The image of Khrushchev banging his shoe on his desk during a General Assembly session in October 1960 is so vivid that it remains in the popular consciousness though no known photograph of the outburst exists.

The UN stage that President Vladimir Putin will take this week has changed radically over the organization's 60-year history. The world body has grown from 51 members to 191, and its structure and mission continue to evolve. But one constant over the decades has been the centrality of the Russian role in the organization -- and the ability of Russian leaders to cause a stir.

The Soviet Union's contentious role began before the UN had come into being. Negotiations to build an international body that would "save succeeding generations from the scourge of war," as the UN charter states, hit a roadblock in 1944. The Soviet Union insisted that each of its 15 constituent republics be granted member status -- and hence a vote in the General Assembly. The United States responded by proposing that each of its then-48 states be given a vote as well.

In the end, only Ukraine and Belarus received separate member status. It was an early sign the organization would rarely work from a consensus.

Thomas Pickering, the U.S. Ambassador to the UN from 1989 to 1992, said that another defining moment in Soviet-UN relations came in 1950. Along with the United States, France, Britain and the Republic of China, the Soviet Union held a permanent seat on the UN Security Council that gave it veto power it rarely hesitated to use. Of the 78 Security Council vetoes in the first 10 years of UN history, 75 came from the Soviet Union.

But in 1950, the Soviet Union was boycotting the UN over its refusal to recognize communist China, which had forced the Republic of China's government to flee to Taiwan.

"The other Security Council members took advantage of the boycott to pass the equivalent of a use of force resolution over Korea," Pickering said by telephone from Washington on Tuesday.

The resolution -- which members knew would have been vetoed by the Soviet Union -- led to the expulsion of communist troops from South Korea by U.S.-led forces.

"It was the very antithesis of what would happen in 1990, when we had agreement with the Soviet Union on a use of force resolution in the Persian Gulf," Pickering said. "That was an evolution of events that proved the Cold War was dead."

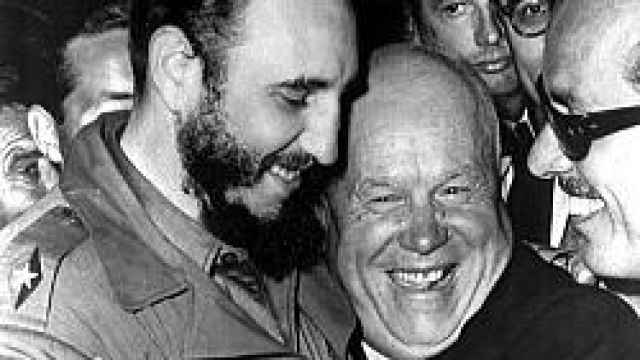

Marty Lederhandler / AP Nikita Khrushchev and Fidel Castro embracing at the United Nations in 1960. | |

The assembly opened on Sept. 20 with New York astir over the presence of Fidel Castro, who had seized power in Cuba the previous year. Krushchev met Castro like a long-lost brother.

During the UN session that followed, the Soviet premier called for the resignation of Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold, accused the United States of elevating "violations of international law into a principle of deliberate state policy" and interrupted speeches by other world leaders by shouting and pounding his fists.

The shoe hit the desk on Oct. 11 when Philippines Ambassador Lorenzo Sumulong suggested that Krushchev's complaints about Western imperialism were at odds with the Soviet Union's own imperial moves in Eastern Europe. Krushchev erupted with rage, calling the ambassador "a lackey and an imperialist stooge." He punctuated the invective with his right shoe.

A more startling confrontation took place during an emergency UN session two years later. On Oct. 25, 1962, U.S. Ambassador to the UN Adlai Stevenson demanded that Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin admit or deny the presence of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. When Zorin refused to answer, Stevenson displayed U.S. reconnaissance photos of missile sites to a stunned General Assembly.

Pickering recalled the years when the Soviet presence in the UN had a very different character. On Dec. 7, 1988, Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev made a speech to the General Assembly announcing significant cutbacks in Soviet troops from the German Democratic Republic, Czechoslovakia and Hungary.

"There was a sense of guarded optimism," Pickering said. "We on the other side were always wondering if he was serious about making major structural changes. By 1989, we had become convinced that he was."

Pickering said the unanimous Security Council decision in 1990 to repel the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait represented "a fundamental change" in Soviet-UN relations.

"We saw the emergence over a short period of time of what can be called a general meeting of the minds," he said. "I felt I was there at an extremely interesting time because I saw the change from Cold War politics to the near-epitome of cooperation."

Win Mcnamee / Reuters Boris Yeltsin greeting Fidel Castro at the UN in 1995, when the UN turned 50. | |

"We went home for Christmas vacation with the Soviet Union and came back with the Russian Federation. There was a lot of drama around Yeltsin's visit," said Pickering, who is now senior vice president for international relations at Boeing.

The UN's 50th anniversary session in October 1995 brought Yeltsin back to New York for more drama. In the General Assembly Hall, he charged that the NATO peacekeeping mission to Bosnia represented "an obvious and clear-cut violation of the foundations" of the UN. His fond embraces with Castro revived memories of Krushchev in the American media.

During a mini-summit with U.S. President Bill Clinton later in his visit, Yeltsin responded to media predictions that the meeting would be a disaster by saying, "Now, for the first time, I can tell you that you're a disaster!"

Clinton responded by laughing himself to tears.

Even as the UN focuses on topics such as HIV/AIDS and world poverty during its 60th anniversary session this week, Pickering said the organization's future effectiveness would depend in part on the ability of the old Cold War foes to work in tandem.

"I think we still need to build cooperation between the U.S. and Russia in the United Nations," Pickering said. "My hope is that when President Bush meets President Putin, that topic will be one they face together."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.