Until last month, Bukovsky, 65, did not have a Russian passport. He blames President Vladimir Putin for the death of his friend Alexander Litvinenko, and he assails his adopted country, Britain, for its "weak" response to the Andrei Lugovoi affair.

Bukovsky is not just opposition-minded, he is "beyond opposition," in the dismissive words of one political analyst -- a label that describes both his appeal and the weakness that will ensure he stands little chance of becoming president if he manages to get on the ballot.

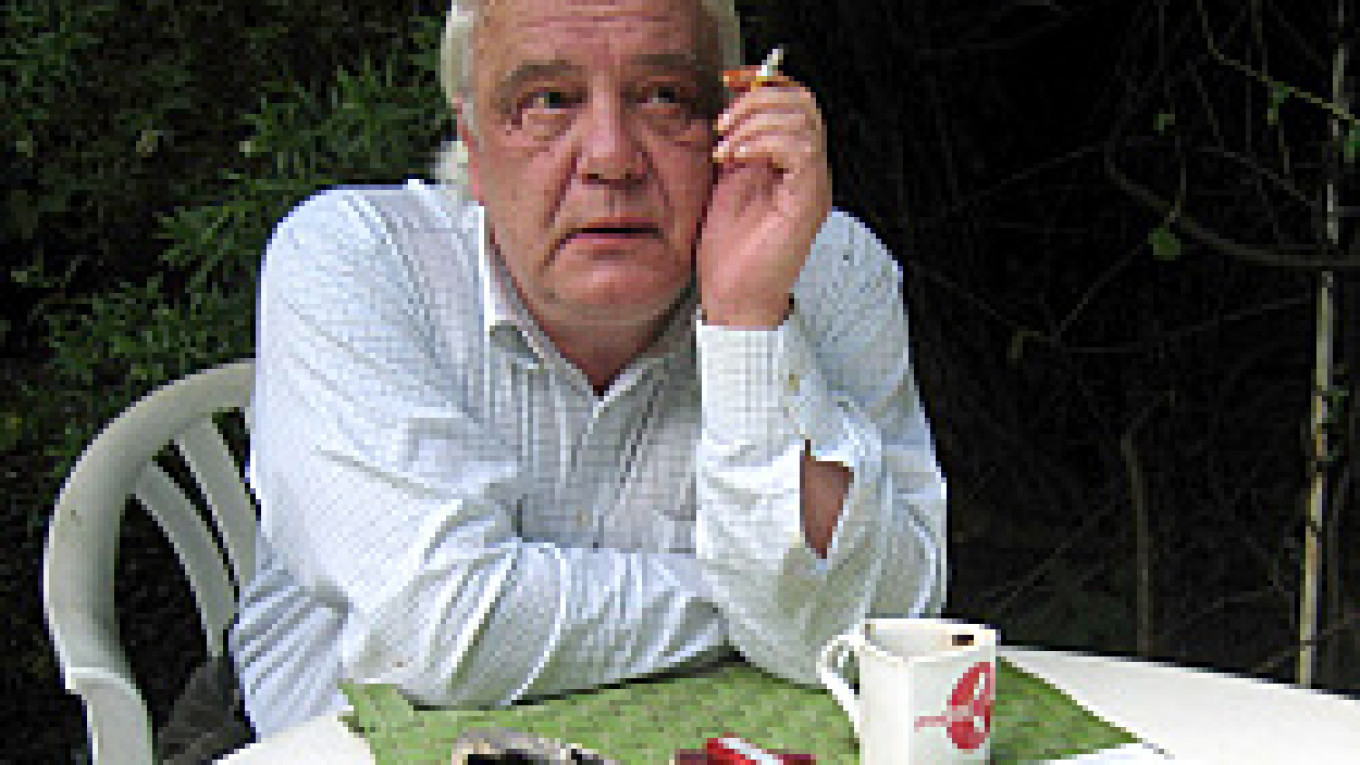

"They have dismantled everything in Russia that remotely resembled democracy," said Bukovsky, sitting in a plastic chair in his back garden, smoking one cigarette after the other. "People are now in jail. It is all returning. It is the return of the Soviet system. ... There are some frightening similarities."

Bukovsky spent more than 12 years in camps and psychiatric hospitals from the age of 16, when he joined an underground organization at school, until he was expelled from the Soviet Union at the age of 33. He became one of the era's most famous dissidents, meeting presidents and prime ministers as he campaigned against the Soviet system.

In May, he declared his intention to run for president in the March election. His candidacy was put forward by a group of prominent liberal activists, including satirist Viktor Shenderovich, political analyst Andrei Piontkovsky and journalist Vladimir Kara-Murza.

