It is hard to imagine Rüdiger von Fritsch, a distinguished ambassador in his seventh decade, ever having been a hitchhiker. But that is exactly where his path to diplomacy started — on a year-long journey around the globe taken straight after graduating from high school.

After traveling through Greece, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, the future historian and ambassador to Poland and Russia went all the way down to Australia. "There I earned some money, spent some time in New Zealand and worked my way back to Europe on a cargo ship," von Fritsch recalls.

Many things amazed him during the journey, but the most interesting part was trying to "understand how people saw his country" and "explaining to them why we do things the way we do." Those two things formed the core of his later diplomatic work, he says.

One other vivid memory from his adolescence was becoming acquainted with a then-obscure book called "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich," a novel by the renowned Soviet dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn. "I was given it when I was 15 or so, and I was deeply impressed," he says. "It was the first political book that I read. Ever since, the oppression of freedom and the division of East and West have been very much on my mind."

Decades later, von Fritsch has found himself representing Germany in Russia.

"In the past 25 years Russia and Germany have built a very solid, good relationship. We work together in many fields ?€” economy, trade, culture, science ?€” and we need to continue building as many bridges as possible with each other," Rüdiger von Fritsch says.

The Smuggler

Von Fritsch started his career in the socialist world, with an initial diplomatic posting in Warsaw, Poland in 1986. "I was deeply interested in socialist countries and actually asked to be sent to one of them," he says.

The fascination with the world behind the Iron Curtain was fueled by his close connections to East Germany. Part of his family lived there, he spent a vacation there once and felt able to compare life in a socialist country to life in the West.

Life in East Germany certainly wasn't easy. Restrictions on travel, expression and money took a great toll on East German citizens, including the ambassador's cousin. "My cousin wanted to study law, but he refused to join the ruling party's youth movement, which meant that he couldn't study law," von Fritsch says. When the future ambassador was just 19, he received a letter that his cousin had somehow managed to smuggle out. The message of the letter was simple enough: "Get me out of here."

That is how the young von Fritsch and his brother became involved in a secret operation of audacious proportions. After nine months of preparation and plotting, a plan that would allow their relatives to reunite with the family in the West was ready.

Then, it was impossible to cross the border between the two Germanies directly. The demarcation line splitting East from West was fortified with mine fields, trap wires and automatic shooting machines that killed anyone who tried to cross illegally. So the brothers came up with a cover story that would allow them to bring their cousin to the West via Bulgaria and Turkey. "We pretended that our cousin and his friends were hitchhikers from West Germany, traveling to Bulgaria and Turkey. The plan was to meet them in Bulgaria with fake West German passports and accompany them to West Germany through Turkey," von Fritsch says.

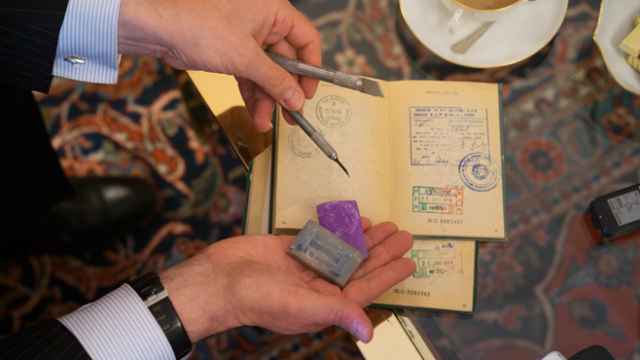

With his own hands, the future diplomat crafted all the necessary visa and transit stamps, using various rubber stamps and ink. The first attempt ended in failure, when a change of the color of the visa stamp ink meant they couldn't use the forged passports they had brought with them. "However, that failure saved us: We learned then that border guards used fluorescent ink in their stamps," he says. "So we went back and got new passports, new rubber stamps and started looking for fluorescent ink."

