Exactly a quarter-century ago, in the twilight of the Soviet Union, a literary development took place that only a few years earlier would have been utterly unthinkable: James Joyce's modernist masterpiece "Ulysses" was published in Russian.

The man who dared to take on Joyce, whose writing had been condemned in the Soviet Union back in 1934, was not a professional translator, but a physicist and philosopher. Furthermore, Sergei Khoruzhy, now 73, said he never expected to even read the weighty experimental tome, never mind become the first person to translate it into Russian.

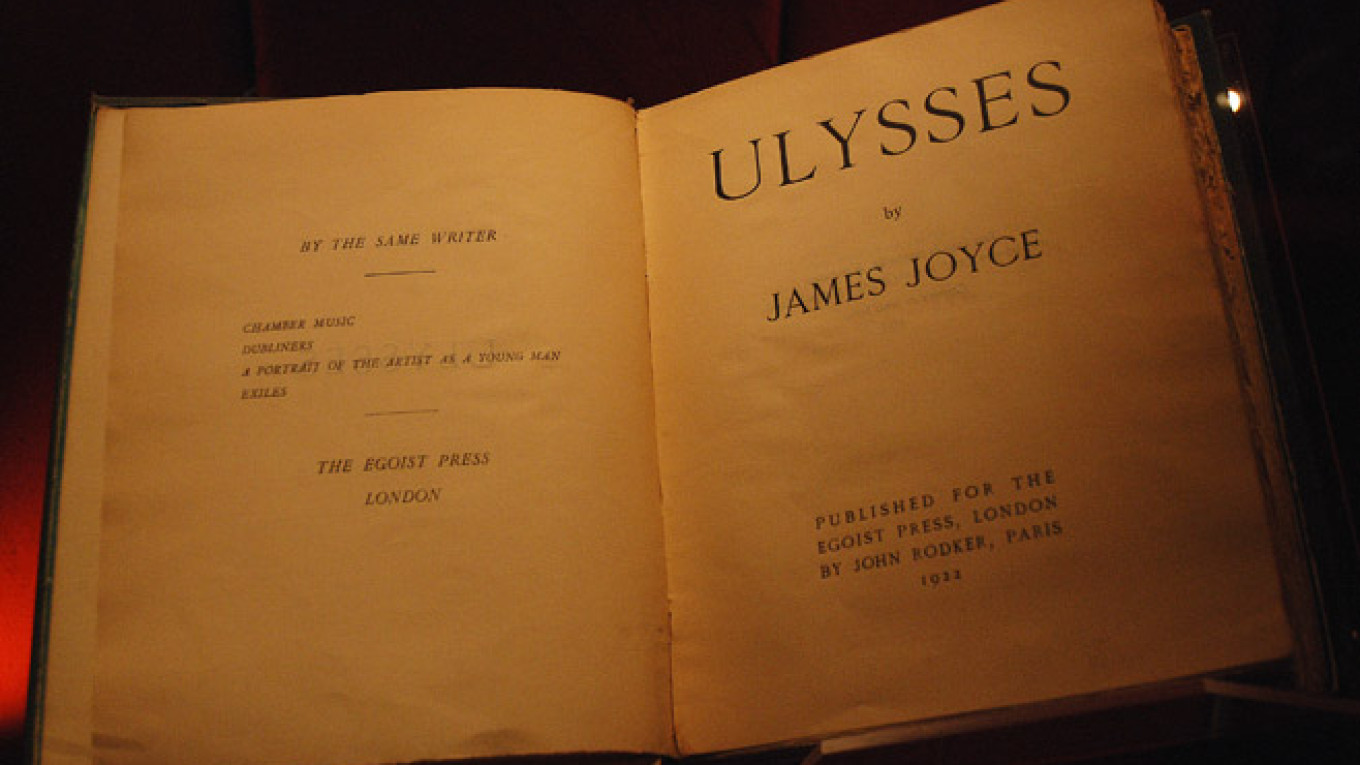

The achievement started out as a favor, albeit a rather big one. Khoruzhy's friend Viktor Khinkis was a well-known Russian translator who had been working on translating the book in secret for over a decade when he died in 1981. The novel, first published in entirety in 1922 and broadly acknowledged to be one of the most important novels of the 20th century, was banned in the Soviet Union for not conforming to the policy of socialist realism. When his health began to fail, Khinkis, who suffered from manic depression, asked Khoruzhy to help him finish the work.

"He realized he would not complete it in his lifetime, and he trusted me to help him," Khoruzhy said.

Khoruzhy was an unlikely choice, because he had no translation experience. "Actually, I disliked translations," he said. "I felt they were artificial in their language and style, and to be quite honest, I did not consider the profession of translator as something very creative. Viktor and I did not really involve each other in our work."

