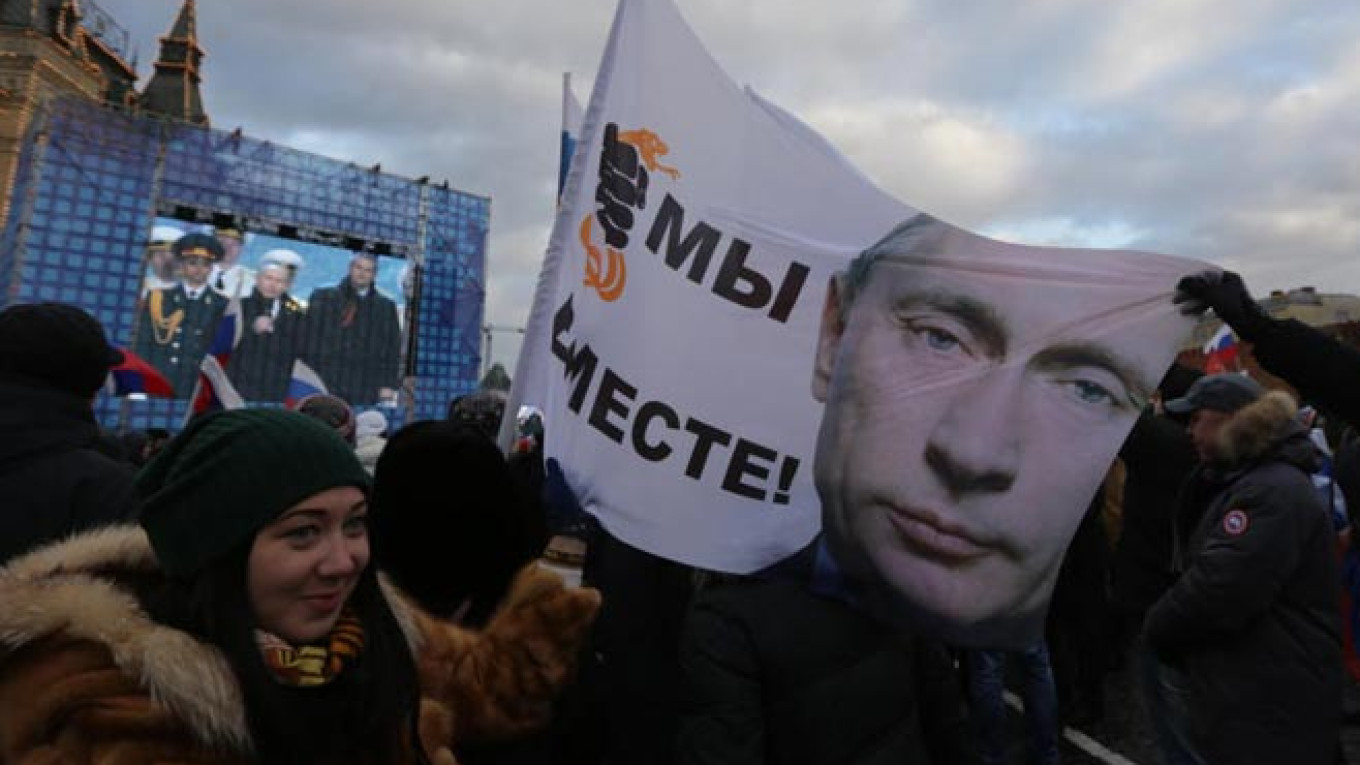

President Vladimir Putin's interest in lands that formerly belonged to Russia is no secret. Once calling the Soviet Union's collapse the "greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century," he has said on numerous occasions that he wanted to restore Russia's glory as a world superpower.

"Putin wants to go down in history as a person who brought Russia's lost territories back. He has had this idea for a long time," said Gennady Gudkov, former deputy head of the State Duma's Security Committee and a colonel of the Federal Security Service in reserve.

In one clear sign that Putin considers Ukraine crucial to Russia's own interests, Russia and Ukraine signed a deal in 2010 that saw Russia lower gas rates for Ukraine in exchange for Russia being allowed to keep its Black Sea Fleet in Crimea until 2042. The move seemed aimed at reassuring the Kremlin that Ukraine would remain in Russia's sphere of influence and not move closer to Europe.

But Ukraine's plan to sign an association agreement with the European Union in 2013 was an unexpected development for Russia, as were the protests that flared up after Yanukovych's backtracking on that agreement.