On the second attempt, the operation was successful and his cousin and friends safely made it to West Germany. The family resolved never to talk about this dangerous adventure. "Even though we had the best intentions, my brother and I violated West German laws. We forged passports," von Fritsch says. "Already back then, I couldn't rule out that I might want to enter public service."

When he went public about the story in 2009, his colleagues reacted differently. "Our former head of personnel told me that he wouldn't have hired me had he known about it," von Fritsch says with a laugh. "While the then-Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher said that he would have promoted me to working in his office immediately ?€” because they always need creative people there."

The ambassador's interest in the socialist world never faded. Indeed, he began to work ever more to prevent the tyranny he had seen in socialist countries. "It angered me and fascinated me at the same time. Yes, the repressions angered me. Yet I was also amazed by the fact that this Leninist machine managed to constantly suppress people without them seemingly being able to change anything," von Fritsch says.

"Thankfully, they were proven wrong there: You can't oppress freedom forever."

When just 19 years old, Rüdiger von Fritsch and his brother crafted fake visas and transport stamps to allow his cousin and friends to reunite with family in West Germany.

The Diplomat

Von Fritsch came to Russia following four years as ambassador to Poland, and three years in the German Intelligence Service, where he worked as a diplomatic advisor. It was March 2014 ?€” right after the Crimea annexation and on the eve of the military conflict sparking in eastern Ukraine. It was a difficult time, he admits, for the German political mind-set. "Germany has learned from its own history. It understands how arbitrary politics can lead to terrible suffering and injustice in a large part of Europe," von Fritsch says. "After World War II, we made a decision to never resort to arbitrary politics again ?€” only rules, regulations, treaties, and trying to stick to them to the greatest extent possible. So for us, Crimea was a very severe breach."

Several aspects of local political reality remain of "deep concern" to the ambassador. The media ?€” "not as free and competitive as one would wish them to be" ?€” the crackdown on political opposition, the various restrictions that don't allow people to express their opinion freely, and the dominating role of state propaganda that encourages people to attack those who disagree are all troubling features of the new Russia. Speaking out on this isn't interfering in internal affairs, says the ambassador: "It's simply referring to the pledges we made to each other in the Helsinki agreements."

Von Fritsch recently found himself in the middle of a storm during an event organized by the famous Russian human rights NGO ?€” Memorial. "When I arrived, there was a group of people who were throwing paint and eggs at participants. They seemed to understand that I was the ambassador, because I was only yelled at and insulted," von Fritsch says. "These people were not necessarily deliberately organized by someone, but they clearly seemed to feel encouraged to behave this way."

Despite the tension, von Fritsch sees his role as ambassador to find as many fields of cooperation as possible and keep this cooperation alive. "In the past 25 years Russia and Germany have built a very solid, good relationship. We work together in many fields ?€” economy, trade, culture, science ?€” and we need to continue building as many bridges as possible with each other," von Fritsch says.

The Historian

In the meantime, the ambassador and his family enjoy life in Moscow, which is an "exciting and wonderful place" for von Fritsch and his wife, both historians by education. They live in a mansion in the very heart of Moscow that has been the residence of German ambassadors for 60 years, and they enjoy its proximity to historical sites.

"We like to stroll around the neighborhood and discover the historical parts of the Arbat. So many of the great poets lived there ?€” be it Alexander Pushkin or Mikhail Lermontov, Anton Chekhov or Marina Tsvetaeva, and they all left traces," von Fritsch says. "And many had very close ties with Germany. Tsvetaeva was friends with German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, for example. So for us it's very interesting to explore cultural and historical connections between our two countries."

In his youth the ambassador started to learn Russian owing to family roots. "My relatives ?€” those from my mother's family ?€” spoke wonderful Russian, and when I was a school kid, I decided to learn it in my free time," he says.

"My teacher, Miss Gendel, had emigrated from Russia after the 1917 October revolution. She was a descendant of German composer Handel's family, who at some point had moved to the Russian Empire," he says.

"You see how everything is connected?"

Contact the author at d.litvinova@imedia.ru. Follow the author on Twitter at @dashalitvinovv

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.