Working with his friend's manuscript and notes, Khoruzhy at first struggled to edit and revise.

"I tried to continue his work and I saw that it was impossible," he said. "And I started to just begin from scratch and produced my own translation. But I put his name on my work — both of our names — because without him this would not have happened."

A Hazardous Occupation

Translating "Ulysses" was an ambitious and even dangerous undertaking. Initially there was very little chance for publication, and for Khinkis, as for any intellectual who disagreed with the official ideological point of view, the secret police were a constant concern.

"Making a citizen incessantly think about [arrest] and wait for it is also a super way of shortening his days," wrote Khoruzhy in the "James Joyce Annual" in 1998.

"In fairness, a few years of Vic's stolen life should be added to the list of the heroic feats of our political police and guardians of the ideological front."

Both men were nonetheless dedicated to the work.

"It was important for Viktor because 'Ulysses' was the No. 1 most important work of literature in the English language that had not been translated into Russian," Khoruzhy said.

"It was forbidden literature and there were few if any chances for publication. It was a sort of hopeless adventure. He was ready to sacrifice so much for this enterprise."

As for Khoruzhy, his motivation was his loyalty to his friend. "I got into this business for one reason," he said. "He asked me to do it and he died."

My New Friend Joyce

After Khinkis' death, Khoruzhy began to immerse himself in Joyce.

"There were no specialists on Joyce in our universities — not in the whole country," he says. "It was part of a general cultural situation in the U.S.S.R. There were big sections of the humanities that were forbidden and extremely underdeveloped."

He approached the work philosophically. "I reflected a lot on Joyce and had my own ideas, my own conceptions of him and his works," he says. "I went quite profoundly into Joyce's personality. I felt personally connected with him. James Joyce remains my close friend."

Khoruzhy recalled "change on an all-Russia scale" in the mid-'80s as perestroika took hold, and in 1985 he received a contract for the publication of his manuscript. But his work was put through a rigid review process, as was standard at the time, and he was devastated by the results.

A page from each of the 18 episodes of the book was selected and scrutinized, and from this an average of errors was reached: seven per page, adding up to more than 7,000 in the whole text. The review — a 52-page document — was loaded with "lies of all kinds, direct and impudent," according to Khoruzhy, something he chalks up to the reviewer's incomprehension of the text.

"Joyce is a special world and a special profession," Khoruzhy says. "Quite different from that of a translator of English novels."

The Outsider

The Russian translation world questioned his qualifications and some suspected that the final product was the work of Khinkis alone.

"It was quite clear: I did not belong to the translation world, to their professional milieu," Khoruzhy recalled. "This completely unknown person, not a professional translator, presented not only a translation but the translation of one of the most important books in all of world literature. Of course it was a complete scandal. They could not accept it."

To keep the project alive, Khoruzhy had to agree to a significantly revised version. The book was delayed while editors analyzed the quality of the translation. In the meantime, in 1989, the manuscript was finally published in a serialized form in the journal "Foreign Literature," but this version, according to Khoruzhy, was "spoiled" by a preface and commentary prepared without his approval or knowledge.

In a letter to the journal's publisher, Khoruzhy wrote that, "as a professional philosopher and specialist in Joyce's work," it was his "natural right to complete the work, providing it with a preface and commentary of his own."

In 1993, he finally got his wish. "I consider the book edition to be the first official translation of 'Ulysses' in Russian," said Khoruzhy.

Literary Sensation

It was a great success. The first print run of 50,000 copies was almost immediately followed by 100,000 more.

"A bookseller in Moscow told me that this first book edition of 'Ulysses' was the most remarkable event in his very long career," Khoruzhy said. "He had to get a special worker whose job was, eight hours a day, to handle the copies of the books that would be sold. There were enormous queues in all the stores."

The translation remains the only Russian-language version of "Ulysses" available and was reprinted as recently as this year.

Lyudmila Voitkovska, a professor of linguistics and literature at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, heralded the Russian publication of "Ulysses" as proof that "glasnost had won."

Khoruzhy is less romantic about the circumstances in 1989.

"It was simply a product of the collapse of Soviet totalitarianism," he said. "In fact, there were no noticeable victories of progressive or dissident movements or any positive forces, it was just the collapse of the regime. We did not win anything by our own forces."

And if the appearance of "Ulysses" in Russian seemed to some to indicate the opening up of the former Soviet Union, its translator was damning of the picture today.

"It is obvious, everyone can see that we are moving backward," Khoruzhy said. "The Soviet period, its values and goals, are quite openly announced now as still valid. We are practically back in the U.S.S.R."

See also:

Inside the Soviet Union's Secret Erotica Collection

Contact the author at newsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.