"I would like it if a person like Bukovsky could be our president, but it will never happen," said veteran human rights campaigner Lyudmila Alexeyeva, who has known Bukovsky for more than 30 years. "Nobody will allow him to register."

Alexeyeva called Bukovsky brave and intelligent, but with state control over the media, she added, only the older generation remembers him.

Bukovsky plans to return to Russia in October for the first time in more than a decade to bolster the opposition. "The opposition is completely destroyed, so the idea is to just help the opposition to recreate themselves, to reinvent themselves," he said on a recent afternoon.

He had just heard that, to his surprise, he was being issued a new Russian passport. His previous one had expired, and he was refused a visa when he last tried to visit on his British passport.

He has been back to Russia a handful of times since the Soviet collapse. The first time was in 1992, when President Boris Yeltsin gave him a Russian passport and even considered him as a vice presidential candidate.

The next year, he tried to renounce his Russian citizenship to protest Yeltsin's introduction of a new constitution but could not find a way to do it, he recalled with a chuckle.

"I don't think there is anyone in Russia today with a more clear opposition attitude to the current system than me," he said. "I give a quite a polar opposition to the current powers."

He is dismissive of opposition leaders such as Mikhail Kasyanov and Viktor Gerashchenko. "None of these people really can be opposition leaders," he said. "I mean, they have already been in power, and people know really what to expect from them."

Of President Vladimir Putin, he said: "I was worried as soon as he was appointed as a successor. At that time, the world was rather optimistic, upbeat, saying he's young and energetic, as if it is good to have a young and energetic bastard."

Bukovsky has never been known for hiding his feelings. Under the Soviet regime, he was branded a "psychopath" by state psychiatrists for his opposition activities. It was through Bukovsky that the West first learned about punitive psychiatry after his accounts were smuggled out of the Soviet Union in the 1970s.

In 1976, he was taken by force from the Soviet Union, flown out by special forces to Zurich, and swapped for jailed Chilean communist Luis Corvalan. The exchange sparked a chastushki, or dirty limerick: "They swapped a hooligan for Luis Corvalan. Where can you find such a bastard to swap for Brezhnev?"

Currently, Bukovsky, a neuroscientist with degrees from Cambridge and Stanford, lives on a quiet street of unexceptional two-story houses in north Cambridge. His front and back gardens are wild and overgrown, and he said with a smile that the only people who can see anything in his garden are the folks at Google.

bukovsky2008.org Bukovsky with U.S. President Jimmy Carter in 1977, a year after his expulsion. | |

Always the dissident, Bukovsky has provided inspiration for others disenchanted with Russia, including Litvinenko, the former FSB officer who died of radioactive poisoning in London in November.

"Sasha was a good friend. He was almost like a younger brother to me. He used to come and ask me for advice and call me 15 times a day," Bukovsky said.

Bukovsky was fundamental in bringing Litvinenko to Britain in the first place. He was contacted by Alex Goldfarb, Boris Berezovsky's aide with Litvinenko in Turkey, after he was refused asylum by the U.S. Embassy. Bukovsky advised Goldfarb to crash land in Britain. The term "crash land," Bukovsky explained, originated during the Afghan war when a Soviet soldier wanting to defect would schedule a stopover flight in Britain, "grab the first policeman at Heathrow and say, 'I want political asylum.'"

That is exactly what Litvinenko did in 2000 -- despite reluctance from then-Prime Minister Tony Blair, who didn't want to provoke a scandal with Putin, Bukovsky said.

"When he came [to Britain], Blair didn't believe that it was done by us," he said, citing sources he refused to disclose. "He was screaming at MI6, 'Why did you bring him? I told you not to bring him. ... I have enough problems with Putin already.' ... And they would try to explain, 'It is not us.'"

Blair ordered MI6 not to interview Litvinenko, he said.

Britain's Foreign Office declined to comment on Bukovsky's account.

Bukovsky blames the Kremlin for Litvinenko's death and is dismissive of Britain's reaction. "If that had happened in the 19th century, the Royal Navy would be sailing to St. Petersburg. It's an act of aggression, an act of radioactive aggression against a NATO country," he said.

Britain has charged former security service officer Andrei Lugovoi in the murder. Russia has refused to extradite him, prompting Britain to expel four Russian diplomats.

"It's too weak," Bukovsky said of the expulsions. Instead, he said, Britain should have demanded that Russia ditch a law allowing its special forces to kill perceived security threats abroad. If Russia had refused, it should have been thrown out of the Group of Eight, he said.

The Kremlin denies involvement in Litvinenko's death.

| ||||

Bukovsky faces some major obstacles before he even gets on the ballot. Candidates are not allowed to have dual citizenship, and they need to live in Russia for 10 years before the election.

