KUPOL MINE — Every winter, an ice road is laid across 400 kilometers of tundra to carry supplies to one of the world’s most isolated gold mines.

There is no other way for heavy machinery to reach Kupol, the $700 million Arctic mine behind a resurgence in Russian gold production after five straight years of decline.

“It’s one of the harshest climates I’ve worked in, and I’ve worked in the Atacama Desert in Chile and at 15,000 feet (4,500 meters) in Indonesia,” said Patrick Dougherty, general manager at Kupol.

“But I don’t get to pick where the gold is.”

Only South Africa holds more gold than Russia, but Moscow’s fragmented industry has struggled to access vast reserves in its inhospitable Far East. The region was first mined in the 1930s by prisoners of the gulag set up by Stalin.

Falling energy prices and reduced demand have cut income from natural resources to about 8 percent of the country’s gross domestic product in the first quarter of 2009, from nearly 11 percent a year ago.

Gold, on the other hand, has been helped by recession.

Its safe-haven appeal has shielded it from a demand slump that shredded other commodity prices, lifting it by 10 percent this year to keep it within striking distance of a record price of almost $1,031 an ounce set in March 2008.

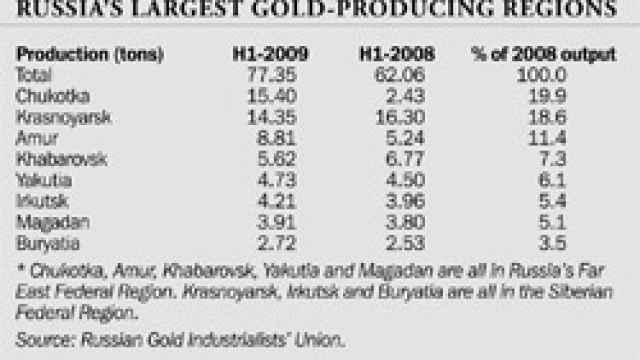

Chukotka, a region revived in the last eight years by $2.5 billion of investments from Roman Abramovich, produced a fifth of the country’s gold in the first half of this year. Gold is the region’s passport to growth after Abramovich quit as governor last July.

Russia ranked fifth among the world’s gold miners last year, between Australia and Peru, with an 8 percent share of output. Production rose 13 percent in 2008, the first increase in six years, and jumped another 25 percent in the first half of 2009.

“This was solely because of the commissioning of Kupol,” said Olga Okuneva, mining analyst at Deutsche Bank. “If other large projects in the Far East start producing gold, this will be a major growth driver for the gold industry.”

Kupol — meaning dome in Russian — is named after a rounded outcrop of rock that juts skyward from the tundra in central Chukotka, over 200 kilometers from the nearest settlement.

The mine took five years to build. It is the source of tax revenues in Chukotka, a land twice the size of Germany, where reindeer outnumber people four to one.

“With a deposit as large as Kupol, mining’s contribution to the regional economy is expected almost to double to 37 percent this year,” said Roman Kopin, the 35-year-old who took over as governor when Abramovich resigned.

|

Kinross Gold, the Canadian miner that owns 75 percent of Kupol, is unusual among foreign investors for holding a majority share in a major Russian mineral deposit. The government of Chukotka owns the other 25 percent.

Untangling the red tape that stifles some foreign investors in other parts of Russia was one of the main achievements of Abramovich’s more than seven years as governor, Kopin said.

“The investment climate here, perhaps, is a little bit different, because we understand that it’s very difficult to work in Chukotka,” he added.

Kinross has been the top-performing gold stock on the New York Stock Exchange for the last three years, when the company’s value rose more than 160 percent. Kupol will supply about a third of its total output this year.

About 1,400 jobs are related directly to Kupol, and Chukotka’s population totals about 50,000. Miners and catering staff spend four weeks on-site and four weeks off, earning an average monthly wage of 50,000 rubles (about $1,530), 25 percent above the regional average.

“We have equipment that works here,” said Alexander Puzovets, 48, a drill rig operator who works 10-hour shifts at the pit face. “I’ve been in mines where we’ve used hammers.”

The mine’s in-house electricity plant could generate enough to power the regional capital, Anadyr.

In winter, miners walk the specially built Arctic Corridor — an enclosed, 900-meter tunnel from camp to mine — to avoid temperatures that drop more than 50 degrees Celsius below zero.

About 60 percent of Kupol’s gold is mined underground. Zurab Samteladze, a 55-year-old Georgian more than 7,000 kilometers from home, hauls 45-ton rock loads to the surface in a Caterpillar truck.

In deeper parts of the mine, skilled operators maneuver drill rigs by remote control. This avoids the need for miners to work long hours beneath areas vulnerable to rock falls.

“With all the video games they play, the younger generation has a better chance of operating these units,” said Dougherty.

Alcohol is banned. Miners pass their time playing pool, in the gym or watching television. Popcorn is a popular snack, while 8 tons of reindeer meat was served up last year.

“I play guitar — they have a music room. I like basketball — they have a sports hall,” said Andrei Aksanov, 34, a mechanic in the truck shop.

Like 80 percent of the miners at Kupol, Aksanov comes from Magadan, located 1,500 kilometers to the southwest.

Magadan is where mining began in the Far East. Stalin, needing bodies to unearth newfound gold reserves, sent hundreds of thousands of prisoners to slave in the region’s labor camps over two decades from the early 1930s.

From such grisly beginnings, Magadan has developed into the hub of gold processing in the Far East. Kupol flies its dore — bullion bars to be processed into almost pure metal — to be refined at the Kolyma Refinery to the north of the city.

Vladislav Feoktistov, the refinery’s 71-year-old director, raised a glass of vodka to visiting officials from Kinross Gold. Supplies from Kupol will guarantee the plant’s biggest turnover in its 11-year history, he said.

“This is a business that’s only as good as its suppliers,” he said. From here, 15-kilogram gold bars worth more than $450,000 each at current prices are delivered to the country’s banks.

There should be more to come. Polyus Gold, owned by billionaires Mikhail Prokhorov and Suleiman Kerimov, plans to launch Natalka, the world’s third-largest gold deposit, in 2013.

Annual production of between 25 tons and 30 tons will put Natalka on the same scale as Kupol. Beyond 2017, Polyus plans to raise output to more than 40 tons a year.

“It’s a deposit with reserves of more than 1,000 tons that will create jobs, infrastructure and become a major center for the Magadan region,” said German Pikhoya, Polyus Gold’s deputy chief executive for strategy and corporate development.

If Chukotka is to retain its leading position, it must do more. Current reserves at Kupol will last only until 2016. To extend the mine’s life beyond this date, more reserves must be found, mapped and registered with authorities. Kinross and others are already exploring.

“Chukotka is definitely a key gold-producing region, particularly in the long term,” said Vitaly Nesis, chief executive of Polymetal. His company plans to launch the Mayskoye gold deposit in Chukotka by 2011.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.