Deputy Prosecutor General Nikolai Shepel, who reversed his earlier statements by making the admission last week, adamantly insisted, however, that the Shmel flamethrowers could not have sparked the inferno during a special forces operation to free the 1,200 hostages on Sept. 3. More than 330 people died in the Sept. 1-3 attack, about half of them children.

If prosecutors find that the commandos intentionally ignited the gym, as some Beslan residents and a regional lawmaker believe, it would mean that Russia violated an international convention banning the use of incendiary weapons that might injure or kill civilians, said Alexander Cherkasov, a senior member of the Memorial human rights group. Prosecutors also would then face the potentially unpleasant prospect of having to open an investigation into the military and security officials who organized the rescue operation, he said.

Although classified as a flamethrower, the Shmel in fact launches rocket-propelled projectiles, according to Jane's Information Group, an international center for defense information. The Shmel has three modifications: the RPO-A, whose shells explode; the RPO-Z, whose shells are incendiary; and the RPO-D, whose shells create smoke.

The commandos used the RPO-A type, Shepel told reporters on July 12. Its shells contain fuel-air explosives that on detonation form a ball of fire, creating a powerful blast effect.

Shepel said the fire lasts only a split second, while exposure of three to five seconds is required to inflict burns on a person or set fire to a building. "I am saying it once again: They don't have an incendiary effect," he said.

Military experts fired an RPO-A shell at dry, wooden building in a reconstruction of what happened in Beslan, he said. The force of the impact destroyed the building but the building did not catch fire, he said.

However, Alexander Pashin, an independent arms analyst, said that any type of explosive could create a fire.

Shepel initially said in November that it was the hostage-takers who had used flamethrowers, Novaya Gazeta reported Monday.

Prosecutors began investigating whether commandos had fired flamethrowers only after Beslan residents handed them used flamethrower barrels that they found around the school. Coding on the barrels was sufficient evidence to trace the barrels to their users.

Despite Shepel's denial last week, speculation persists that troops used the incendiary PRO-Z shells. Those shells contain napalm and leave traces of luminescent phosphorus on the site of detonation, Novaya Gazeta said.

Stanislav Kesayev, the head of a commission that is investigating the school seizure for the North Ossetia regional administration, said that preliminary results of a medical study found traces of phosphorus on the bodies.

Moreover, Beslan residents said the ruins of the gym glowed at night for weeks after the end of the hostage standoff, Novaya Gazeta said.

Beslan residents attending the ongoing trial of the only suspected surviving hostage-taker in the North Ossetian Supreme Court in Vladikavkaz said they had not noticed any glowing but were convinced that the commandos had caused the fire. Aza Gumesova, whose child died in the gym, said the fire was so hot that the metal crowns on her child's teeth melted.

A federal parliamentary commission headed by Federation Council Deputy Speaker Alexander Torshin is investigating what happened at Beslan. State Duma Speaker Boris Gryzlov said in early July that the commission would present its findings in September, but Torshin is still not ready to set a date. He said the commission needed to study the ongoing trial of the suspected hostage-taker, Nurpasha Kulayev. Torshin did not have any comment about Shepel's remarks, his spokeswoman, Valeria Shatunova, said Tuesday.