Bukovsky has consulted with lawyers about the two issues. He said he had found a legal loophole that he believed could let him run with dual citizenship. As for 10-year residency, "Lawyers say it is not clear what 'constant prozhivaniye' means," he said, switching to Russian for the word "residency."

General Alexander Lebed, who ran for president in 1996, had not lived in Russia for 10 years; he had served for years as a commanding officer in Moldova. Technically, Bukovsky said, neither Yeltsin nor Putin lived in Russia for 10 years before their elections because Russia did not exist as a country before December 1991.

No matter how many arguments Bukovsky puts forward, he said he knew that the only way he would get on the ballot was with the Kremlin's blessing.

"I would imagine the authorities right now don't take [the bid] seriously. This is why I got the passport so easily, and they seem to realize that it is in their hands whether or not to register [my candidacy]. They feel they are comfortable, so they are not afraid," he said.

He says that if he does get on the ballot, he will have to be ready for anything. "Elections are very dirty. ... The first thing they will do is portray me as an agent of the MI6," he said with a deep laugh.

Bukovsky recently was described as a "psychopath" in a Daily Telegraph report, which cited an unidentified official at the Serbsky Institute, the heart of the punitive psychiatry program in the Soviet Union.

The institute later denied that any of its officials had made the statement. The Daily Telegraph stands by its story, said Moscow bureau chief Adrian Blomfeld.

Bukovsky said he would fashion his electoral platform after he arrived in Russia next month. Some things are clear, though. He is a keen federalist and abhors the state capitalism that has expanded under Putin. "Huge companies like Gazprom are really an abomination. I cannot imagine how much money they waste," he said.

State media have all but ignored Bukovsky, and his candidacy has received little coverage in mainstream newspapers. For now, Bukovsky is letting his campaign web site, Bukovsky2008.org, speak for his bid.

"Bukovsky is one of the bravest and decent people in Russia," former Deputy Prime Minister Boris Nemtsov said on the web site. "I am proud that I know this man."

Poet Lev Rubinstein quotes from a 1968 barricade poster when talking about Bukovsky on the web site: "Be a Realist. Demand the Impossible."

Political analysts agree with that last statement, saying Bukovsky has no chance of winning the election. Lev Gudkov, director of the Levada Center polling agency, said Bukovsky did not even appear as a candidate in surveys.

"Kasyanov is much better known," Gudkov said, adding that the former prime minister had received a popularity rating of 0.5 percent in a recent survey. "He has no access to the Russian public. Nobody knows him."

Indeed, when bookmakers recently made a list of candidates, first lady Lyudmila Putina was on the list with 200-1 odds, but Bukovsky was nowhere to be seen.

"He is an anti-communist hero, and like many heroes, he is a little bit crazy," said Sergei Markov, a Kremlin-connected political analyst. "He continues to fight against communism even though communism disappeared 20 years ago. He is like Don Quixote."

He said Bukovsky would fail to get on the ballot due to a lack of financial backing and a complete absence of support from voters. Candidates unaffiliated with political parties need to collect 2 million signatures to be placed on the ballot.

Bukovsky said he would rely on volunteers and donations for his campaign and that he would not pay for signatures, a standard practice in Russian elections.

As Bukovsky chain-smoked throughout a 90-minute interview, his hands shook and his rheumy eyes showed that he was not a well man. He conceded that he did not have the strength for an active campaign and would not travel all over the country.

There is no doubt about his opposition, though. Even when talking about life in Britain, he remains stubbornly opposed to many issues, the eternal dissident.

He is a patron of the United Kingdom Independence Party, a marginal party that vehemently opposes British membership in the European Union and has published pamphlets and lectured on the "EUSSR," as he likes to call the EU.

"The EU structure is a pale copy of the Soviet Union, a huge bureaucratic unaccountable structure, a monster that strives to stifle any initiative," he said. "It costs a lot of money and will ruin the economies of the European countries pretty soon."

His other favorite bugbear is the television license that, by law, everyone has to pay for the upkeep of the BBC television channels. Bukovsky cut up an enlarged copy of his license outside the BBC headquarters as part of a campaign against a corporation that he says is politically biased.

Even though he knows his chances of getting on the ballot are slim and even slimmer of winning, he clearly enjoys thinking about how he might -- just might -- have a shot at the Kremlin.

"They might get themselves into big trouble with this idea of faking [elections]," he said, talking about a possible face-off between two Kremlin-backed candidates.

"Democracy could backfire on them. They split their vote, and if I come in the middle of it, we could all can end up with about 30 percent," he said, laughing before taking another puff on his cigarette.

Editor's note: This is the second in a series of profiles of possible presidential candidates.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.