The protests in Kiev forced Russia to change its strategy in Ukraine very quickly, observers say, with the Kremlin pushing Yanukovych to use tough measures against the Maidan demonstrators in a bid to quell the discontent.

As early as December, Putin said he was concerned about Russians living abroad. But he also said at that time that Russia would not use military force in Crimea — apparently refuting analysts' predictions from last fall that Moscow could take measures to protect Russian interests in Crimea if the situation worsened.

"The Kremlin always has several plans on various issues that may not be in use for years but then when some trigger appears, Putin asks to put one of the plans into action. So the Crimea operation may have been prepared long ago, but the decision on it was made very quickly," said Andrei Soldatov, a prominent security services expert who runs the think tank Agentura.ru.

In September, when Russia and Ukraine were at odds over gas and trade issues, Putin appointed his advisor Vladislav Surkov — who worked in Ukraine during the Orange Revolution in 2004 and is believed to have promoted Yanukovych at that time — as a curator of relations with Ukraine.

Surkov is credited with playing a key role in the development of Putin's political system, with observers saying after his appointment that he was needed to lobby Russia's position in Ukraine and inspire pro-Russian forces to oppose growing pro-Western sentiments in Ukraine.

By September, tensions between Russia and Ukraine had heated up significantly, with Ukraine asking Russia to reduce gas prices and Russia banning some Ukrainian goods from the Russian market and insisting that Ukraine become part of the Moscow-led Customs Union.

Surkov was supposed to resolve economic and trade disagreements between the two states during this time. And in the run-up to Yanukovych's ouster in February, several trips made by Surkov to Ukraine seem to indicate that Russia was pulling out all the stops to keep a strong foothold in Ukraine.

After first making visits to Kiev, Surkov went to Crimea in mid-February to meet with Crimean and Sevastopol authorities and to discuss with them the construction of a bridge connecting Russia and Crimea. The talks were followed by a meeting in Moscow on Feb. 20 between head of the Crimean parliament Vladimir Konstantinov and Sergei Naryshkin, the speaker of the State Duma.

Pavel Salin, director of the Center for Political Studies at the Financial University of the Russian Government, said that while Surkov's role in Crimea's annexation was not crucial, it was likely meant to establish dialogue with Crimean Tatars.

Most observers agreed that the final decision to annex Crimea was made in late January, when it became clear that Yanukovych would not be able to hold on to power. Military preparations and implementation of the plan required no more than a few days because of the close proximity of the Ukrainian border and the fact that there were already troops specially trained for such an operation,? military experts say.

In December, a lawmaker from Sevastopol, Sergei Smolyaninov, asked Putin to bring Russian troops into Ukraine to fight Maidan protesters and protect Russians in Crimea. In January, such appeals by lawmakers significantly intensified.

On Feb. 4, Crimean lawmakers proposed asking Russia to guarantee the inviolability of Crimea's status of autonomy amid the political crisis in Ukraine, saying Russia could be the only protector of Crimea, since most of its residents were Russians. But the lawmakers said at that time that the question was about political rather than military help.

Kyiv Post, referring to a document allegedly produced by Russia's National Security Council, reported last week that Yanukovych was designated to play a major role in Russia's plan. According to the report, he was supposed to sign a document on Feb. 7 asking Russia to send troops to Ukraine to protect its constitutional order. The report also said that other Ukrainian territories, including Kiev, were supposed to be under Moscow's control in order to defend Russia's interests in the region.

Ukrainian media have alleged that the pro-Russian forces in Crimea and appeals to Putin were a result of Surkov's work in Ukraine, who they said was sent there not to preserve Yanukovych's power but to weaken Ukraine and take advantage of the situation.

Observers paint a different picture, however, saying the Kremlin in fact did want to keep Yanukovych in power, and only began to develop the annexation scenario when it became obvious that Yanukovych was a lost cause. ?

"Putin is very concerned about his image as a person who is always right, so he decided to enter the game and show the world that the main victory belongs to Russia," said Ilya Ponomaryov, a State Duma deputy who was the only one to vote against the agreement on Crimea's annexation last week.

Ponomaryov said the decision to annex Crimea was unilateral and even the Presidential Administration was excluded from making it.

Former spin doctor Pavlovsky said he had always expected the Kremlin's grip to spread outside Russia.

"But I could not have predicted that the Kremlin would make such a wrong move strategically, which was a point of no return because it violated a number of requirements and strategies, created new enemies and frightened friends," he said.

Contact the author at e.kravtsova@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.