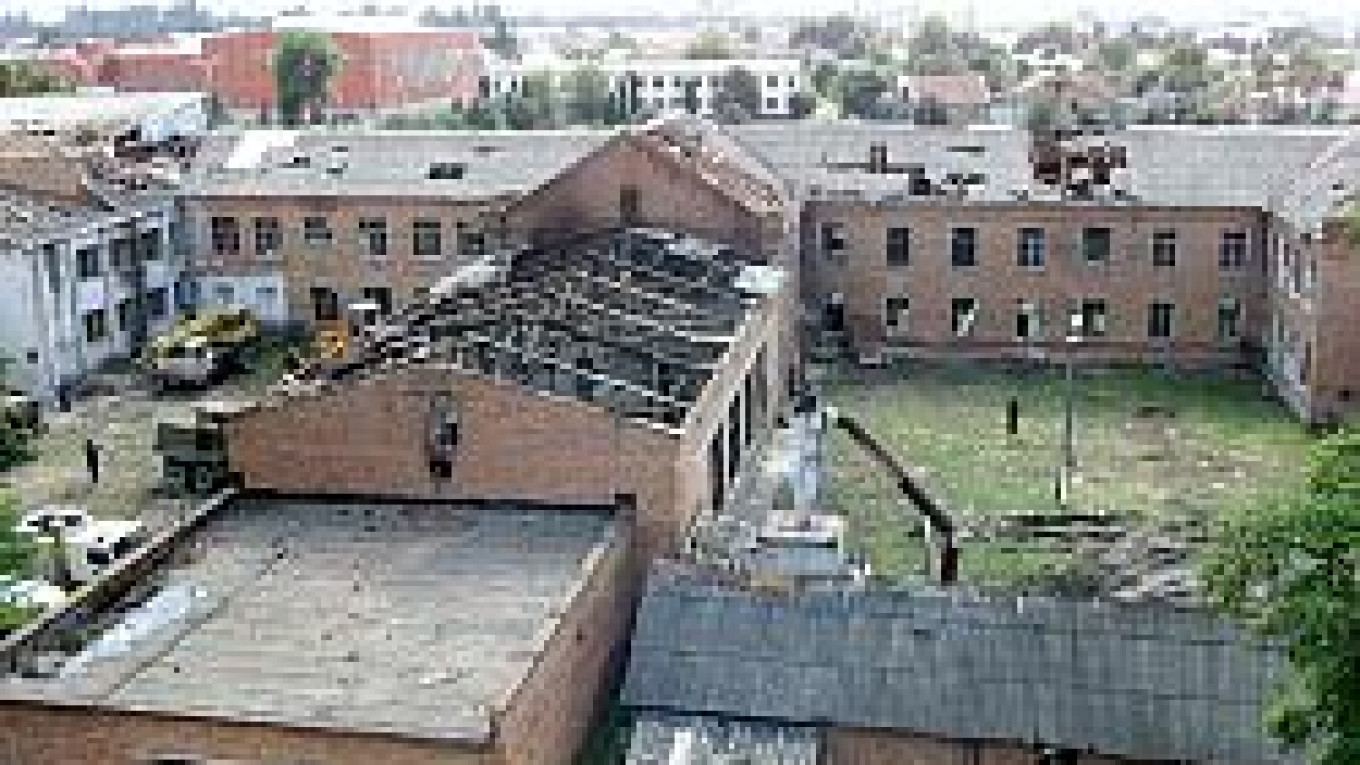

The blaze might have led to the collapse of the roof over the school's gym, burying many hostages, said Cherkasov, the Memorial activist. "It was difficult for the seriously injured people to get out. The ones who were trapped under the roof couldn't get out, and they continued to burn," he said. "If it hadn't been for the fire, many people could have gotten out and been saved."

www.vk.mesi.ru The Shmel, classified as a flamethrower, fires rocket-propelled projectiles. | |

Areas of the school where the terrorists holed up also suffered great destruction, suggesting that commandos might have aimed the flamethrowers only there, Cherkasov said.

But if the blame falls on the commandos, rights activists will demand that they act more discriminately in possible future hostage crises, Cherkasov said.

Pashin, the arms analyst, said the commandos were professionals who would have carefully chosen their weapons and refrained from firing indiscriminately if there had been a risk of civilian casualties.

Shepel also said the military experts' test "sweeps away all talk that the weapons that were used are banned ... by international agreements and conventions."

The 1980 Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons Which May Be Deemed to Be Excessively Injurious or to Have Indiscriminate Effects, of which Russia is a signatory, bans or restricts the use of certain weapons that are deemed particularly cruel. Protocol 3 of the convention bans the targeting of civilians with incendiary weapons and restricts the use of air-delivered incendiary weapons against military targets that are close to groups of civilians.

The convention lacks verification and enforcement mechanisms, and it does not spell out any formal process for resolving compliance concerns. Initially, the convention covered only international armed conflicts, but signatories extended it to apply to internal conflicts in 2001.

Staff Writer Anatoly Medetsky reported from Moscow.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.