The champagne corks were already popping for New Year's Eve celebrations when several thousand Crimeans received an unexpected phone call.

The voice on the end of the phone was a pollster from the Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM).

The pollster had just two questions:"Do you or do you not support the signing of a contract with Ukraine for the supply of electricity to Crimea if it describes Crimea as part of Ukraine?" And: "Are you willing to endure temporary difficulties caused by minor disruptions of power supplies in the coming 3-4 months?"

As was announced on state television, the poll had been conducted on the urgent orders of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Crimea had by that point already experienced months of power shortages following the destruction of power lines from the Ukrainian mainland. Moscow was in talks with Kiev over a deal that would save Crimea from further blackouts.

But VTsIOM reported that 93 percent of Crimeans had rejected the deal to bring power back to their homes. Moreover, 94 percent said they would bear "temporary difficulties" rather than accept Kiev's demand to label Crimea — annexed by Russia in March 2014 — part of Ukraine.

With this widely advertised mandate in his back pocket, Putin turned his back on the negotiating table, and left Crimeans in the dark.

Russian state media unanimously portrayed the results of the VTsIOM poll as proof of Crimeans' loyalty towards Moscow. But many sociologists and commentators poured doubt on that conclusion, criticizing the poll's timing and methodology. First, it was conducted on what is arguably Russia's biggest national holiday, raising questions over the reliability (and sobriety) of the respondents. Second, the respondents had been interviewed by phone, causing confusion over whether pollsters had reached those actually experiencing power shortages.

Yet more worrying was the poll's leading phrasing, which, some said, showed that the questions could only have been penned verbatim by the Kremlin.

The head of the VTsIOM pollster Valery Fyodorov confirmed to The Moscow Times that they did not write the questions themselves. He also said VTsIOM had warned against the phrasing of the second question — "temporary difficulties" and "minor disruptions"— but that the feedback had been ignored.

But he defended his organization's work, saying that such conflicts of opinion were a "common occurrence with clients" and what mattered was not who ordered a poll, but how it was carried out.

Grigory Yudin, a sociologist at the Higher School of Economics, questioned whether a poll openly commissioned by Putin could ever produce reliable results. He said respondents were unlikely to be open in their replies if the subject of their criticism — the Kremlin — was also the party asking the question. "It's not only dangerous, it's generally useless," he said.

The image portrayed by state media of polls providing Russians with a direct hotline to the Kremlin for their everyday concerns is also skewed, he said. The Kremlin communicates top down, not bottom up.

Sociology or Propaganda?

Interpreting polls in Russia is often like battling a hydra: for every question answered, another two raise their head.

And yet knowing what people in Russia are really thinking is of crucial importance: for foreign media and officials who are trying to gauge popular support for Putin's rhetoric, for Kremlin critics who hope the numbers will back their cause, and for the Kremlin itself which, ahead of parliamentary elections this year and presidential elections in 2018, wants to nip public discontent in the bud.

Within a context where there are few other mechanisms of feedback in the form of free elections, free media and public protests, polls published by state-funded pollsters VTsIOM and the Public Opinion Foundation (FOM) as well as the independent Levada Center make weekly headlines.

"Polls have become the only way for [Russian] society to know itself," says sociologist Yudin.

Sociologists, pollsters and political analysts diverge in their views of what the polls actually mean. But they mostly agree that Russian polls cannot be taken at face value.

"Their task is simply to supply the informational background for a positive narrative [in support] of the authorities," says political analyst Gleb Pavlovsky.

No Hope

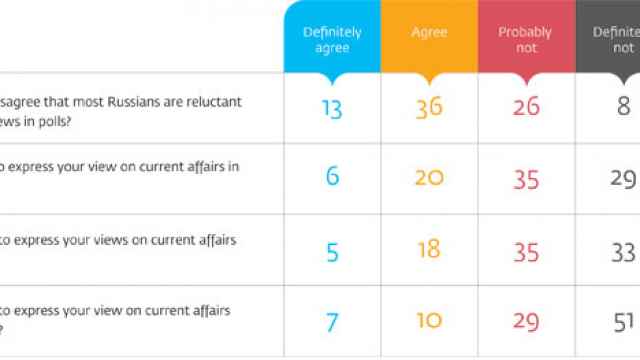

Russians need little prompting to remember a time when speaking openly could lead to decades in exile or in a labor camp. In a poll published in January by Levada, 26 percent of those questioned said they were reluctant to express their views in polls. Considering those who said so actually opened their doors to the pollsters anyway, the real figure of people who bite their tongue is probably higher.

Numbers in support of the Kremlin are widely publicized in state media, and herein lies another vulnerability, says political scientist Yekaterina Schulmann: "The Kremlin seeks an artificial overwhelming majority to intimidate dissenters into believing they are nothing but 'random error.'"

The effects of this are two-fold: As well as cajoling even more Russians into joining the pro-Putin camp, it could also make those who don't toe the Kremlin line less likely to open their doors to pollsters.

"During normal times, people who choose not to talk to pollsters do so because they don't feel like it or don't have the time. But in a period of 'political mobilization' the reason to actually respond becomes politically motivated," says analyst Kirill Rogov. That could further distort the results in Putin's favor.

Even Levada's work is in danger of being politicized following attempts to label the organization a "foreign agent" for receiving funding from abroad.

Though Levada has dodged the label as of yet, it has already led some regional authorities to cut off cooperation with the pollster, head of Levada Lev Gudkov said. Levada has also refused all foreign funding, further increasing the gap between the resources at its disposal and that of state-funded pollsters.

Doublethink

The argument that Russians are vulnerable to self-censorship leaves Gudkov, of Levada, unfazed.

"I really don't care what Ivan Ivanovich thinks in his kitchen while talking to his wife about Putin's politics or price increases. What is important is what he says in the public space," he said.

He believes that as long as factors such as the number of respondents remains more or less constant, polls carried out over time can still give meaningful ground for sociological analysis.

"Rather than trusting or distrusting poll numbers, it is important to understand what they actually mean. Now they measure the belief in Putin's ability to control the situation among those who respond," says sociologist Yudin.

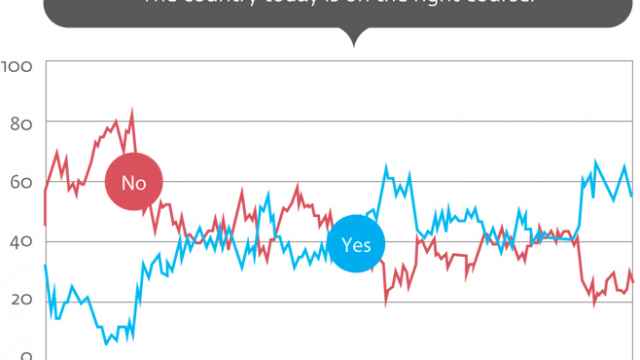

In the absence of competing sources of information, most Russians obtain their news through state television. On the surface, therefore, "public opinion" monitored in polls largely reflects the dominant Kremlin narrative.

But a closer look at poll results also shows respondents often give conflicting answers, a state of cognitive dissonance Gudkov labels "doublethink" — in reference to George Orwell's dystopian novel "1984" where people simultaneously hold two contrary beliefs.

Russians will, for example, simultaneously express large distrust of government officials — suspecting them of corruption and pursuing their own goals — or denounce specific policy decisions, such as the destruction of food banned for import in retaliation of Western sanctions, while continuing to pledge their support for the same government.

That demonstration of loyalty combined with high levels of distrust is a survival strategy reminiscent of Soviet times, says Gudkov: "We're recording a relapse to a Soviet-style totalitarian consciousness."

Teflon Putin?

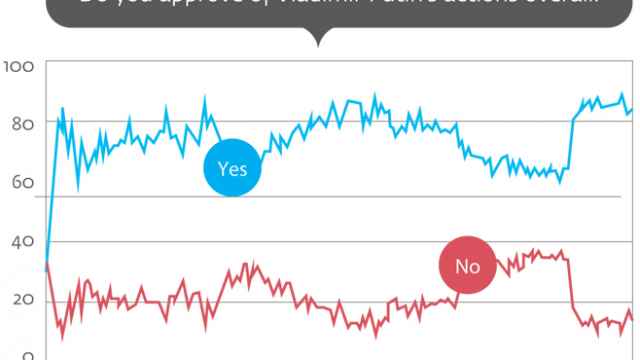

Polls show that reports of widespread corruption in Putin's inner circles have cemented widespread distrust of the government. Yet scandals such as those surrounding Russia's General Prosecutor Yury Chaika — incriminating his sons in a range of shady business deals — seem to be water off a duck's back for Putin's popularity ratings famously referred to in Russia as "the 86 percent."

In fact, though instability reigns in all other sectors of Russian life — economic crisis, terrorist threats, political standoffs, wars — Putin's ratings since Russia's annexation of Crimea have been a beacon of stability.

But it would be a mistake to conclude Russians ardently support the leader, says Gudkov, since a large segment of the population neither love Putin nor hate him: "As much as 65 percent say they have nothing bad to say about him, or say they only 'mostly' support him."

The dominant mood in Russia is cynical apathy. Respondents say neither Yes or No, but OK to most politically-themed questions, including those on their president.

Information Bubble

The effectiveness of state propaganda and the resulting uniformity among poll respondents is a double-edged sword for the Kremlin, says political analyst Schulmann. She said that having cracked down on civil society, the Russian leadership finds itself in an information bubble where it has no way to gauge its own population, except by "obsessing" over polls.

The Russian elite often falls victim to the same informational landscape as its subjects — forgetting that the propaganda snare was set up by its own officials. "[It is] a case of propaganda working inwards, a case of the poisoner inhaling his own poison," says Schulmann.

It is common knowledge that the Kremlin also monitors public opinion through its own secret polls. But the more skillful Russians become at doublethink, the less informative their answers can ever be — even in closed polls.

Former mayor Yury Luzhkov supposedly enjoyed widespread support among Muscovites, despite his alleged involvement in corruption scandals, until he was ousted from his post in 2010. Within weeks, his popularity plummeted. His roller coaster ratings showed how quickly Russians can abandon ship in order to stay in tune with the general party line.

Or, in the words of sociologist Yudin: “In a democracy, first the ratings go down, and then there is a change of power. In Russia, it is the opposite: if the ratings go down, it would mean that the power has already changed.”

Contact the author at e.hartog@imedia.ru. Follow the author on Twitter: @EvaHartog

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.